New Book Celebrates Trouser Press Music Mag’s 50th Anniversary

by Jeff Tamarkin Fifty years ago, a few Who fans in the New York area launched a zine called, at first, Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press in which they wrote about music that they liked, without regard for its commerciality. Much of that music was far removed from the mainstream—“alternative rock” before the phrase was even coined.

Fifty years ago, a few Who fans in the New York area launched a zine called, at first, Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press in which they wrote about music that they liked, without regard for its commerciality. Much of that music was far removed from the mainstream—“alternative rock” before the phrase was even coined.

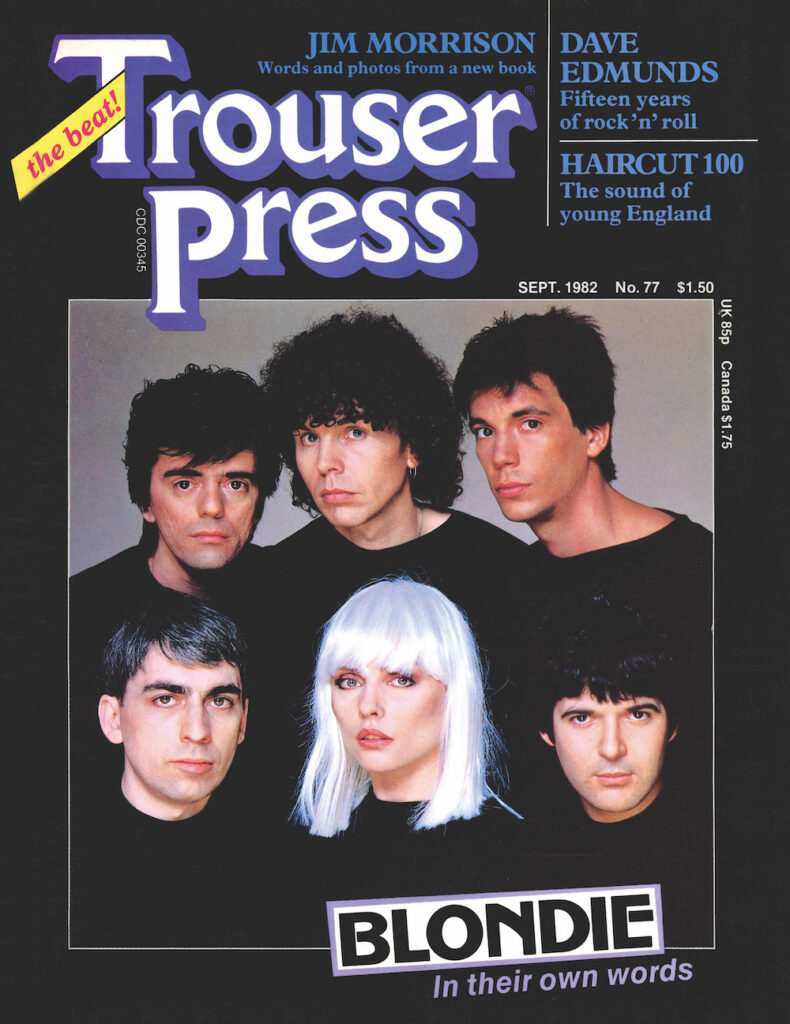

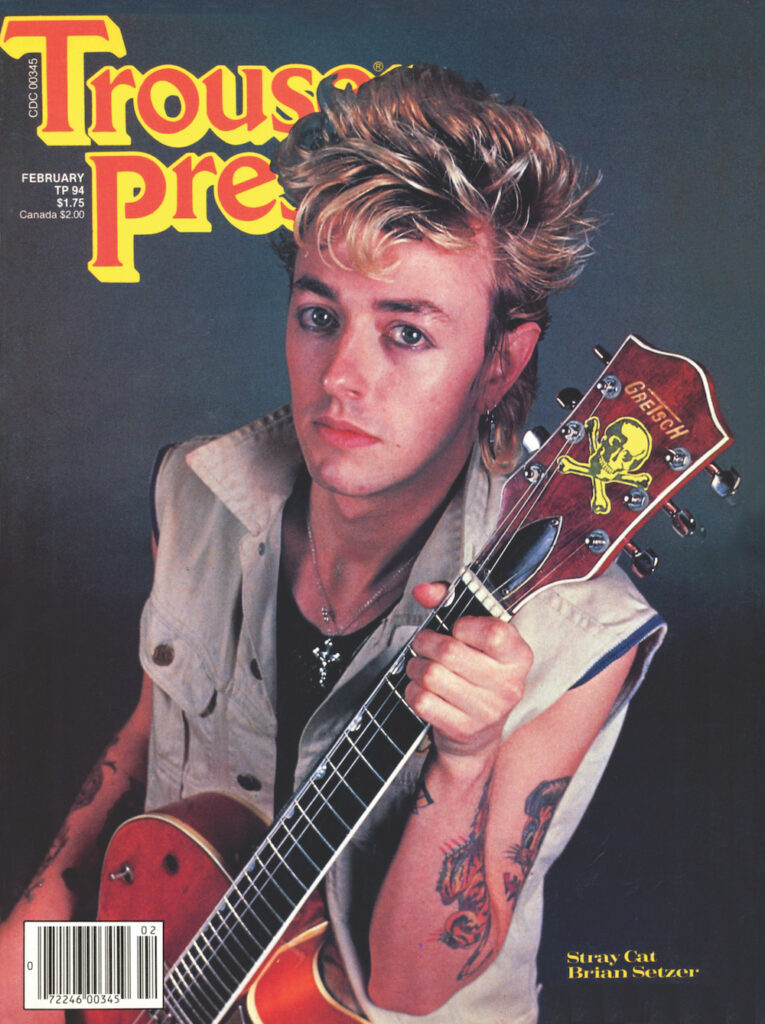

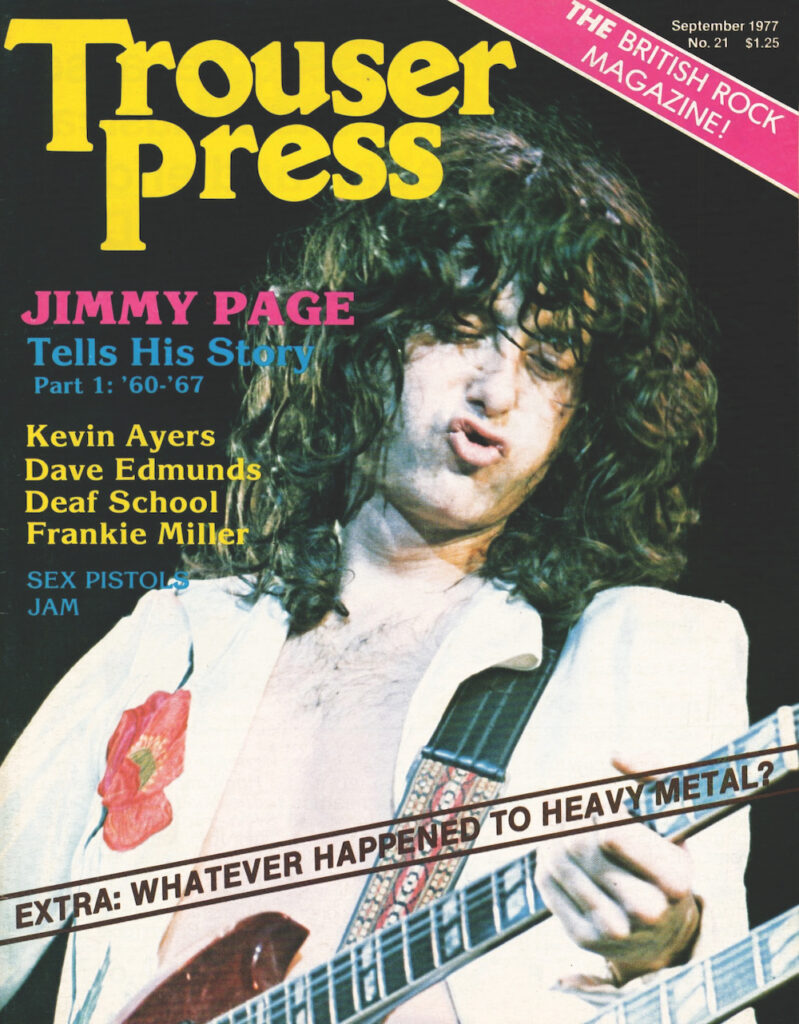

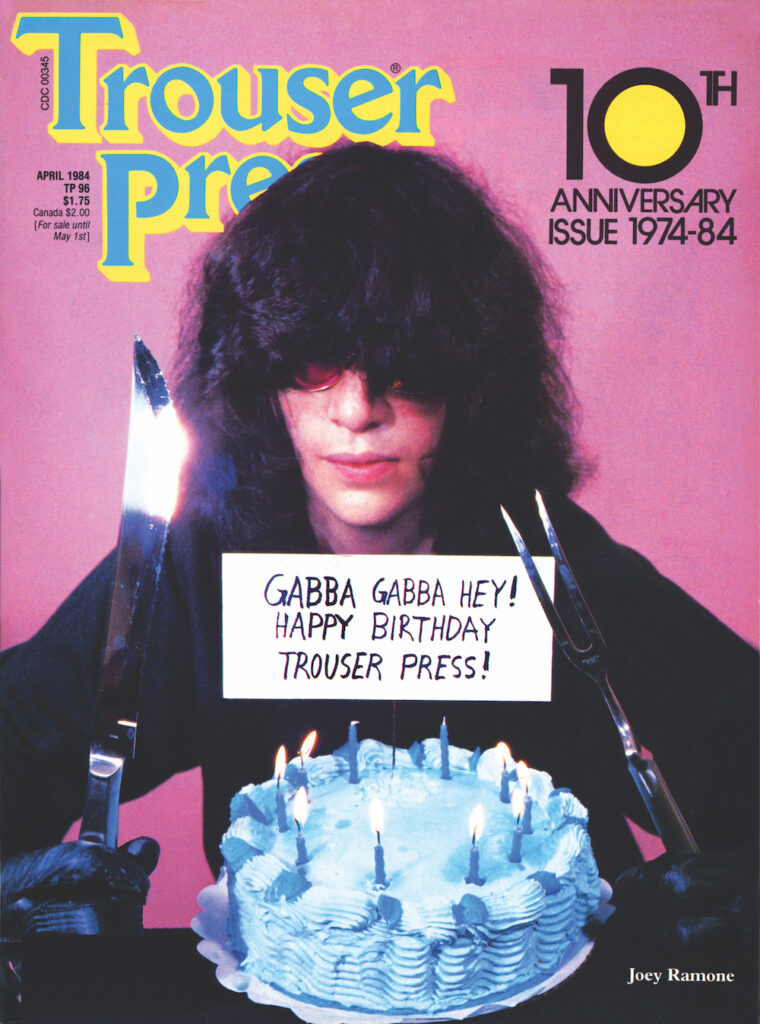

Over the next 10 years, with its title clipped to Trouser Press, the publication found a wider audience and expanded its coverage, without losing the attitude and enthusiasm that marked it from the start. Trouser Press published hundreds of articles, interviews and reviews, written by talented music journalists and accompanied by stunning original photographs. Then, in 1984, co-founder Ira Robbins pulled the plug.

Trouser Press as an entity outlived Trouser Press magazine, however, moving into the online world and into book publishing, first with a series of record guides and, more recently, titles delving into the music from various other angles. Now, Robbins has published Zip It Up! The Best of Trouser Press Magazine 1974-1984, a 440-page, large-format paperback featuring selections from the magazine on the 1960s, classic rock, glam rock, prog and art rock, reggae, the roots of punk, American punk and new wave, U.K. punk and new wave and post-punk.

Among the artists featured in the book: Small Faces, Jimmy Page, Pete Townshend, Todd Rundgren, Ray Davies, Cheap Trick, T. Rex, Lou Reed, Bryan Ferry, Genesis, Robert Fripp, Iggy Pop, Graham Parker, Television, the Ramones, Blondie, R.E.M., the Go-Go’s, the Clash, Sex Pistols, Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe, the Cure, U2, Joan Jett, Billy Idol and many others. [The book, published on March 14, 2024, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Best Classic Bands spoke with Robbins about the book and the role that Trouser Press played during its decade of covering some of the most exciting, innovative music ever made.

Best Classic Bands: How did you envision Trouser Press, and how did you get it off the ground?

Ira Robbins: It was, as I have been fond of saying, a whim whose time had come. Dave Schulps and I met at the Bronx High School of Science and bonded over our love of the Who and British rock in general. I was deep into radical politics and fairly uninterested in education, especially as it pertained to reading and writing (ironic, yes), and had a thought of earning a living as a radio engineer while I fought against the war in Vietnam.

We had a classmate, the legendary (and now late) character named Hank Frank, who got a record review published in Creem; that was a bit of inspiration. Dave and I both aspired to write about the music we loved, but never imagined that to be a career path. He went off to George Washington University (eventually studying journalism) and I stayed in New York, doing one year (on a full scholarship) in a two-year tech school and then transferring to Brooklyn Poly, where I finished a four-year degree in 1975.

Somehow, the idea of creating a fanzine in order to fulfill our otherwise frustrated dreams of publishing our writing emerged, and by the end of 1973, we had decided to try putting together an issue.

We saw ourselves as filling a niche of writing about (mostly British) bands that were not being covered in the American music media. We called ourselves in a pre-launch promo letter “the alternative to the alternative alternatives.”

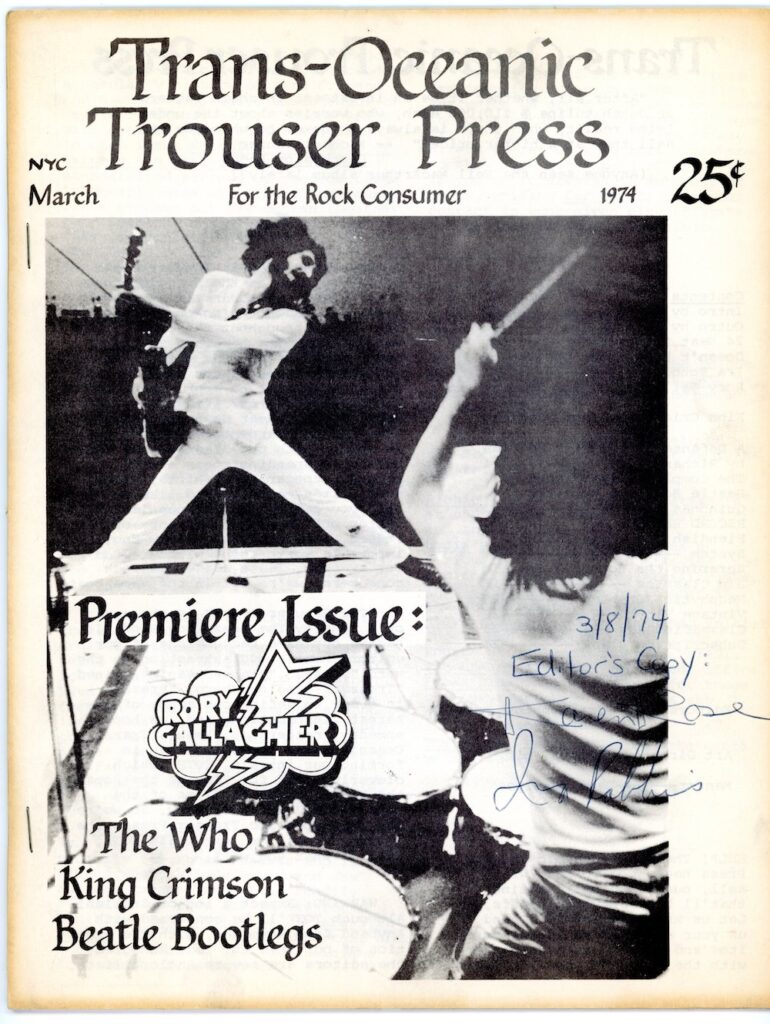

We didn’t really set out to be obscure, just to share our enthusiasm for artists without regard for their commercial success in the U.S. We initially gravitated to British Invasion acts as well as then-current rock artists from across the pond. Although we picked a confounding name for the magazine (Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press) by crossing a song by the Bonzo Dog Band with the Anglophiliac initials of the great British TV show Top of the Pops, we did have a clever guerrilla marketing plan: to write about artists we liked who had concerts coming up in New York and then selling issues in front of the venues. That was why, on March 9, 1974, the three of us stood in the rain outside the Academy of Music on 14th Street and flogged our 25-cent mimeographed fanzine to fans of the great Irish guitarist Rory Gallagher.

What was your journalistic inspiration? Were there other rock magazines that you looked to as good examples of what you wanted to do?

Dave and I were in thrall to Melody Maker and the other British music weeklies as well as Creem, Hit Parader, Crawdaddy, ZigZag, Let It Rock, Phonograph Record, Fusion, Zoo World (which I started writing for just before Trouser Press launched; I suppose a few months earlier and TP might not have seemed so vital an outlet to me) and the nascent world of American rock fanzines, especially Bomp! and The Rock Marketplace. We idolized the likes of Nik Cohn, Nick Kent, Lillian Roxon, Gloria Stavers, Richard Meltzer, Nick Tosches, Ken Barnes, Paul Williams, Pete Frame and others I’m not thinking of at the moment.

From the beginning, TP focused on certain types of music and bands at the exclusion of others. What made an artist/band TP-worthy and others not?

Not sure I can articulate that now, since at the time it was really a matter of our own oddball tastes. We weren’t editorially sophisticated enough to have a formal idea about what we were doing, but we had a lot of strong opinions about music and we let those guide us without much self-consciousness about serving a demographic or establishing an ethos. But somehow we managed to do that anyway. Setting aside my abiding enthusiasm for blues, old-timey folk and bluegrass (none of which we ever covered beyond a stray record review or two), we wrote about what we liked.

I personally loathed the Grateful Dead, Bruce Springsteen and what was then called Southern Rock, the Laurel Canyon singer-songwriter cadre, Top 40, funk, disco, etc.—and that had a lot to do with what wasn’t in the magazine. (When we did do a cover story about Bruce, we didn’t put his picture on the cover. I could only be so accommodating.) And although we wrote about American and European artists, we stuck to our guns about only putting U.K. acts on the cover until issue 30, when Todd Rundgren was our cover star. Our second cover slogan, unabashedly aping Creem’s, was “America’s Only British Rock Magazine.” A lot of people thought we were based in London because of that.

How did you find out about new music coming out of the U.K.?

The British weeklies were our lifeline, but an early alliance with a couple of record import companies—most notably Marty Scott’s JEM, who not only distributed TP to record stores but supplied us with records—was invaluable. We used to get the new release sheets they would send to stores and order whatever struck our fancy in exchange for advertising space. We had an album review section dedicated to imports and our singles column always covered U.K. releases as well. Most U.S. magazines considered imports out of bounds because they weren’t widely available, but we had no such reservations. (You may recall that the 1979 Rolling Stone Record Guide ignored imports as a rule.) At first it was a lot of prog, glam and U.K. oddballs like Deaf School, Doctors of Madness and Kevin Coyne, but later on, when punk hit, there was a stretch in ’77/’78 when every week would bring a box of 45s and LPs that we would play on the office stereo and be completely amazed at—Pistols, Clash, Gen X, Vibrators, Siouxsie, Sham, Buzzcocks, Damned, etc.

Listen to the Bonzo Dog Band track that inspired the magazine’s name

Did you know there would be an audience for the “smaller” bands, that there were other fans out there like yourselves?

Not a clue. We just didn’t think record sales or radio play had anything to do with artistic merit. We were anti-poptimist through and through, long before that was an articulated concept. Looking back over the issues, it seems as if we balanced that underdog/underground instinct in the reviews with a far more mainstream view in features. We were never really that adventurous with covers—i.e., featuring artists who were not widely known as, say, New York Rocker did—but inside we covered whatever we were excited about or what a writer we liked was excited about.

The Who were the quintessential Trouser Press band. What first attracted you to them? And did you have any encounters with Pete Townshend or any of the other band members?

My reasons for becoming a Who freak are as lost to me as my reasons for becoming a Yankee fan. In early 1968, I encountered The Who Sell Out (no recollection how) and saw Monterey Pop in a special early screening at Lincoln Center and my fandom was set for life. I’d been bowled over by the Beatles and the Stones as a 10-year-old, but four years later, the confused whirlwind of my adolescence found a home in the Who’s violence and irreverence and intelligence and sense of alienation. I was instantly attracted to the persona Pete Townshend projected. If you felt isolated, the Who offered a lifeline, an identity.

The Who were not a popular group in America at the time—in fact, they were considered fairly disreputable. That appealed to my appreciation for underdogs, and an elitist sense that joining (ahem) a little-loved band made you special and out of the ordinary. It was another element of the nonconformity that was important to my self-image. With the release of Tommy in 1969, they gained a whole new audience, which began the inevitable fan process of losing the imaginary sense of ownership of an obscure band to the wash of superstardom.

In the first issue of TOTP, I showed off what I imagined was my superior knowledge with an article not-so-grandly titled “24 Neat Things I Bet Somebody Doesn’t Know About the Who.” I mailed a copy of TOTP 1 to Townshend (every self-respecting Who freak knew his address) and got a two-page hand-written reply to the article that ended “Much love & respect to your fine paper.” I’ve had some odd and amusing encounters with him since then, but it was Dave who got to go to his house and do a lengthy interview.

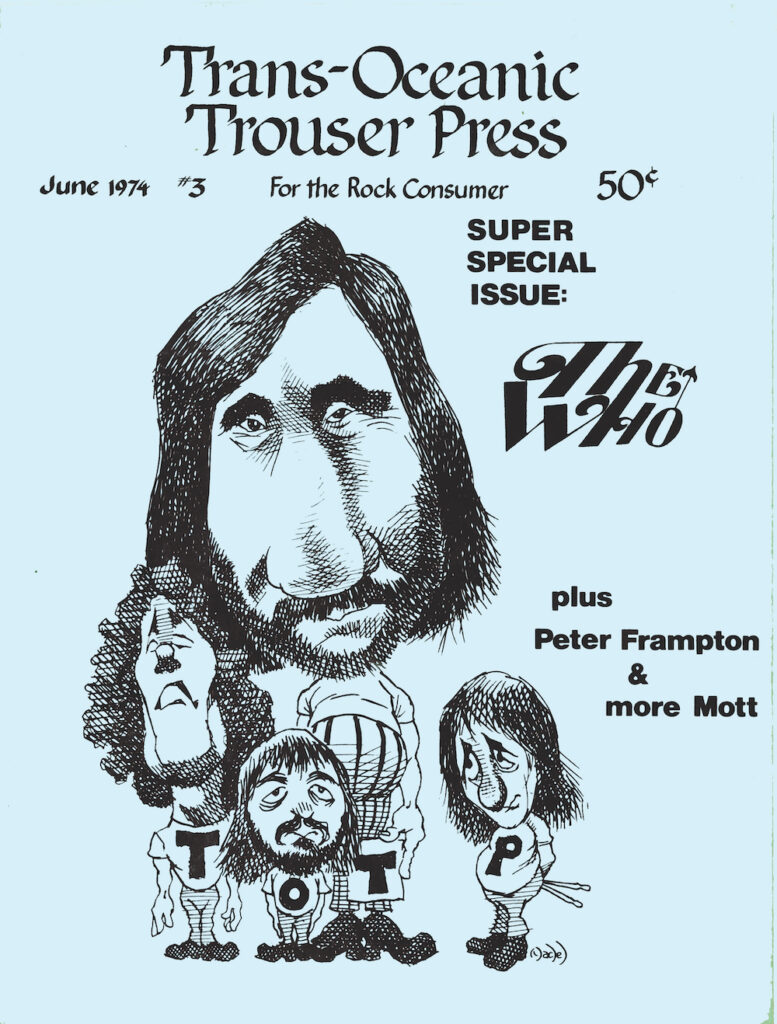

In June ’74, when the Who were in New York for four shows at Madison Square Garden, Dave and I bought drinks for Moon and Entwistle in the bar of their hotel and got their autographs on the cover of issue 3, which depicted them in a cartoon that neither liked.

Which other bands were “Trouser press bands”?

The Residents, Shoes, Blondie, Clash, Ramones, Elvis Costello, Devo, Genesis, Mott the Hoople, Sparks, Kinks, Roxy/Ferry/Eno, Fripp, Iggy, Lou Reed, Peter Gabriel, Nick Lowe. (As you can infer, women musicians were not amply represented in our pages. But as much as I wish it were otherwise, I don’t think we were any more deficient than other publications of the time.)

How did the arrival of punk affect TP’s outlook and coverage?

It felt like a rebirth to me and we joined the fun without so much as a second thought. New wave (and I mean that in the original umbrella sense, not the skinny tie and synths cliché it became) was a musical focus that perfectly suited my tastes and enthusiasms. The British bands were new, great and underexposed in America; at the same time, we had embraced the independent scenes of bands that had begun cropping up all around the U.S. a few years earlier, so we finally had an international equivalence we could be happy with. We didn’t handle the New York scene well at first because we felt our readers outside NY had no opportunity to hear the bands so we felt it elitist and futile to write about them, despite the fact that we were very keen on a lot of them.

It also helped that we managed to somehow attract two first-rate British writers, Paul Rambali and Pete Silverton, to cover the scene first-hand for us.

Related: In 2023, Trouser Press Books published the third title from Rhino Records co-founder Harold Bronson

What separated TP from, to give just a few examples, Rolling Stone, Creem, Hit Parader and all of the others? Was it an attitude, a style, the focus?

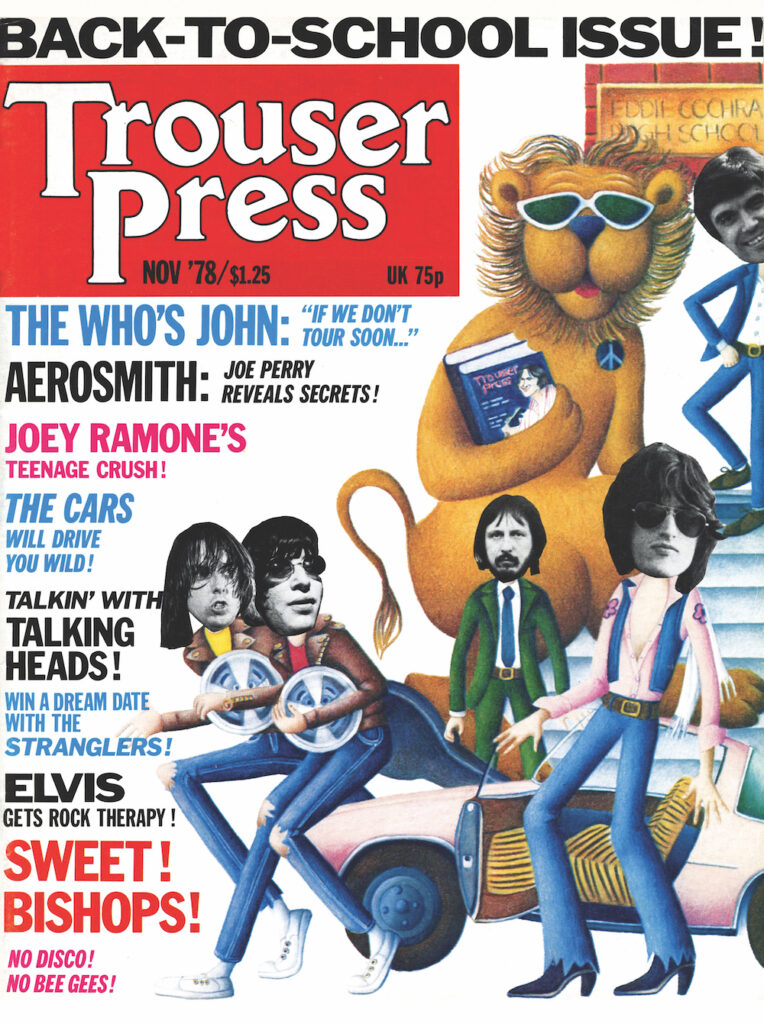

RS was commercially minded and mainstream minded (and not just on music): we stuck to our guns and covered whatever we wanted to. We always felt that our readers, whoever they were, should let us blaze a trail of our own making rather than pander to them, which we only began doing in the last few years, when the popularity of MTV bands (Duran Duran, Eurythmics, Culture Club, Cars, Adam Ant, Big Country, Soft Cell, etc.) became our way to sell more copies (and, for a while, stay in business).

I think we stayed more like Creem of the mid-‘70s until the end (meanwhile, they became more like Circus, with Kiss getting megagallons of ink): snarky, funny, unpredictable, a bit rash. But our art direction (credit Judy Sitz) was always tied to a more radical punk visual ethos.

And, add to all that, we were—thanks to the Bonzo Dog Band and Marcel Duchamp—devoted fans of Dada, and we retained a fondness for stray bits of silliness (like running random song lyrics or other nonsense on the contents page or as running feet throughout an issue.) I don’t know that any other rock magazine incorporated that influence as enthusiastically (if at all).

As the years went on and TP grew into a more professional publication, how (if at all) did your approach to editorial content change? You widened your area of coverage greatly (a Frank Zappa cover would not have been thinkable in the beginning). Was there blowback when you started expanding?

Not that I recall (blowback). Our readers—evidently an eclectic bunch who had been attracted to the magazine for divergent reasons—attacked us in the letters column for everything we did at one time or another. We got used to it.

In terms of editorial coverage, I think we saw our mission more broadly as time went on. But that had a lot to do with the obligation of filling the feature well of a monthly magazine—a challenge that grew proportionally with the size and frequency of TP—and that not being addressable only by bands we really cared about. (We did, after all, put Jefferson Airplane, who would not be on my list of 500 favorite bands, on one cover.) A lot of it was letting go of the preciousness that fanzine publishing entails and finding a new purpose with a more generous stylistic brief. Maybe one way to look at this is that after the early years defined us we had the confidence to go outside the mold without fear of overly damaging the sense people had of TP.

I also think we put a lot of faith in our regular (staff and freelance) writers, whose tastes (collectively) were a lot broader than mine. They pitched us and we found it either agreeable or necessary to say yes to things we might not have thought of ourselves. Occasionally, we spotted what felt like a gap in our coverage (reggae, hardcore, metal) and addressed that but never with full conviction. Another factor is that my role in TP became increasingly about business; while I retained tyrannical oversight (I’m kidding about the tyranny) over the contents of every issue, day-to-day editorial decisions were largely made by editor Scott Isler. I don’t think I made many article assignments and I didn’t do much writing outside of record reviews.

Let’s get to the book. You had 10 years’ worth of articles to choose from. What was your selection process?

I tried to keep it simple so that the rights and royalties situation wouldn’t become unmanageable (hence the blanket decision not to include photographs that ran in the magazine) but kept finding things that felt important to include, whether because the writing was especially noteworthy or because I wanted the writer represented in the book or because the artist needed to be in there.

There were a couple of articles I knew we needed to include, starting with Dave Schulps’ massive Jimmy Page and Pete Townshend interviews, his somewhat skeptical piece on Kiss, his [first American outlet] phoner with Elvis Costello, the Devo-meets-Burroughs Q&A, Kathy Miller’s Marc Bolan piece, my weird and not entirely convincing “death of new wave” essay, Jim Green’s Residents/Ralph Records piece and the making of Blondie’s Eat to the Beat, one of Pete Silverton’s Clash articles and a news report Scott Isler did about the legendary PiL show in NY. Also, Ihor Slabicky’s lengthy encounter with Robert Fripp. I would have liked to include Ben Richardson’s in-depth Yardbirds history, but I was unable to track him down to get permission.

Some of the best writers ever to write about the music got their start in TP. What made a TP writer and who were some of the journalists that came through the TP ranks that you feel helped give the magazine its voice?

That one’s kind of a mystery to me since I don’t think we gave it a lot of thought at the time. We looked at clips and considered pitches, but we were only able to pay so poorly that we were always in need of writers who could and would contribute without being paid professional rates. Somehow, that got us some seriously great people—Dave Fricke, Steven Grant, Pete Silverton, Paul Rambali, Janet Macoska, Karen Schlosberg, Bill Flanagan, John Leland, Moira McCormick, Marianne Meyer, Jim Farber, Todd Everett, Kurt Loder and many others, all of whom went on to careers in journalism. (FWIW, some of our interns went on to great accomplishments as well.) It must have been that the smart and talented ones had the instinct and the ambition to seek us out and make TP great; I don’t know that we can take credit for scouting unproven talent in more than a few cases.

At the same time, Dave, Jim Green, Scott Isler and I were untested amateurs at the outset and yet we all developed into seriously good (if I may so say) rock writers.

What were some of the challenges in researching and writing about music—especially music that was in many cases pretty obscure—in the pre-internet days?

This is something that I doubt anyone under the age of 50 can fully comprehend: there were a handful of books about rock, some magazines and record company press releases. No Wikipedia, no Spotify, no discogs.com, no Behind the Album TV documentaries, no shelf after shelf of deeply researched biographies. Dave and I did a thing in high school (his idea) where we looked at microfilm of Melody Maker going back to the ‘50s to assemble a list of British musicians and the bands they played in. That, weirdly enough, was a huge asset when they came over and we got to interview them (because few outlets were interested, our puniness was less of an obstacle), we could ask knowledgably about their history and that established our bona fides. You’ll have to ask Dave how he researched the Page interview. That one boggles the mind.

Why did you close the magazine when you did and have you ever thought of reviving it? Could it even work in today’s climate?

It was a combination of things: finances, personal lives, exhaustion and the fact that MTV had become something of a national rock radio station, playing the music that we could only write about. I felt as if (take your pick) our work was done [or] we’d been pushed off our turf by superior technology.

I was admittedly jealous when Spin came along the year after we stopped; if we’d had their funding and business acumen and resources, we could have gone on and perhaps had more of an impact. I used to joke (when I was a lot younger than now) that if anyone had a million dollars they wanted to put up to start a music magazine, I would relaunch Trouser Press. I wouldn’t do it now.

I’d like to think that if we had kept on, we’d have had a lot of the same attributes that made Pitchfork successful. We had the same intensity and independent spirit. (But I would never have condoned rating points (or stars or letter grades). If you want to know what a reviewer thinks of a record, read the effin review, don’t let a number or a letter suffice.)

Let me add that TP existed in an era without awareness of a lot of the sensible sensitivities that have become baked into music journalism. We did use a lot of women writers and photographers, but that was about as far as our inclusiveness beyond the rock journalism prototype went. We covered a wide range of music, but we had blind spots where more adventurous musical curiosity might have led us. Also, we were in an era when artists, even anti-status punks, were on the other side of a divide that gave us license to ignore their feelings when it came to writing about them. We said some seriously mean shit about some musicians, and I don’t think—in the social media world where fans take up the digital cudgel at the slightest slight—we would be so free with our opinions now.

What impact has TP had on the music journalism that followed it?

I’m really not sure. Nice of you to ask, but I’ve never really thought about it in those terms.

Basking in the glow of all the praise the book and recent 50th birthday fuss has engendered, I could say a lot, but I have no basis in fact for that other than people’s ridiculously generous compliments.

There have been a lot of rock magazines over the years, and many of them were really good. I never felt TP was unique—sure, it had a distinct character and made readers feel like they were part of something, but then I felt the same way about the New Musical Express and Creem. What I will say is that—and you can read this on the TrouserPress.com message board any day of the week, where the phrase “Trouser Press band” gets applied to artists who post-date the magazine—we stood up for something in music that has endured, an appreciation for art over commerce and achievement over popularity. I don’t know if that influenced music journalism, but it seems to have resonance among a certain world of music fans. On the other hand, I’ve had a handful of writers tell me that what we did helped shape their work, so that’s something tangible.

Watch musicians Mike Fornatale, Sal Maida and Dennis Diken cover the Flamin’ Groovies’ “Shake Some Action” at Trouser Press’ 50th anniversary party in NYC, March 2024

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.