Tom Werman Talks About His ’70s Rock Signings: Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, REO Speedwagon

by Greg Brodsky

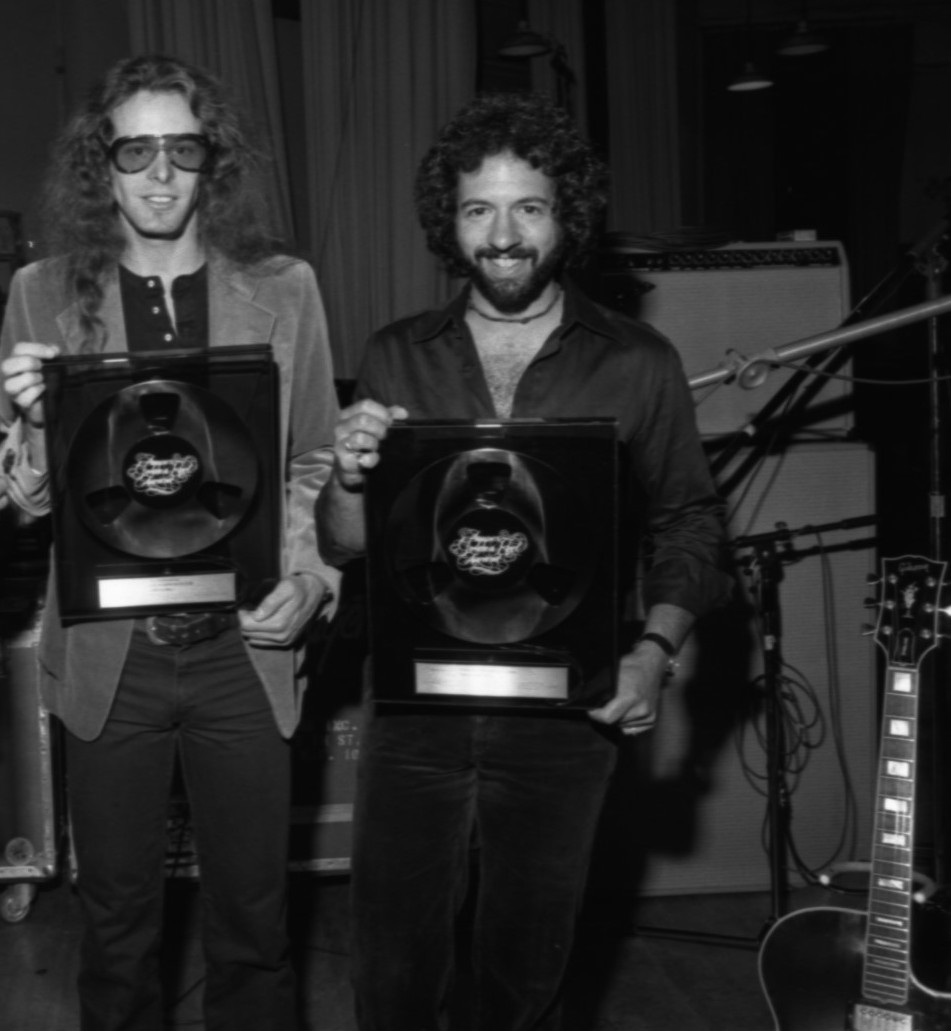

Ted Nugent (left) and Tom Werman display some of their Platinum hardware (Photo: Tom Werman Archives; used with permission)

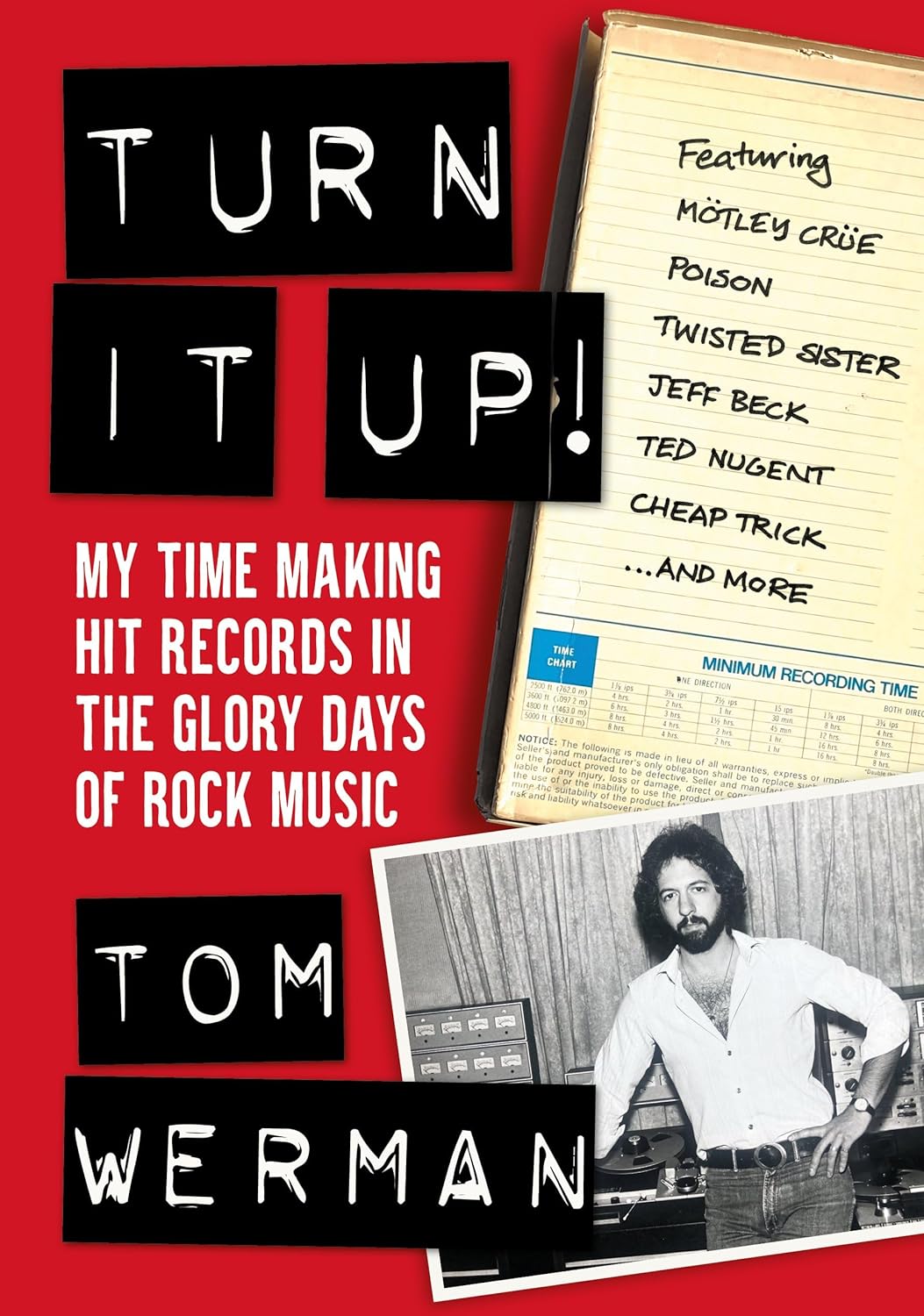

In a new book from longtime music industry executive Tom Werman, he writes about his days as a producer for some of the biggest recording artists of the ’70s and ’80s. Turn It Up!: My Time Making Hit Records In the Glory Days of Rock Music (Featuring Mötley Crüe, Poison, Twisted Sister, Jeff Beck, Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, And More) arrived November 21, 2023, via Jawbone Press. Werman spent the first 12 years of his career at CBS Records (now Sony Music), working for its Epic label. Following his significant success as an executive in the Artists and Repertoire (A&R) department, he moved on to become a much-sought after independent producer. Between the two phases of his career, he produced or co-produced 52 classic rock albums. Werman’s record-making résumé includes 23 Platinum- or Gold-selling albums and cumulative sales of more than 52 million copies. Best Classic Bands spoke to Werman, now 78, by phone recently; this first of two parts covers his Epic years.

Best Classic Bands: You’ve been retired from the music business for quite a while. I know the book has been something you’ve been wanting to do for a while. What finally got you going?

Tom Werman: It was the realization that there was a growing audience for classic rock, an audience that was interested in the music of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. Unlike my generation, who were only a little bit interested in our parents’ music… our children know everything about our music. That’s what drove me to say, ‘People are interested in this stuff,’ and I love reminiscing. I didn’t just waltz into the music business. It was a painful transition from something I hated and I got really lucky, and how I got into the studio and with whom I got into the studio. Just the timing of it all and how music was exploding then.

BCB: What were you doing and how did you get the meeting with Clive Davis, who ran CBS Records?

TW: I graduated from business school in 1969 and I was working for Grey Advertising in the account group. And I hated it. I initially turned down CBS Records because they didn’t pay as much! I was on a detergent account and then the Jif peanut butter account. We would go out to Cincinnati to Procter & Gamble to meet with the client and I wasn’t a very happy guy. And I didn’t feel that I was contributing much either. I just wasn’t excited about my life.

So, in 1970 I wrote Clive a letter: “Here’s who I am. I happen to have an MBA from Columbia. I love rock ’n’ roll, I’m a musician. I think I’d be much happier and productive with you.” And so they started interviewing me. Clive gave the letter to Walter Dean, the head of Business Affairs, and he gave it to [then-VP Marketing and future company President] Bruce Lundvall and I started interviewing. After around three months, Walter contacted me and said, “If you’re still interested in CBS, give me a call.” And he said, “I think you should meet with Clive.” In those days, meeting with Clive Davis was like a seminary student scoring an audience with the Pope. And that was it! He offered me a job on the spot when we met. It changed my life overnight.

So, in 1970 I wrote Clive a letter: “Here’s who I am. I happen to have an MBA from Columbia. I love rock ’n’ roll, I’m a musician. I think I’d be much happier and productive with you.” And so they started interviewing me. Clive gave the letter to Walter Dean, the head of Business Affairs, and he gave it to [then-VP Marketing and future company President] Bruce Lundvall and I started interviewing. After around three months, Walter contacted me and said, “If you’re still interested in CBS, give me a call.” And he said, “I think you should meet with Clive.” In those days, meeting with Clive Davis was like a seminary student scoring an audience with the Pope. And that was it! He offered me a job on the spot when we met. It changed my life overnight.

BCB: Your book notes that the company’s much bigger label, Columbia, had no positions available in A&R at that time.

TW: Epic Records at the time was so insignificant. The head of A&R was only a Director. In the corporate ladder, that’s not that big. I was the assistant to the Director. There were four A&R people, a small roster with some really old names plus Jeff Beck, the Yardbirds and Sly and the Family Stone. So we set about to build the roster. And we did. We seriously built the roster. We were selling something like $12 million when I came in [in 1970]. By the time I left [in 1982] it was $240 million.

BCB: You discovered some legendary bands early on, including an early incarnation of KISS and Rush. But neither signed with Epic. What happened?

TW: I heard a tape from a band called Wicked Lester and they were a pop group with around six guys. This independent producer was finishing their record. He had done it on his own dime. He came to us and I went down to the studio several times [Electric Lady] with Gene [Simmons] and Paul [Stanley] and the group. And it was very pop, very sweet. And we agreed to finish the record but they broke up before we could release. It was finished but we didn’t have a band to go on the road so we just kind of put it away. Either Gene or Paul called me some months later and said, “We’ve got a group and we’d like you to come hear us at this rehearsal studio.” So I took my boss and went to the rehearsal studio. It was a very early Kiss performance, white face, black tights, platform boots. Kind of performance art. When we got back to the sidewalk my boss said, “What the f*ck was that?” And I knew he didn’t get it. He was a smart guy but didn’t understand rock and roll and its appeal and how big an audience it could have. So he passed and he also passed on [Lynyrd] Skynyrd and he also passed on Rush. Rush not musically but because of corporate guidelines for advances. They wanted a $75,000 advance for two albums and in those days it was too much.

REO Speedwagon was my first signing. I flew out to Champaign, Illinois, and was met by Irving [Azoff, the veteran artist manager and music industry executive who managed the band early in his career] who took me to the Red Lion Inn that night, where the band blew the roof off. That turned out to be a good one.

Since I never produced them, my exposure to the individual members was limited. I wish I could have spent more time with the band, since they were funny and intelligent.

BCB: They released an album a year throughout the ’70s but they were no overnight sensations. Were you concerned?

TW: By that time my boss had left and was replaced by another one who wondered what I had been doing for six years. He said, “Are you interested in anybody right now and”” I said, “Yes, Ted Nugent.”

So I started going into the studio with Ted and became a producer. Bingo! Just like that. And that was it… we were off to the races. Then Molly Hatchet. And I co-signed Boston with Lennie Petze. And I left CBS. They wouldn’t give me a raise.

BCB: You skipped a little bit there. (Werman laughs) Ted was the first artist you produced?

TW: Yeah, we did five Platinum records together [including Cat Scratch Fever and Double Live Gonzo!, both triple-Platinum] and I’m still struggling to explain to people why I’m associated with Ted Nugent because he is so politically… [voice trails off]. He wasn’t the Ted that he is now. In the book, I explain his character and his integrity and his talent. I’ve got liberal friends who ask, “How can you even talk to him?” I say, “We have a personal relationship. We never discuss politics.” I don’t love what he says by any stretch. I think it’s terrible. He knows I’m a liberal Democrat.

BCB: Not long after you signed Nugent, another Midwestern band came to your attention.

TW: [Producer] Jack Douglas called me and said, “I saw a band that I think you should see.” I flew to Quincy, Illinois, with their manager, Ken Adamany, and saw them in this club. Catacombs. They were really, really loud… I even had to step outside for a while to be able to hear the songs more clearly, but I was really taken with them, and when I went home I told my boss he had to see them.

BCB: Ah, Cheap Trick!

TW: After I produced their second album, In Color, I worked with them in L.A. because they wanted to go there and said, “Whoa, I could live here!” I learned that the whole town was built to set up the entertainment industry. It wasn’t like that in New York where studios were crammed and dark. In L.A., they were fantastic. I told Epic I’d be much happier living in L.A. and could make better records. That was 1978 and my family moved to Laurel Canyon and we were there for 23 years.

BCB: That same year you produced Heaven Tonight, which gave us “Surrender.”

TW: The basis of the [recording] came from me, from The Who’s “Baba O’Riley.” I just plain stole it. Pete Townshend was always my main musical inspiration.

They were so good in the studio, we were never pressed for time. Robin [Zander] could do two songs a day. He’s the best singer I ever worked with, by far. Fabulous pitch. A producer’s dream. I have the greatest respect and love for them. They were musicians’ musicians. It was the most fun I’ve ever had in the recording studio. They were so easy, it was so good. They were truly amazing. We would finish our basic tracks in several days. You get 12, 14 songs done in few days was unheard of then. Bun E. Carlos would finish and hang a sign on his snare drum that said, “Gone Fishing.” And he would go home. And we would see him for rehearsal, and then in the studio, and never again. He came in, did his thing, and left.

Tom Werman (back row, 2nd from L), with Cheap Trick’s Robin Zander, Tom Petersson, Rick Nielsen and Bun E. Carlos, and various Epic Records staff members (Photo: Tom Werman Archives; used with permission)

Related: More on Werman’s years producing Cheap Trick

After 1982, I left CBS and began the next chapter of my career as an independent producer.

I had the opportunity to thank Clive a couple of years ago. I was in Manhattan to see a play and he was attending the same play and on the way out I stopped him and reintroduced myself and said, “You changed my life” by hiring me. He was delighted. He pretended that he remembered me. (laughs) That was a huge turnaround for me.

Turn It Up!: My Time Making Hit Records In the Glory Days of Rock Music (Featuring Mötley Crüe, Poison, Twisted Sister, Jeff Beck, Ted Nugent, Cheap Trick, And More) is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI can identify the people in Tom’s photo — Jim Charne, Tom, Al DeMarino, members of CT (Robin, Tom, Rick, Bun); bottom row: Alan Ostroff, Ken Adamany (CT’s manager), Jim Jeffries.