Whatever Happened to Stephen Talbot, ‘Leave It to Beaver”s Gilbert? We Asked Him!

by Jeff TamarkinIt’s the early 1970s and the counterculture in America is in full bloom—protests against the Vietnam War are sprouting in every city, and the youth are angry. One young, long-haired man, Stephen Talbot, is leading a student strike and speaking at a rally at his college when he looks out at the audience and sees a sign: “Gee, Beav, I don’t know,” it says.

Talbot had been outed. Someone had figured out that, earlier in his life, the activist onstage had inhabited the role of Gilbert Bates on one of the most popular TV sitcoms of the late ’50s and early ’60s, Leave It to Beaver. The in-joke on the sign was meant to lampoon one of Gilbert’s trademark lines—Talbot’s character on the show had one main job, to get Beaver Cleaver in trouble while saving his own skin.

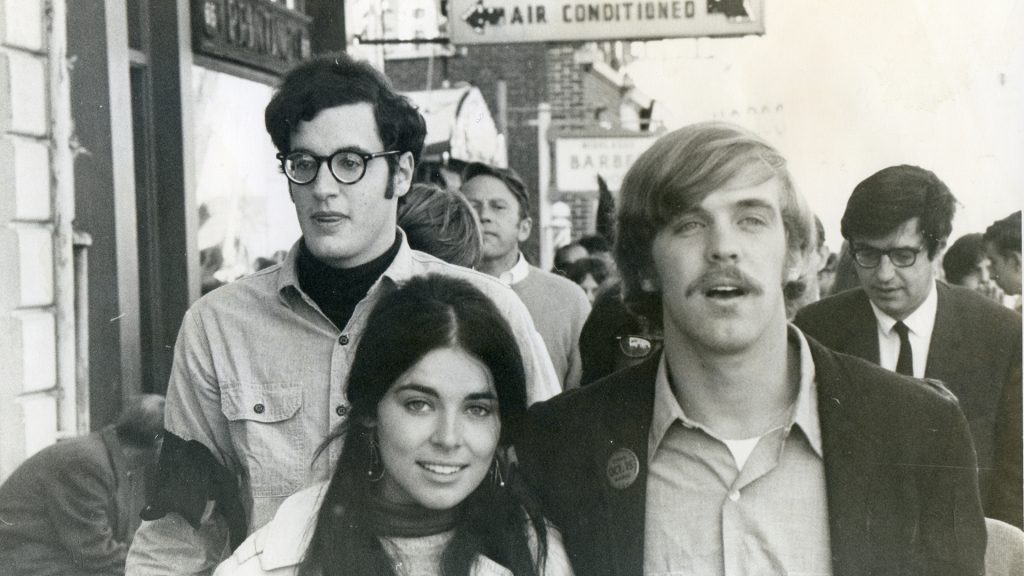

Stephen Talbot (r.) leading an antiwar march in Middletown, Conn., on October 15, 1969, with his then girlfriend Susan Heldfond, as part of the National Moratorium Day (Courtesy of Stephen Talbot)

It had all been such a long time ago, 1959-63 to be exact. So much had changed since then. He was a kid—nine when he joined the cast—and was now leading a very different life. Talbot had given up acting in his teens, veering into a career as a respected broadcast journalist and documentary filmmaker. In order to be taken seriously in those roles as he was just establishing himself, he had felt it best, during those heady days, to put his Beaver past behind him.

Leave It to Beaver, after all—which starred Hugh Beaumont and Barbara Billingsley as Ward and June Cleaver; and Tony Dow and Jerry Mathers as their sons, Wally and Theodore, better known as (The) Beaver—hadn’t been just any comedy; it had represented for millions the optimistic, upwardly mobile life of post-WWII suburban white Americans. Leave It to Beaver had practically become an adjective—to imply that someone lived a wholesome, white-bread existence, you might say, “They’re a real Leave It to Beaver family.”

Leave it to Beaver, by any measure, had been a success, but it took a while getting there. Launching initially on CBS in 1957, it had been dropped by the network after one season due to poor ratings. ABC then picked it up, though it was never a Top 30 series in any given season. Remarkably, it lasted for six seasons (234 episodes; 39 each year). Fans got to watch Beaver, Wally and their friends grow from little kids into teens and now the series lives on in reruns, airing on MeTV. [For the most part, clips from the show are not available on YouTube.] Some cast members have passed on; others are still with us.

Today, Talbot, born Feb. 28, 1949, is no longer recognized as he walks down the street—“I’m 73 now,” he told us in a 2022 interview. “I don’t look like Gilbert.”—but neither does he hide his association with the program. He’s proud of his stint as a child actor—he also appeared episodes of The Twilight Zone, Perry Mason, Lassie and other programs—and is confident that the work that he’s done in the six decades since the cancellation of Beaver holds its own. And it certainly does.

Talbot was born into a showbiz family—his father, Lyle Talbot, was a highly respected and prolific film and television actor beginning in the 1930s and continuing for decades. At one point he was a regular on The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, the show that introduced Ricky Nelson to the world, and he appeared on dozens of other programs and films of all kinds. Lyle, and Stephen’s mother Paula Talbot, were encouraging but practical regarding their son’s interest in acting, and Stephen himself knew when it was time to step away from that side of the business and graduate into the work that sustains him to this day.

We spoke at length with Talbot about his experiences as a key cast member of Leave It to Beaver, the program’s lasting impact and cultural significance, and plenty more.

This is the first of two parts.

Best Classic Bands: Let’s go all the way back. What was it like growing up in Hollywood in the ’50s and ’60s?

Stephen Talbot: North Hollywood, but technically speaking, Studio City. Basically, what happened was, I had badgered my parents as a kid to act because we were a total showbiz family. Everything revolved around my dad’s work and Hollywood and his career. All of our summer vacations were road trips; he was in summer stock around the country. But both my parents were really big on education. My mom’s parents had been teachers and school principals, and my dad had just gone to high school and my mom too. I actually went to a school that was right across the street from my parents’ house. It had the chutzpah to call itself Harvard High School. It was basically an Episcopalian church prep school, but also, weirdly, a military school. It was an all-boys school. I was still doing acting then because it was a great way to meet girls.

We’ll get to your acting career in a minute but let’s skip ahead first to why you gave it up at 14.

I liked sports, and I started to play JV football in high school. The last professional show I ever did was an episode of The Lucy Show, with Lucille Ball. But because of that show, which taped in front of a live audience, I missed a game or, more likely, a practice of some kind. I came back to practice and the coach, who I admired tremendously—he was also my English teacher—said, not in a harsh way, “Look, man, if you want to play football, you’ve got to show up. You’ve got to be here.” So I said OK, that’s it, and I went home and told my parents [I was quitting acting] and my parents said, “Cool, that’s great.” My agent was like, “What?” As I got into school, I got serious. I got interested in politics, and interested in filmmaking. I went off to college [at Wesleyan University in Connecticut], where I was an English major, but they had a formal film program. Long story short, in college, I got very involved in anti-Vietnam War protests, helping to organize them and making documentaries. I got really hooked and that ended up becoming my career. I got hired at KQED, the public TV station in San Francisco, to be an on-air reporter and producer. I was there for 10 years, making local documentaries and national PBS documentaries, and doing stories for them.

You went to Vietnam as a filmmaker.

I did, to North Vietnam. I had made a film about Vietnam veterans protesting the war. We were invited by a journalists’ association and spent a month in the country in 1974, after the peace agreement had been signed and the POWs were home.

It must have been an exciting time to be doing that kind of work, for which you’ve won numerous awards.

KQED in the ’80s was a great place to be. There were a whole bunch of us in our early thirties. We were paid very modestly, but we were given a lot of freedom to do what we wanted. I was a foreign correspondent. I did several films in Africa with Nelson Mandela’s group when they were in exile, during apartheid. They also let me do biographies of writers.

You did a biography on Ken Kesey. What was that like?

He had been one of my favorite writers: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion. I really wanted to meet him. It took a while to get next to him. He didn’t want to be in the public limelight right around the time I was making the film, 1987; his son had died tragically in a car accident. But I got to know him and he was a wonderful guy. That was one of the highlights of my working career, spending several months with him and doing that documentary. After 10 years at KQED, I was fortunate enough to get hired by [the PBS documentary series] Frontline. I worked for them for almost 20 years, and then they promoted me to run a part of the series that was called Frontline/World. I spent a lot of time recruiting younger reporters and producers, trying to get a very diverse group together and sending them out into the world.

You have a film coming up called The Movement and the Madman. What’s that about?

That is a history film of the Vietnam War era. The story is kind of amazing. In a nutshell, in 1969, Nixon’s first year as president, he and his top foreign policy aide, Henry Kissinger, wanted to figure out how they could end the Vietnam War. They came up with a secret plan, to try to threaten North Vietnam by Nixon acting like a madman. He called it his Madman Strategy privately. I interviewed a lot of people who were working for Henry Kissinger on this plan.

OK, let’s talk Gilbert Bates. You were nine when you joined the cast of Leave It to Beaver, which had already been going for a season. You had acted before that, so it didn’t come out of the blue. How did that all start?

OK, let’s talk Gilbert Bates. You were nine when you joined the cast of Leave It to Beaver, which had already been going for a season. You had acted before that, so it didn’t come out of the blue. How did that all start?

The way I got into acting was because, as I mentioned, my dad would load us all into a station wagon every summer and go do summer stock. TV knocked off production in Hollywood in the summer in those days so a lot of actors, wanting to make a little extra on the side, would do summer stock. My mom had also acted; that’s how she had met my dad, and sometimes they’d work together. He did lots of plays and what they used to call industrials, which were basically extended commercials. A company in Chicago that he had worked for was looking for a kid and I said, “Oh please, let me be in it.” My dad continued on the road touring with [my siblings] and my grandmother, my mom and I stayed in Chicago. I did this industrial, which was to sell outboard motorboats. I learned to water ski on a lake in Wisconsin. I got back to L.A. and weirdly enough, the producers said, “Hey, that turned out really well. We want to try to pitch this as a series.” My parents were going, “We don’t want you to do this,” but again, they relented because I probably was obnoxious and haranguing them. They said, “OK, we’ll get you a good agent and you can act, but you’ll always have to stay in a regular school.” So I started going out on interviews and got roles right away. My first role was in a bunch of westerns with Warner Bros., one called Law Man, one called Sugarfoot. The old joke in Hollywood was if a kid acted a couple of times and knew his lines and didn’t piss his pants, he got hired all the time.

You were on a lot of great shows: The Twilight Zone, Perry Mason, Lassie. Was that all contemporary with Beaver?

Basically, I started acting when I was nine [1958] and I worked on many shows. Beaver was the only show where I played the same character, Gilbert. I did almost 60 episodes of that. And of course that’s endlessly repeated. Who knew at the time that was going to last forever? But, at this same time, I was a really busy kid actor. Twilight Zone was my personal favorite show as a kid at the time. It was a total thrill. I met [host] Rod Serling. He was as impressive as he was on TV. He had that gravity in his voice, and he looked like a character out of Mad Men, with a thin tie. Very serious, very smart, very nice man. Being on Perry Mason was a trip. Wanted: Dead or Alive with Steve McQueen, who played a bounty hunter—he was a very cool, intimidating, distant kind of guy, a rebel without a cause. I had a great time. I really looked forward to acting. I was in a bunch of Lassie shows. The most fun shows, frankly, were the ones where I played different or strange characters, or we were on location someplace.

Watch Talbot in Perry Mason (1960)

Then you got the Beaver gig. What was it like for you to be a regular cast member on such a hot show?

Beaver got to be, not routine, but it was a job. And it wasn’t every week. I had this really weird arrangement where they would call me up from the studio and say, “We’d like Steve to be in next week’s show,” or two weeks away. My parents would go, “How’s school going?” and I would say, “I got a test next week. Can’t miss it,” or something like that. And they’d go, “Sorry. He can’t be in the show,” and they would go OK. I did pretty well in school in those days, so most of the time it was fine and I would work two or three days on an episode, miss school those days and then come back to school.

Listen to the opening of Beaver, embedded in every baby boomer’s head…

I want to run the names of some of the major cast members by you and get your impressions of them. Let’s start with the Cleaver family: Ward and June were played by Hugh Beaumont and Barbara Billingsley. What was Hugh like?

Well, Hugh was an interesting guy. I later learned—I didn’t know at the time, although maybe my dad or mom had mentioned it to me—that he had been in a lot of movies. He was a very good actor and was in a bunch of film noirs. Jerry Mathers always talks about when he [Beaumont] played a hard-ass detective who used to rough people up in questioning. The other thing about him, which I did know at the time, is that he was a minister, I believe a Methodist, and part of his doing Leave It to Beaver was that his church encouraged him to pass on good all-American family values and so forth. So he took his role seriously. He was a tall man and he was serious most of the time. I was always polite around Hugh Beaumont. The other thing that happened is, he wanted more of a challenge. The show was based around kids and he and Barbara were key to it, but he ended up asking to and then directed many episodes. He was, again, a very serious, no-nonsense kind of guy, not that different from his character.

The Cleavers, circa 1957 (clockwise, from left) Tony Dow, Hugh Beaumont, Jerry Mathers and Barbara Billingsley (publicity photo)

And Barbara Billingsley?

My main scenes with Barbara were ringing the doorbell to the Cleaver house. She opens the door in pearls and says, “Oh, hi Gilbert. Beaver’s upstairs.” It’s not like we had a lot of meaningful engagement. But she was always very nice, never a mean word to anyone in the cast or to us kids. She was very attractive and sweet, so also not unlike her character.

When you came into the show, it was already going. Was that difficult because the others already had relationships with each other?

It was, yeah. But I had walked into a lot of shows, because mainly I was a guest actor in shows. So I was very used to dropping into a show and figuring out who’s who in the cast, whether it was Donna Reed or working with an actress like Barbara Stanwyck on her show. You figured out, oh, this is a movie star I’m working with, or this is just another kid like me. So the show had been around for a couple of years and they were much younger. Jerry always says when he started doing the show, he didn’t know how to read yet, so he learned his lines by his mom reading him his lines and he would memorize the line. He really carried that show and he started really young. He had had some acting experience before. So by the time I got on the show, age nine, they really brought me in because they were always introducing new friends, but also, essentially, to replace the Larry Mondello character.

What happened to Larry Mondello, played by Rusty Stevens? The usual story that’s told is that his real-life mother was very overbearing and the network wanted to get rid of her.

That’s the story. I was a kid so I didn’t really know. That’s what Barbara Billingsley has said. I would tend to believe that. He was a good kid actor and it was a funny role. The audiences liked him. I liked him. He used to just crack me up. He was very deadpan. In real life, he was totally deadpan too. I haven’t seen him since I was nine or 10. I used to think there was a little W.C. Fields in him, but it was not conscious. He just had this funny persona. He was a nice guy. Early on, it was basically Larry, Whitey [the late Stanley Fafara] and Gilbert, when I got into the show. But something happened, because he had been a regular and then he disappeared and then suddenly the character of Gilbert became Beaver’s main friend.

Beaver was portrayed as a little bit dumb, very naive, very easy to manipulate. How did that image contrast with the real-life Jerry Mathers?

He was smarter and sharper than the character. Jerry carried that show. The more distance I have on it, I see that. You see him age over the years, from this very cute, freckle-faced boy. He was an Everykid who always gets himself in trouble, and his older brother’s the smart one. If you look at the last two years, he and I are both teenagers. Jerry was a year older than me, roughly, but we were teenagers and we were, physically, completely different. We were both taller than Tony though; he was a very athletic, handsome guy, but he was short. Also, our voices began to change. Jerry’s changed first, before mine, and he was really proud of the fact that his voice had changed. He used to lower it further, artificially, and the directors would cut the scene and go, “Come on, Jerry, what are you doing? You’re still a kid. Don’t do that voice.” They were trying to hold us back, and Jerry and I—who had become quite good friends the last two years, the guy I knew the best on the series—both wanted to grow up. He began to chafe against some of the situations where he was supposed to play dumb. So, they finally had some episodes where we were interested in girls. One time, I was doing a scene in closeup and the director shouted to cut and said, “What’s that on his lip?” I had mustache hair. Someone said, “Lose the mustache!” My dad happened to be my guardian that day, and they went to him and said, “Is it OK if we shave it off?” And my dad agreed and they shaved me. We were also getting into rock and roll, Jerry and I. I remember once sitting down with him and trying to decipher the lyrics to “Louie Louie.” We went to dance parties and early teen dates. He was a friend, and I admired him for having carried the weight. He never complained. He was totally professional. If he had broken down, if he’d been a diva, the whole show would’ve fallen apart. But toward the end, we were enjoying the experience of hanging out together and having a little more room in the show to grow up, but also chafing against it.

Did you guys keep in touch afterwards?

We did for a while, but to be completely honest, no, and I have some regret about that. We both lived in the San Fernando Valley, and we both went to private schools. He went to Notre Dame, the big Catholic high school, and we both played football in high school. We stayed in touch for a while and then we completely drifted apart.

What about Tony Dow?

Tony was older. On the set, there were basically two groups of kids. There were the teenagers, Tony and Eddie [Haskell, played by Ken Osmond] and Lumpy [Frank Bank] and that group, and then there was Beaver and his friends. Beaver and Wally, obviously, overlapped tremendously, but we [Tony and I] were sort of in our separate worlds. We had scenes together, but it wasn’t like working with Jerry, or Richard [Correll] or Whitey. Tony couldn’t have been nicer. He was sort of the icon of the ideal elder brother. He was low-key, very straightforward. Sometimes, so we could blow off steam and just have fun during lunch breaks, they had a little basketball court. I remember playing pickup basketball games with him. He could always out-shoot us. We’re not close, but I’ve been in contact with Tony Dow over the years. He remains a really interesting guy. He became a sculptor.

Related: Our obituary of Tony Dow

Neither of them did much acting after the series. It must have been difficult for them to get adult roles after being Beaver and Wally Cleaver.

Kids acting get typecast. Or, you may look one way as a kid and then you’re different as a teenager and adult. I had conversations with Tony Dow about this, never really with Jerry. Tony has struggled with depression—he just recently did the CBS Morning Show and the whole episode was about his depression. I never knew about it at the time when we were making the series, but part of his depression was that, until much later in life when he ended up becoming a sculptor, he had never really found an acting career. Tony actually worked a little more than Jerry. He was in soap operas and a bunch of TV shows. And then, at a certain point, the two of them, for better or worse, realized, “This is our meal ticket,” and they did dinner theater shows together and they did the [LITB] reunion show in the ’80s. [Ed. note: Talbot was asked, but refused to participate in the reunion series because he was busy with his film and TV work.] It lasted five or six years or something. He had gotten into some directing, doing commercials, and he called me up and he said, “You’re lucky, because you were able to enjoy the series, make a little money from it, and then, because you weren’t the main character, you could move on.” Jerry and Tony were stuck, and that was part of Tony’s depression, for sure. I know Jerry tried a lot of things. He was a smart guy; he went to UC Berkeley after Notre Dame. I sort of feel bad for those two guys in the sense that they’re kind of stuck in this time warp. On the other hand, they’ve achieved TV immortality, no small feat.

“Good morning, Mrs. Cleaver. That’s a very pretty dress.” Ken Osmond (center) as Eddie Haskell, with Tony Dow (Wally, at left) and Barbara Billingsley (June Clesver)

Wally’s best friends, as you mentioned, were Eddie Haskell and Lumpy Rutherford. In my opinion, Eddie would have done the best in today’s cutthroat world because he wouldn’t let anything stand in his way.

Exactly. And between Ken Osmond and the writers working together, he created, I think, the one truly indelible character. Not many people can say that they created a character where just the name becomes something that, in American culture, for years and years and years, people knew. That’s just amazing. He was something like six or seven years older than me, and his character, of course, was always teasing or bullying or harassing Gilbert. And the truth is I was a little intimidated by him. I always kind of kept my distance and didn’t particularly like him. That’s unfair because, as Jerry and Tony have told me many times, off-screen he wasn’t like that. He was very friendly and the three of them got along famously. They always said he was a really nice guy, but I always had my doubts. I thought, hmm, Eddie? Ken? The same guy? I’m not going to let him get to me.

Related: Ken Osmond died in 2021

Do you have a favorite Eddie moment in the show?

There’s one episode that I watched a while back, where Wally is supposed to take Beaver and his friends, including Gilbert, on an overnight camping trip. They’re trying to terrorize the kids by playing a record of mountain lion sounds, and then a real mountain lion comes along and Eddie runs and falls off a cliff onto a ledge. He turns into a whimpering coward and needs to be rescued. Everyone goes off to find the park ranger and he says, “Don’t leave me alone.” And there’s a great line where they say, “OK, Whitey will stay with you,” And he goes, “No, not Whitey, he’ll throw rocks.” So Gilbert is left alone with him, and Eddie is begging Gilbert, “I’m lonely. Talk to me.” Gilbert says, “What should I say?” And so finally, finally, I get my one chance in 57 episodes to tell him what I really think, which is to say he’s a jerk and a horrible guy. The writers gave me that one chance.

Watch a brief clip featuring Talbot’s character

The complete Leave It To Beaver series is available here.

Enjoy Part 2 of our interview with Stephen Talbot, including his reminiscences of hanging out with the Beav—and Muddy Waters—those weird Beaver-died-in-Vietnam rumors, and the dark side of Leave It to Beaver (yes, there was one).

17 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationWhat a fabulous interview. Most of these kid actors are never heard from again. Gilbert was not my favorite as Mondello stole every scene he was in but I liked hearing from Talbot after all these years. Maybe you can get Larry next or one of Wallys High school girlfriends.

Great interview. Nice to see that not all child actors end up like Alfalfa. The smart ones (for example Dwayne Hickman, who died in January) learn from their exposure to the business.

It was fun to see Tony Dow (and the ersatz Beaver) deconstruct the character in “Kentucky Fried Movie”.

Same with Mathers on “Married With Children”.

Yes, excellent reading on your interview with Steven T on his experience as a

on and off cast member on “Leave it to Beaver”. I continue to watch the reruns of the show on MeTv network.

The show is truly “a feel good” moment every time I watch it. (I was born in ’52)

Still love to watch the show. I recently read that Tony Dow has cancer. I remember him in the soap opera (many years ago) Never Too Young. “Gilbert” grew up to be quite handsome, and Jerry Mathers seems like he would be very down to earth. Yes I am in the senior citizen era.

Yes it took me back to my childhood for sure when all my brothers and mom were still alive. I’m the only one left in my family but I do still watch LITB. And I tell my son and husband I remember getting off the school bus and us friends would all sit in front of the TV to watch 30 minutes of LITB. Then we’d all go out side ride our bikes to the store and we’d buy a bag of candy (banana taffy and super bubble.) By the time I got back to my aunts house mom was there from work. We’d go home mom would start cooking and I’d do my homework while watching GI then everyone sat down to dinner about 6pm or 6:30pm as soon as dad got home from work. If only I’d know then what I know now those were the best of times.

“Gilbert” was/is my favorite of all of the Beaver’s friends. In fact, except for “Wally,” he was my favorite character. I have wondered what a series which essentially featured Tony Dow and Stephen Talbot might have been. This is an outstanding interview. If I had ever known of Tony’s depression, I had forgotten it. Now, he is battling cancer. My heart goes out to him, and hope that this situation does not cause his depression to worsen. There were some characters whom I simply did not like. That probably speaks well of their acting skills, since they were supposed to be basically annoying, if not unlikable. But, I won’t mention names. Suffice it to say that, of all the LITB actors, Stephen and Tony are the two whom I would most like to get to know — even now. I’d still be the baby in that meeting; I was born in late ’54.

Well who knew any of this about Gilbert? Way to go bro, sounds like you led an exciting life and it’s awfully nice to see your parents let you do things that you wanted to do, kudos to them. I still watch LITB on MeTV, those shows have held up well, some episodes are so funny! For whatever reason I am obsessed with Hugh Beaumont lol… always heard good things about him too. Really good interview and I look forward to part 2

I noticed that Tony Dow / Wally would always used his arm/hand as if something was on his nose I don’t know if that was part of his character for the show or was he just nervous.

Very in-depth and interesting interview, and looking forward to o Part II.

I have always said to friends and colleagues:

“Everything you need to know about how to conduct your life could be learned from the lessons embedded in the “Leave It To Beaver” episodes, regardless of where, who, how , or when you started out in life.”

I often say the same! I think LITB should be a school requirement…

Brings back the same warmth as the reruns and even the original show. What a great real life Gilbert lived. I envy him. I would’ve loved summer acting and going away on family road trips. I was born in the early fifties and grew up in the sixties. I was involved in protesting Vietnam War too. I almost got drafted by lottery number. What great stories these two parts were. Thank you, thank you.

I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading this revealing interviews with Steve. It was so informative, interesting and enjoyable. A lifelong fan of the show I loved every character.

I got to meet Steve Talbot in 1975, when he was a “guest speaker” at SUNY College at Old Westbury, NY, for my “Investigative Reporting” class! He made no attempt to identify himself as a former actor, but concentrated on the subject, at hand! He & the teacher, Deidre English, did a great job & I was lucky to receive an “A+”!

Steve’s father, Lyle Talbot, was a terrific character actor, who should have been given more leading roles! Best of luck! Glad to have met you!

What a fascinating insight into Stephen Talbot’s life after “Leave It to Beaver”! It’s amazing to hear how he transitioned from child star to a successful documentary filmmaker. I loved the show growing up, and it’s interesting to see how those early experiences shaped his career. Thanks for sharing this interview!

I loved reading this post! Stephen Talbot was such a memorable character on “Leave It to Beaver.” It’s fascinating to hear about his journey after the show. Thank you for sharing his insights and updates on his life!

What a fascinating read! I’ve always wondered what happened to the child actors from “Leave It to Beaver,” and hearing from Stephen Talbot was a real treat. His insights into life after the show and his career choices are truly inspiring. Thanks for sharing this interview!

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it.