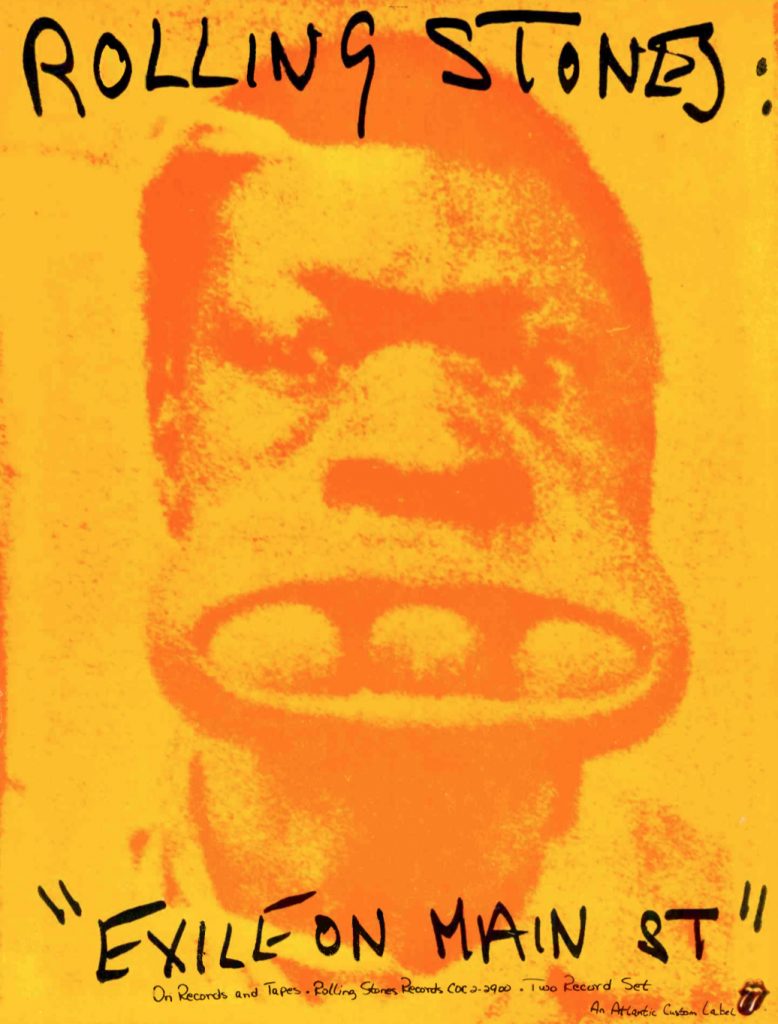

Rolling Stones ‘Exile on Main St.’: An Interview with Engineer Andy Johns

by Harvey Kubernik In early 1972, The Rolling Stones, record producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Andy Johns relocated to Hollywood after cutting the basic tracks for Exile on Main Street in the 16-room Villa Nelcotte in the South of France. Overdubbing and mixing sessions were then done in Hollywood at the landmark Sunset Sound Studios and mastered at Artisan Sound Recorders on the same street.

In early 1972, The Rolling Stones, record producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Andy Johns relocated to Hollywood after cutting the basic tracks for Exile on Main Street in the 16-room Villa Nelcotte in the South of France. Overdubbing and mixing sessions were then done in Hollywood at the landmark Sunset Sound Studios and mastered at Artisan Sound Recorders on the same street.

Johns, born May 20, 1950, was a world-class sound engineer and record producer. The younger sibling of Olympic Studios engineer Glyn Johns, Andy graduated the King’s School, Gloucester, England, in the late 1960s. Before he even turned 19, he was running the dials as Eddie Kramer’s second engineer on classic recording sessions by Jimi Hendrix.

Johns’ name can also be found on the Stones’ Sticky Fingers, Goats Head Soup and It’s Only Rock ’n Roll, as well as recordings by Led Zeppelin, Free, Blind Faith, Jack Bruce, Steve Miller and many others.

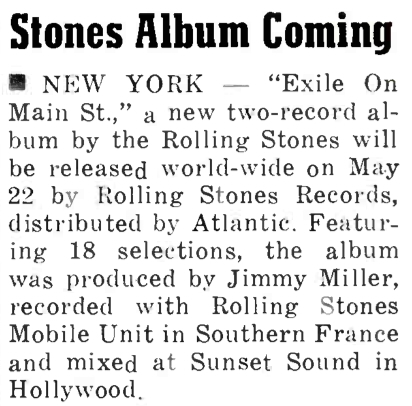

This news item from the May 20, 1972, issue of Record World confirms the release date of the album.

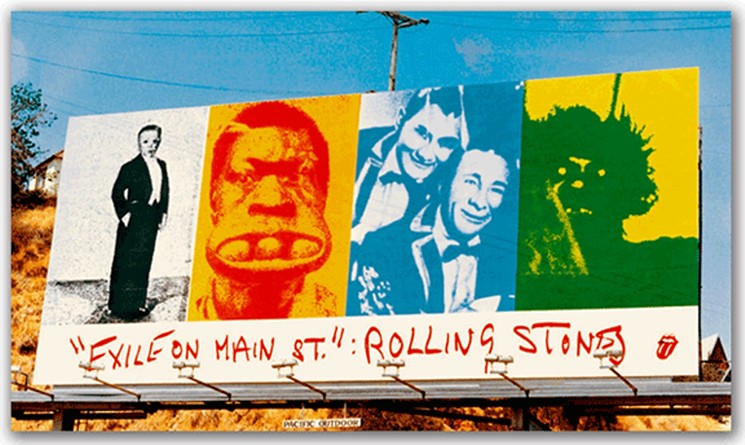

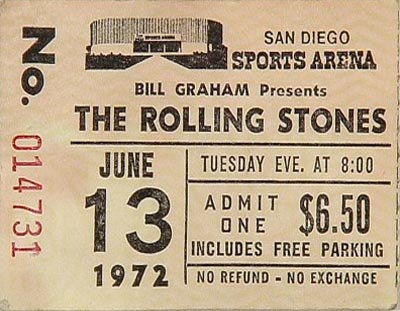

2022 marked the 50th anniversary of Exile, which spent four weeks at #1 in the U.S. following its May 22, 1972, release. In 2010 we talked at length about the album. Johns died three years later, at age 62.

Best Classic Bands: You had a history with the Rolling Stones before engineering Exile on Main Street. You were a tape operator at Olympic Studios for Their Satanic Majesties Request, and knew the band even earlier, owing to your brother Glyn engineering their sessions from the beginning of their career.

Andy Johns: I was aware of them when Glyn did their first demos at IBC. They didn’t even have a record deal. I remember him bringing that stuff back to the house. They soon started making records. Glyn used to live with [Stones pianist] Ian Stewart.

You were involved with [1971’s] Sticky Fingers and with producer Jimmy Miller.

I got to work with the Rolling Stones because of Jimmy Miller. I’d worked with him as an assistant engineer at Olympic, and then moved over to Morgan Studios. And they made me a full-time engineer almost instantly. I was the only guy there. I did all the sessions that came in and got a lot of experience quickly. I did Traffic’s “Shanghai Noodle Factory” with Jimmy. And then we worked on the Blind Faith thing. He came in about halfway through on that. Mott the Hoople. Sky, Free’s live album. Then there was a Stones session that he brought into Morgan, the first session on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” And it went very badly. Just horrible. They did not want to be there and there were too many of them for that little place. [Keyboardist] Al Kooper was there, I think. That was my first opportunity of working with them. And Mick was in a foul mood, telling me to turn Brian [Jones] off. I didn’t do that many sessions on Satanic Majesties. It was bizarre. And I thought it was pretty silly stuff. You got Bill Wyman out there playing vibraphone? And some other bizarre instrument that Charlie [Watts] was playing. It was just a very poor attempt to compete with Sgt. Pepper’s. [Manager/producer] Andrew Loog Oldham was still around but not very much and not much of an influence on anything. The last time he was around was during the “We Love You” and “Dandelion” recording sessions at Olympic when the cops showed up at the door and Mick was smokin’ a big joint. These are a couple of bobbies in uniform. And Mick was so brilliant. He puts this joint behind his back and says, “Andrew, what we need on this are two pieces of wood bein’ hit together in unison. Like claves.”

“What about these?” offered the bobbies as they voluntarily pulled out their truncheons. So he escaped by puttin’ them on the record. And Andrew was spraying the control room to cover up the smell. At the time the Stones were having vast hassles with the cops and another bust would have been the end for them. So, it was a very narrow squeeze. Jimmy then gets me in on Sticky Fingers, which was about half done. The Stones has just finished putting together their recording truck. I don’t know where the money came from. The truck was done for Stew, if anything, because he had been so hard done by them. So, they said, “OK, Stew. You run this.” And we went to Stargroves [Jagger’s Berkshire mansion] and they played for a couple of days. Not very well. And then the first playback comes. And they have all these f**king hangers-on. It was just ghastly. I did the first playback and Mick is leaning over the mixer at me and he says, “What the f**kin’ hell is that? I could do better than that on my Sony cassette machine. What are you doin’ here?” I thought, “Christ, what a nightmare.” I said, “Well, if you got rid of these bloody people, it’s a small space, and they’re soaking up all the sound and God knows what else. And then we’ll listen again.” And Mick says, “You’re worse than your brother.” I said, “No I’m not.” I waited up to speak to him the next morning and I said, “Look, obviously the Rolling Stones are far more important than my feelings. If I should go, I will go right now.” He went, “No. You’re in. You’ve passed the test.”

I heard many years ago that you were actually being considered to replace Bill Wyman as bassist for the Rolling Stones.

During Exile in France one night, Mick went, “You know, maybe we should get someone else.” And I’m sitting in the recording truck, and said, “Look, this probably wouldn’t mean that much to you, wouldn’t change anything, but if you get rid of Bill Wyman I’m going home.” Bill is one of my heroes.

Did you have to make adjustments to record in a villa, a home?

I don’t know about adjustments. You just go with what is there. You try and make it sound as good as you can. The first room I put them in was this basement, which was a disaster. It just was too dead. So I moved them to another room that had stone walls, and I had Charlie and Keith in there and Mick Taylor. Bill had his bass underneath the stairs. [Pianist] Nicky Hopkins was in a separate room. It was tough, but some of the things came out rather well. Bianca [Jagger] was very pregnant at the time and I think she showed up once or twice. She had the baby during the record. Mick was back and forth to Paris a few times.

As far as microphones on hand, I had the normal standard stuff. The mikes were OK. It was just these rooms were a bit weird. Plus, it had been a torture chamber during World War II. The villa was a local Gestapo headquarters when the Nazis occupied France. I didn’t notice that until we’d been there for a while and the floor heating vents in the hallway were shaped like swastikas. I said to Keith, “What the f**k is that?” “Oh…I never told you?”

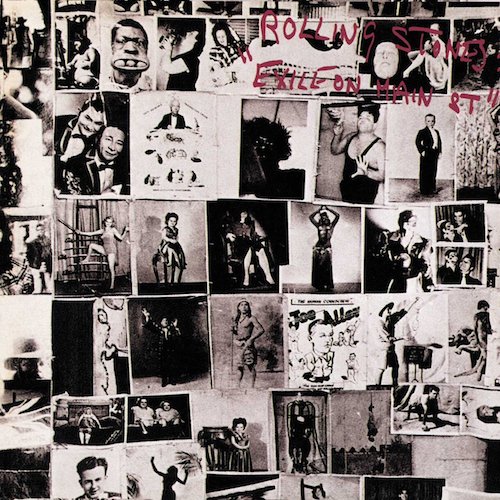

Related: Behind the Exile cover art

Let’s talk about a couple of the songs, starting with “Tumbling Dice.”

Obviously, it was going to be great but it was a big struggle. Eventually, we got a take. I thought, “Let’s kick this up a notch and double-track Charlie.” “Oh, we’ve never done that before.” “Well, it doesn’t mean we can’t do it now.” So we double-tracked Charlie but he couldn’t play the ending. For some reason he got a mental block about the ending. So Jimmy Miller played from the breakdown on out. That song we did more takes than anything else.

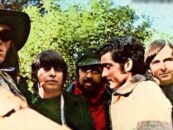

The Stones in 1971, hyping Exile‘s predecessor, Sticky Fingers. l. to r.: Charlie Watts, Mick Taylor, Bill Wyman, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger.

“Rocks Off”?

It went on for ages. When Mick came back from Paris for the first time, he seemed happy with the sound. Keith would sit downstairs and at one point he sat there for 12 hours without getting out of his chair, just playing the riff over and over and over. Then one night, it was very late, four or five in the morning, Keith says, “Let me listen to that take again.” He nods off while the tape is playing. I thought, “Great. That’s it. End of the night and I’m out of here.” So I go back to my place where I was staying. I walk in the front door and the phone is ringing. It’s Keith. “Where are you? You better get back here, man, ’cause I have this guitar part. Come back!”

What was Jimmy Miller like as a producer?

Jimmy was an extremely talented man. His main gift was his ability to get grooves, which for a band like the Stones is very important. Look at the difference between Beggars Banquet and Satanic Majesties. He was quite influential and came up with all sorts of lovely ideas for them. In fact, that’s him playing the cowbell at the beginning of “Honky Tonk Women.” By the time we got to Exile on Main Street, they weren’t really listening to him anymore so he felt a bit like a fifth wheel. He was being squeezed out a bit and I was watchin’ that go down.

How would you describe Mick Taylor’s contributions on guitar?

Mick Taylor in the studio in France, or Sunset Sound, was just a shining light. We’d do 100 takes on something and he would come up with something slightly different every time. Faultless.

Nicky Hopkins is all over the Exile album.

Nicky is on everything. He was the best and the greatest. God bless Nicky Hopkins. He added so much to that band. Sometimes you wouldn’t really notice it. But if you take the piano out then the house of cards collapses a bit. He was always coming up with gorgeous little melodies. “She’s a Rainbow” [on Satanic] That’s Nicky. Plus, he was extremely rhythmic. People don’t remember him for being rhythmic. But he was.

What was the first song actually completed for the album?

“All Down The Line.” Mick got very enamored. “It’s finished! It’s going to be the single!” I thought, “This isn’t really a single.” I remember going out and talking to him and he was playing the piano. “Mick, this isn’t a single. It doesn’t compare to ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ or ‘Street Fighting Man.’ He went, “Really? Do you think so?” I thought, “My God. He’s actually listening to me.”

Listen to “All Down the Line” from Exile on Main Street

What is the magic of the album to you?

I think they were at the height of their powers as far as rock ’n’ roll goes. Those pop singles and albums they made in the ’60s were stunning. But Exile is mostly blues-based stuff. “Stop Breaking Down” is probably my favorite track. I remember getting Mick to play harmonica on that. It did not seem like it was finished. My brother [Glyn] had recorded earlier. I said, “We’ve got to use this,” because Mick Taylor plays some gorgeous lines and I’m very sure that it’s Mick Jagger playing the rhythm guitar as well. That’s why it’s a little choppier. It’s an intangible. Exile just turned out to be a great collection of music. And I think it was good that it was a double album. Some people say it should have been a single album but you get the feeling of what they were going through of the time and the confusion and the angst and the joy and the drugs and they moved out of England. There were a lot of emotions.

Watch the Stones perform “Tumbling Dice” in 1972

When the Stones tour, tickets are available here and here.

[Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThis is a fabulous interview. The right questions about the right people. Thanks so much!

That the Stones eventually stopped listening to Jimmy Miller explains a lot about what happened to their records after the “Core Four.” And then of course when they dispensed with bringing anyone else on board and produced their records themselves in the mid-seventies marks the beginning of when their subsequent records began to sound all the same, and the end of the Stones classic records period.

I did sound for the Exile tour when I worked with Tycobrahe Sound. Jim Chase mixed it and I worked on stage. It was a really amazing experience. But that was 51-years ago and a great memory now. I was 22 then.