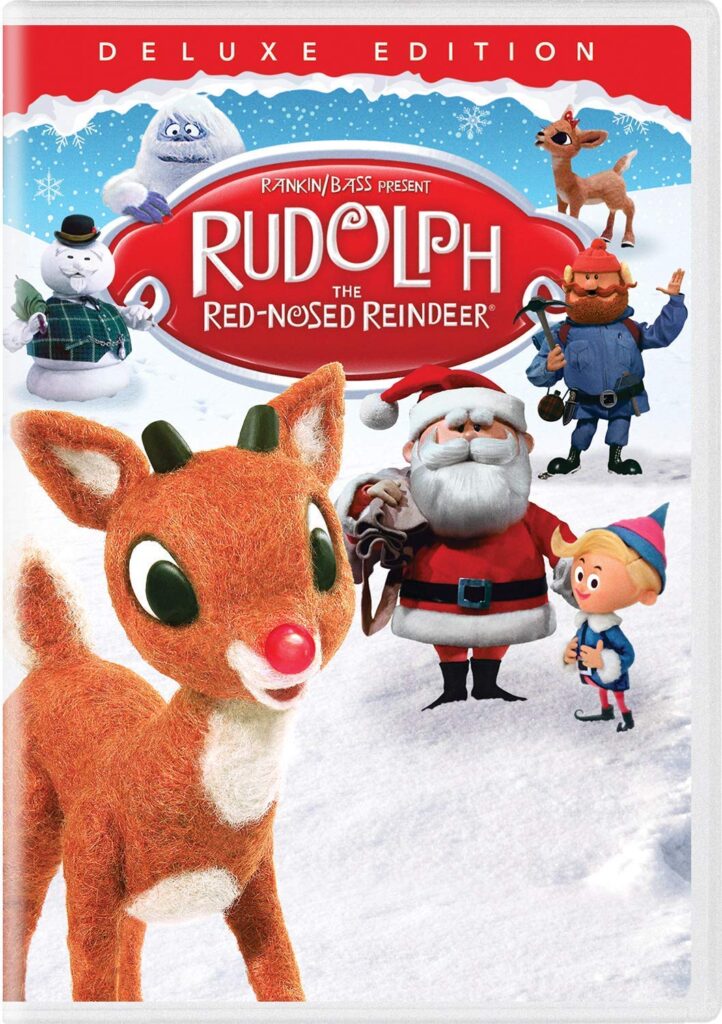

The Radical, Socially Progressive Art of Rankin/Bass’ ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’

by Colin Fleming In December 1964, Americans had their first meeting with a creature who, in his own words—though he was anything but self-aggrandizing—was a dear of a reindeer.

In December 1964, Americans had their first meeting with a creature who, in his own words—though he was anything but self-aggrandizing—was a dear of a reindeer.

Some of them may have already known of him, thanks to a 1939 poem by Robert May and a song from that same year by Johnny Marks—more on this apace—as well as a 1948 Max Fleischer cartoon, but they didn’t know him as they were about to know this fine buck named, of course, Rudolph, he of the refulgent red nose that could cut—and still can—through any storm, including the likes that can cancel Christmas.

There is perhaps no Christmas special more beloved than Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass’ Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Little looked like it at the time, with Rankin/Bass pioneering what they called Animagic—a form of stop-motion animation that seemed to exist nowhere else save within the duo’s wondrous world where Santa Claus was nonetheless almost always stressed and hectoring, snow men talked and misfits banded together to save the day.

The Rankin/Bass team would go on to make a litany of specials, a goodly amount of which also featured the Christmas holiday, and they could get downright loopy, even crazed. Many a nightmare owes its origin to the Heat Miser from 1974’s The Year Without a Santa Claus doing his theme song with those mini dancing versions of himself. But Rudolph was pure class, the lone Rankin/Bass production that counts as artful and inspired. But that’s just one thing it is, and not the most surprising.

In Messiah, Handel wrote about Jesus Christ as someone despised. Rudolph had it pretty bad, too. He was mocked, bullied and barred from those reindeer games we’ve all heard so much about. Simultaneously, the special is more tuneful, thanks to Johnny Marks’ title song and an equally euphonious set of songs, the most addictive of which has to be “Holly Jolly Christmas,” delivered by Burl Ives as history’s most ingratiating snowman. But then there’s this present to unwrap: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer is also among the most socially progressive works in the history of American television.

When I watched this as a kid—which was well after 1964, but as soon as I was old enough to do what all kids seemingly do—I remember thinking there was some extra stuff going on here that wasn’t just about Christmas and wasn’t only about bullying, either. Rudolph gets pasted right from birth. He’s about a minute old and his father is telling him he’s a f**k-up as result of being born with a glowing nose. No sooner has this squall died down before Santa arrives at the family cave and dishes out some abuse of his own.

Then we have Hermey the elf, who is screamed at by his boss and told he’s worthless. And we all know how the reindeer games go after Rudolph’s fake nose—which Ives’ Sam Snowman tells us was intended to cover up his “nonconformity”—falls off and everyone—the kids, the adult in charge—flay him alive with their words and laughter.

Rudolph and Hermey

Related: Looking for some classic rock Christmas albums?

But it’s after Clarice—the reindeer who is still kind to him—gets caught walking with Rudolph by her dad that Rankin/Bass made it clear the message they were really sending with this special. I’ll never forget first hearing how her father practically spits the words right out of his mouth—like they were laced with venom—in saying that no girl of his will ever be going out with a…red-nosed reindeer. He lands hard on that red. It’s all about color for this bigot. This is someone who could have said “Black guy” or that other word, and we all know what that word is.

The year 1964 was a flashpoint for the Civil Rights Movement. Rudolph was doing its part in no less meaningful a way on the arts and entertainment front than the likes of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” without receiving the same amount of credit, because of its holiday veneer.

Watch an NBC-TV promotional spot for Rudolph… from 1964

But make no mistake about it: Rudolph is a Messianic figure in his own special, someone who has it rougher than George Bailey did in It’s a Wonderful Life, but doesn’t rate suicide as the option that the latter does. Bailey was willing to abandon his wife and kids; Rudolph, who has no one, seeks to find others whom he can help. Think how much time passes in Rudolph with our hero on his own (he grows up, Sam tells us), wandering the unwanderable North Pole (being landless and all). Until he meets his buddy, Hermey the former toy-making elf.

Rudolph was the Black guy and Hermey was the gay guy. And they became fast friends, self-proclaimed misfits who were in actuality the coolest individuals up there in Christmas Town. Elf, deer, didn’t matter—you identified with these characters as humans, but they are also symbols of larger forces, ideas, aims; totems of inclusivity. Exemplars. Reminders. Sources of inspiration.

The homosexual imagery and language is plain and to see it throughout Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer doesn’t make one some dry academic on the hunt for that which is not there. Look where Hermey stands—right beneath the undercarriage—of the Abominable Snowman after relieving him of his teeth, which has its own implication. Note Rudolph’s posture—his derriere is the crux of the composition, smack in the middle of of your TV set—as he gets a drink from a pond. There’s a character named Fireball. Three guys—once Yukon Cornelius makes the duo a trio—share a bed in a cozy cottage with snow flowers. In proto-Deliverance fashion, the gay elf squeals— strategically—like a pig.

Rankin and Bass—abetted by scriptwriter Romeo Muller, whose name sounds like that of someone who’d compose this particular story—didn’t know that they’d go on to be constant purveyors of holiday fare and, let’s be honest, a particular brand of holiday treacle. There is no Rankin/Bass production I won’t watch a limitless amount of times, but they aimed higher with Rudolph, as if it might have been their only chance to say what they wanted to say in a time when much needed saying. Then again, what was true then is true now.

I think we love this special because we’re all misfits—or that is a going concern everyone has, anyway. What is wrong with me? Where do I fit in? How are my people? Who is my person? The special hits on that personal level. But Rudolph also took up the cause of race and sexual orientation because it’s ultimately a work about identity and the dignity that all humans, as humans, are owed. Each of us should be allowed our chance at those reindeer games. If you can’t fly as well as someone else and land that spot pulling Santa’s sleigh, then so be it. But the playing field is level for all races, creeds, orientations.

Rudolph hit me hard the first time I saw it, and it’s hit me hard harder each of the times since. The story is dark, but it is light—both literal and metaphorical light—that triumphs. The light from within is what actuates Rudolph’s light from without. He is a deer for others. Despite his own pain, he thinks of others first. Rather than put his friends at risk, he goes it alone.

Now, we might say that we needn’t try to go it alone when we have friends, but Rudolph thinks he’s helping them. Which is the point. Of what? Everything. If there’s a single thing that people are here for, it’s to help each other. Christmas is the holiday that encapsulates the ideal; which isn’t to say that the ideal doesn’t have daily practical application. Look at Hermey and Rudolph. They get it.

Hermey and Rudolph are down—shunned, insulted—but they never give in. They help each other rise from their first moment together when Hermey pops up out of a snowbank. If you’re going to create a Christmas-centric work that lasts, it has to be about more than Christmas. We can say that what really Christmases Christmas, if you will, is something more than Christmas. Linus Van Pelt understood as much. So too did Ebenezer Scrooge, after he’d been visited by enough ghosts. And the same may be said about Rudolph and Hermey, the would-be outsiders who instead fostered community while still being true to their highly individualistic selves.

Is this radical, agitprop art? You bet your last candy cane it is. It’s unflinching and raw and real and cutting-edge and vital. The kids will love it because kids always have. Increasingly, I think kids are our best and brightest because they are open to possibilities in ways that adults often are not. Watch Rudolph with them this year. And watch Rudolph with the kid inside yourself. Find that kid if you’ve not spent time with him or her in a while.

It’s the light on the inside that cuts through the storms of storms, the storms that range beyond matters of the meteorological. And that’s a truth—for everyone of every age—as plain as the nose on a certain reindeer’s face. A very special nose at that.

Watch the original commercials for Rankin/Bass’ Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

The production, along with books, figures, and other items, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationMADtv did a bunch of hilarious parodies in the 1990s. Two of the best were ‘Raging Rudolph’ and ‘The Reinfather’. Check them out on youtube.

The writer’s one mistake is looking at a children’s show and trying to understand it as an adult. He’s way too old in his head to enjoy this holiday classic. I saw it first time around at age 9. It was cool how the puppets moved . Not unlike Davey & Goliath but on a larger scale with music.

It’s interesting as an adult to notice the instrumental medley during the opening credits are that of the musical songs that will come later in the show. The only way to enjoy this classic is to watch with childhood wonder and leave all your adult life problems in the next room.