On March 16, 1971, the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences broadcast the presentation of the Grammy Awards live on television for the first time. Paul Simon made a number of trips to the Hollywood Palladium stage that night, only twice accompanied by his longtime performing partner Art Garfunkel. Collecting awards for their best-selling album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, and its title track (Song, Album and Record of the Year and Best Contemporary Song), Simon had five awards and Garfunkel two at the end of the night. Simon shared the nod for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalists with keyboard ace Larry Knechtel; Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical went to industry veteran Roy Halee, who made every corner of Simon and Garfunkel’s work in the studio sparkle.

On March 16, 1971, the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences broadcast the presentation of the Grammy Awards live on television for the first time. Paul Simon made a number of trips to the Hollywood Palladium stage that night, only twice accompanied by his longtime performing partner Art Garfunkel. Collecting awards for their best-selling album, Bridge Over Troubled Water, and its title track (Song, Album and Record of the Year and Best Contemporary Song), Simon had five awards and Garfunkel two at the end of the night. Simon shared the nod for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalists with keyboard ace Larry Knechtel; Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical went to industry veteran Roy Halee, who made every corner of Simon and Garfunkel’s work in the studio sparkle.

Accepting the Record of the Year award with Simon, Garfunkel looked uncomfortable as he leaned into the microphone to utter a couple of words, indecipherable under the assault of the Academy’s blaring orchestra. Simon didn’t even attempt to speak.

Few in the audience knew that Simon had already decided he was done recording with Garfunkel, and was eager to launch a solo career. He’d met months before with Clive Davis, the head of Columbia Records, to bluntly give him the bad news. As Simon told his biographer Robert Hilburn, “He said he was looking forward to our next album and, in the course of the meeting, asked when we were planning to record it, and I said, ‘We’re not.’”

For his part, Davis recalls, “I told him frankly during our meeting in the office that I thought it was a major mistake. I told him how much I respected him as an artist, but I also pointed out how few musicians from best-selling groups were able to do even remotely as well on their own.” By the time of the Grammy telecast, Halee was on board, but he too had fears: “The pressure on [Simon] was enormous when he worked on the first solo album.”

As far back as 1967, while working on the Bookends album, Simon was articulating his ornery perfectionism, looking beyond Simon and Garfunkel. As he told journalist Pete Johnson, “Our fourth album, which I have been working on at a very slow pace, may be our last. I don’t believe in succeeding at something over a long period of time.”

Simon had actually recorded a rather rudimentary solo album in 1965 while he was playing shows in England, having gone overseas thinking that the failure of Simon and Garfunkel’s debut, Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., meant the two wouldn’t continue together. The Paul Simon Songbook disc was released only in England at the time, before producer Tom Wilson overdubbed electric instruments on the spare S&G recording of “The Sound of Silence,” a track from Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., without permission from either member of the duo. Wilson created a massive American hit single, causing Simon to rush back to America to reconnect with Garfunkel.

By 1971, Simon had already shown a considerable interest in music from around the world, which he’d incorporated into some of S&G’s most ambitious tracks. In 1970, he served as one of the judges at the Fifth International Popular Song Festival in Rio de Janeiro, when songwriter Jimmy Webb pulled out at the last minute, and immersed in the unusual sounds he heard there. He later told Rolling Stone, “The amazing thing is that this country is so provincial. Americans know American music. You go to France, they know a lot of kinds of music. You go to Japan, and they know a lot of indigenous music. But Americans almost never get into other sounds.”

At sessions in Columbia’s new recording studios in San Francisco, Simon completed nothing, despite the top-notch musicians gathered. Disappointed and fighting writer’s block, he returned to New York, where he had dinner at a favorite spot, the Say Eng Look restaurant. He noticed a chicken and egg dish on the menu called “Mother and Child Reunion.” It’d make a great song title, but what could the lyrics be about?

Simon was already interested in ska, the highly rhythmic music coming out of Jamaica, without fully realizing it had developed into a new genre called reggae. Jimmy Cliff’s 1970 record “Vietnam” suggested a direction for Simon’s own music. Acting on impulse, he contacted Cliff’s producer Leslie Kong, and flew to Kingston, Jamaica, with Halee to record at Dynamic Sound. Simon had no lyrics, but he cut a powerful backing track with six local players, including Hux Brown on lead guitar, drummer Winston Grennan, organist Neville Hinds and bassist Jackie Jackson.

Larry Knechtel’s piano and a four-woman chorus were overdubbed in New York, where Simon finally worked up a spectacular, and mysterious, set of verses, and a super-catchy chorus: “No I would not give you false hope/On this strange and mournful day/But the mother and child reunion/Is only a motion away.” It became the first single from his eponymous LP, reaching #4 in Billboard, immediately powering the album, released January 24, 1972, into the top five on the album chart.

The Andean folk group Los Incas, who had shone on Simon and Garfunkel’s “El Condor Pasa,” appear on the next cut, “Duncan,” which was recorded in Paris. With Simon’s acoustic guitar, the lute-like charango played by Jorge Milchberg and quena flutes from Olivier Milchberg and Juan Dalera, it’s an utterly charming and melodic five minutes. As with every other track on the LP, Halee places Simon’s voice in a clear, intimate space among the instruments, drawing in the listener without any need for histrionics or studio tricks.

Simon’s a genius with opening lines, and “Duncan” is no exception: “Couple in the next room/Bound to win a prize/They’ve been going at it all night long.” As he explained to Hilburn, “One of the things about ‘Duncan’ is it has a false beginning. I’m talking about a couple in the next room, but they have nothing to do with the rest of the song. Normally, you might go back and change it, but I thought it was interesting. It’s like that Preston Sturges film The Great McGinty, where it opens with these two guys in a fight in a bar, and it spills out into the street just when the main character in the film walks by.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years

“Everything Put Together Falls Apart” is only two minutes long, with just Knechtel and Simon accompanying the close-miked vocal, but the structure of continual modulation is complex. The title might come from the poet Yeats’ lines “everything falls apart/the center cannot hold.” Is Simon giving advice to a friend or to himself?: “Watch what you’re doing/Taking downs to get off to sleep/And ups to start you on your way/After a while they’ll change your style/I see it happening every day.”

“Run That Body Down” is like a part two for those sentiments, handled in a peppier style and with numerous totally organic vocal effects, including terrific falsetto. The lyrics specifically name Paul and his wife Peg, but whatever problem there is in the marriage—“What’s wrong, sweet boy, what’s wrong?”—is treated with humor and left abstract (they divorced in 1975). The renowned studio musicians David Spinozza (guitar), Ron Carter (bass), Mike Mainieri (vibes) and Hal Blaine (drums) cushion each edge. At two minutes the arrangement and melody change tack and lead into a delicately gnarly electric guitar solo from Jerry Hahn.

The first side of the original LP concludes with yet another winner, “Armistice Day,” which is full of musical experiments, including Simon’s acoustic note-bending, Airto Moreira’s percussion, more exciting Hahn electric guitar work and punchy alto and tenor saxophones from Fred Lipsius and John Schroer. What happens at 1:55 when Simon sings “Oh I’m weary of waiting” is almost avant-garde jazz, and the remaining minutes represent some of the most “out there” moments on the disc.

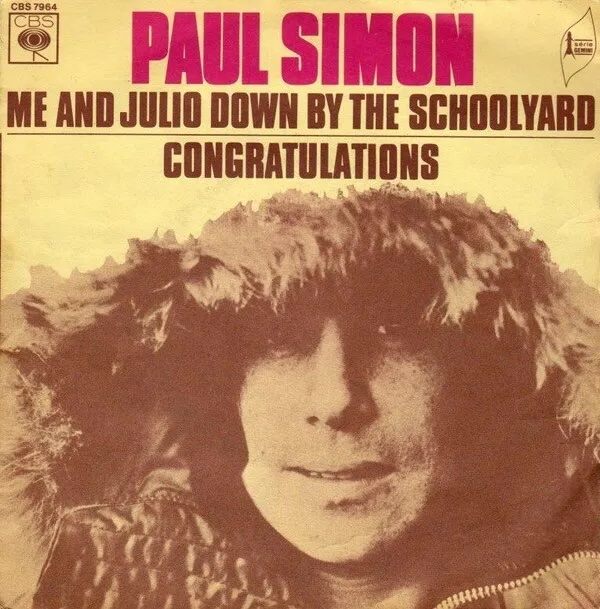

The second hit single from the set, “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard,” leads off the next LP side. The accompaniment is minimal but sounds expansive, with Simon and Spinozza on acoustics, Russell George playing bass and Airto providing the cuica, a friction drum often used in samba music. The track was engineered by Phil Ramone, subbing for Halee. The lyrics, which Simon once called “inscrutable doggerel,” don’t even need to make sense when the compulsion to sing along is so strong: “It’s against the law/What the mama saw.” When asked by Rolling Stone’s Jon Landau to explain, Simon said, “I have no idea what it is. Something sexual is what I imagine, but when I say ‘something,’ I never bothered to figure out what it was. Didn’t make any difference to me.”

As good as the rest of side two is, it really can’t live up to the perfection of side one. “Peace Like a River” is half melancholy and half defiant, perhaps the most overtly political song on the album: “You can beat us with wires/You can beat us with chains/You can run out your rules/But you know you can’t outrun the history train.” It also has some terrific guitar playing from Simon, with one riff indicating he might have been listening to Jerry Garcia’s work on “New Speedway Boogie.”

“Papa Hobo,” “Hobo’s Blues” (an instrumental recorded in Paris with violinist Stephane Grappelli) and “Paranoia Blues” (a showcase for blues bottleneck guitarist Stefan Grossman), form a brief suite of tunes that share DNA.

“Congratulations,” with Joe Osborn on bass, Blaine on drums and Knechtel outstanding on both piano and organ, is a perfect goodbye, arguing “Love is not a game/Love is not a toy/Love’s no romance/Love will do you in” before asking a question that perhaps cannot be answered by any Paul Simon narrator, “Can a man and a woman/Live together in peace?”

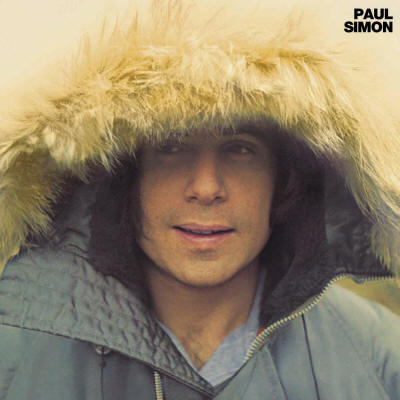

Simon is still one of the most respected and successful songwriters and performers in the world, with numerous massively important albums to his credit, but the affection many fans have for Paul Simon, released at the start of 1972 and reaching #4 in the U.S., is deep. It showed that Simon’s creativity would not be held back, no matter who he worked with. When the album was released, he told writer Don Heckman, “I am really happy to be by myself now and not have to share decisions. Now I do things almost entirely to my taste. That’s not to say I don’t listen to other opinions, but my new record is probably the most accurate one I’ve made, in the sense that it sounds the way I want it to sound.”

Simon’s recordings are available here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Simon perform “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard” in Hyde Park, London

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI was a high schooler in 1971-1972. While I considered American Pie to be the song that closed out 1971 on a depressing note (“the day the music died”), it was significant that 1972 opened with the more optimistic Mother and Child Reunion (“I would not give you false hope”). Meant a lot to me, anyway.