In the first part of our chat with Robert Hilburn, author of Paul Simon: The Life, we discussed the Simon & Garfunkel years and Hilburn’s working relationship with Simon during the writing of the book. In this second and final part, he talks about Simon’s value as a songwriter and why Simon is one artist whose work will stand the test of time.

In the first part of our chat with Robert Hilburn, author of Paul Simon: The Life, we discussed the Simon & Garfunkel years and Hilburn’s working relationship with Simon during the writing of the book. In this second and final part, he talks about Simon’s value as a songwriter and why Simon is one artist whose work will stand the test of time.

Best Classic Bands: Simon has been accused of what we now call “cultural appropriation” during the making of Graceland and some of his other works. Was it difficult for you to balance the charges against him with Simon’s own denials that he wronged anyone?

Robert Hilburn: I spent a lot of time researching the debate, both speaking to people on both sides of the issue and reading a ton of material on the Internet. To Paul, there were two issues. One was playing Sun City, the resort that was designed by the South African apartheid regime to make South Africa appear more attractive and civil. Paul and Art were offered millions of dollars to play there and they refused. He felt it was wrong. But he didn’t see going to South Africa to record with South African musicians as contributing in any way to the apartheid regime. He is still comfortable with his decision. I felt it essential to devote a lot of space to the issue, but there was no way I could resolve the charges. If anyone wants to explore them, the Internet is waiting. I do, however, think history has upheld Paul’s decision.

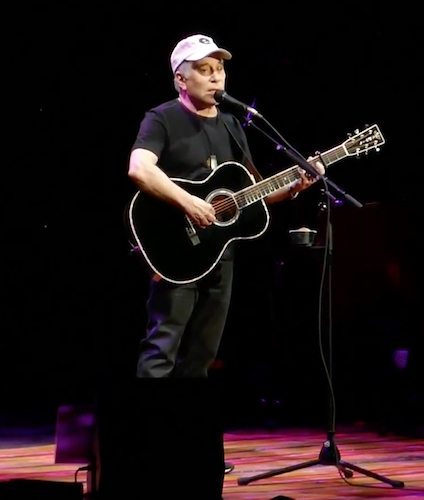

Watch Paul Simon perform the title track from Graceland

What new appreciations did you gain about the artist and his work from your experience writing this book?

Though there has been endless speculation over why Paul left Simon & Garfunkel (from ego problems to creative differences), I think it is clear the main reason he left was that he was too talented and ambitious an artist to continue to write songs in a folk style for Art’s voice. He was in fact tired of that style by 1970. He had to move on—following his father’s urging to keep moving forward—if he was going to avoid stagnation. His writing always begins with the music (not words) and he wanted to keep exploring other musical styles, including Latin, pop and world music, because that was the only way to keep inspired. The fact he was willing to step away from the Simon & Garfunkel commercial security is one sign of his value and uniqueness, the willingness to go to South Africa (a massively uncommercial move at the time) was another sign of his dedication to music, not career.

You’ve covered hundreds of other major artists throughout your long career as a music journalist, several others in book-length works. Where would you place Paul Simon among that pantheon?

You’ve covered hundreds of other major artists throughout your long career as a music journalist, several others in book-length works. Where would you place Paul Simon among that pantheon?

He stands out because of his songwriting. Unlike most of the songwriters of the rock era, he’s not just a wordsmith. He works just as hard at coming up with original music as with thoughtful and original lyrics. If one only considered the songs he wrote in the 1960s (“The Sound of Silence” to “Bridge Over Troubled Water”), he would be considered one of the great American songwriters. If you only considered the songs he wrote in the 1970s (“American Tune” to “Still Crazy After All These Years”), he’d rank as one of the all-time greats. If you only considered the songs from the 1980s and 1990s (from “Graceland” to “The Obvious Child”), he would be on that list. When you add them all together and throw in the songs he was written in the 2000s (from “Darling Lorraine” to “Questions for the Angels”), he would be way, way up on that list—not just with Dylan in the rock era, but with Cole Porter and the Gershwins in the Great American Songbook era.

Why do you feel he has been able to grow and thrive artistically while others flamed out and/or sank into becoming oldies acts regurgitating their hits?

The fact nothing has become for him more important than the music—not the fame, not the money, not the drugs, not laziness, not fear of failure. Simon understood the music is what mattered, and he knew he had to keep moving forward to keep making good music. All that is what has made his body of work strong, beginning to end.

Related: Our review of Simon/’s Stranger to Stranger album

Are there any other artists you would consider devoting this much time and effort to? That’s a good question because when I thought about writing books, I thought there would be dozens and dozens of possible subjects. In truth, I find there are remarkably few that I ended up thinking about seriously. First, I want a subject interesting for me to spend two or three years thinking about. Then, I want the subject to be significant; someone who will still be important 40 to 50 years from now, and it’s the songs that will put Paul in that class. Finally, you want someone that will let you into their life, either the artist himself as in Paul’s case or the estate as in Johnny Cash’s case. It’s like writing about some house for Architectural Digest. You don’t want to be across the street, imagining what is in the house. You want to be able to step inside and know as much as you can about what’s inside.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationSimon going to South Africa was the right thing to do. He was clearly against the apartheid regime, and he gave the racist government no support in any way. He went there to make beautiful music with great musicians who deserved to be heard.

Simon paid them well, took them many of them on tour and helped shine a spotlight on what was happening in South Africa. Here’s a case where music spoke louder than words. I can appreciate what people like Little Steven were doing to fight apartheid, but I really think that Simon, by bringing this music to the world, did more to open people’s eyes to South Africa than the “Sun City” project ever did.

That does not mean, however, that Simon hasn’t pulled some real “dick moves” over the years. I wish you guys had asked Hilburn about Paul more or less stealing the tape that led him to South Africa, and then cutting off the woman (Heidi Berg) who gave him the tape. She got no credit, or money for any of that.

And then there’s Los Lobos, and Rockin’ Dopsie & The Twisters, both of whom Paul screwed over by not crediting them for the music they created on Graceland. Then again, he did the same thing more than a decade earlier when he worked with “The Swampers” in Muscle Shoals. They came up with the riffs he was looking for, and he didn’t credit them either.

And, of course, before that he took the arrangement of “Scarborough Fair” from British folkie Martin Carthy. They eventually made up, but still.

It’s a definite pattern of behavior for Simon, and that should’ve been discussed in the interview. I wonder if Hilburn covers any of it in his book.

Agreed.