Neil Young’s reputation as a maverick was established when he abandoned the mellow country-rock glow of 1972’s chart-topping Harvest and “headed for the ditch” of more harrowing personal music. Yet that risky impulse to explore the darker visions wasn’t the first time the mercurial singer, songwriter and guitarist veered sharply from his career path. He’d already done that. Twice.

Neil Young’s reputation as a maverick was established when he abandoned the mellow country-rock glow of 1972’s chart-topping Harvest and “headed for the ditch” of more harrowing personal music. Yet that risky impulse to explore the darker visions wasn’t the first time the mercurial singer, songwriter and guitarist veered sharply from his career path. He’d already done that. Twice.

First, he exited the band he’d co-founded, Buffalo Springfield, just as the seminal L.A. quintet was poised to break through to broader acceptance. Then he signed a major label deal and released an ambitious solo album, only to change direction within weeks of its release.

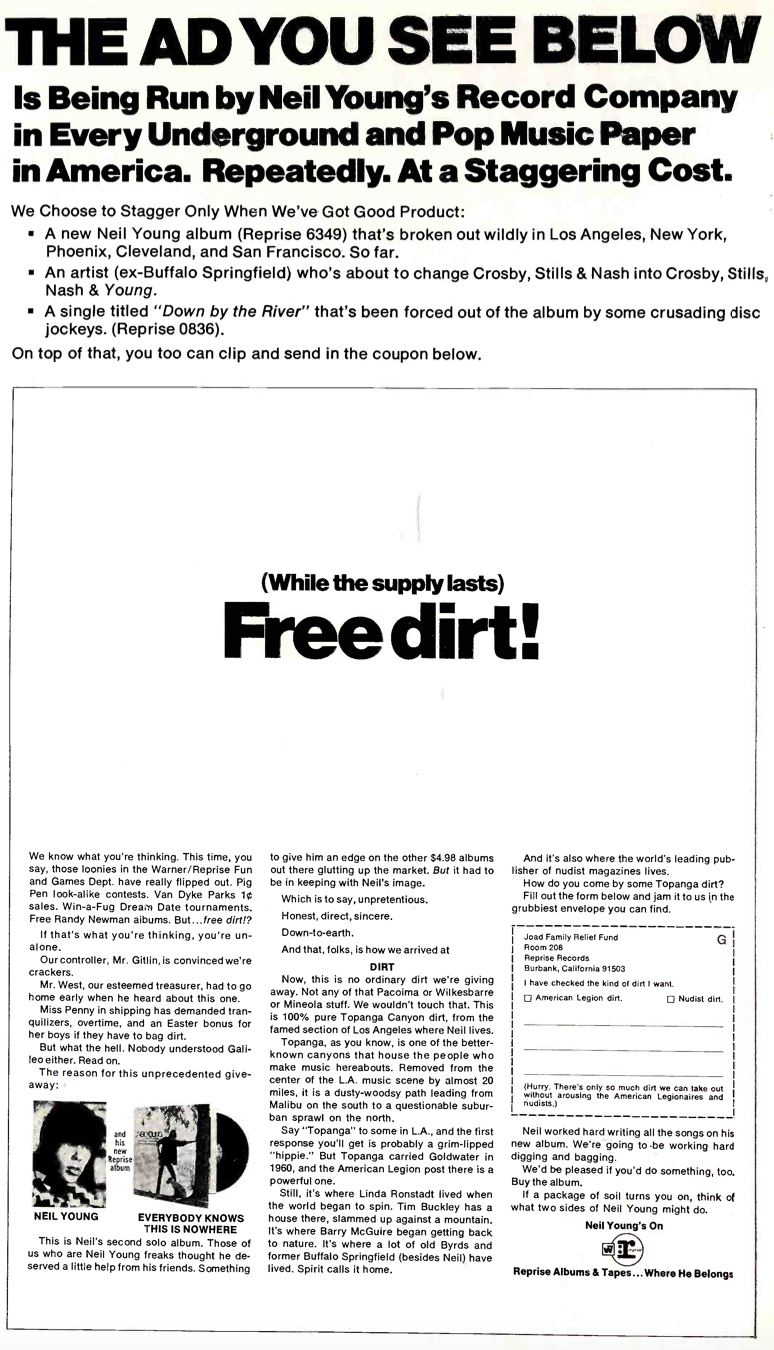

Neil Young had been inspired and influenced by the Canadian rocker’s ambitious studio collaboration with seasoned producer, arranger and songwriter Jack Nitzsche on two tracks for Buffalo Springfield Again, essentially true solo projects with Young assisted by studio players, reinforcing Young’s resolve to strike out on his own. Nitzsche committed to pitching in on several tracks for Young’s Reprise debut, which found the artist layering his own guitar and keyboard parts in league with session musicians. By the time Young and co-producer David Briggs had finished the new LP, however, they harbored second thoughts about the album’s studio polish and scattered styles. Ultimately, Young would deride the finished LP as “overdubbed rather than played.”

His dissatisfaction with the debut surfaced soon after its troubled release on Nov. 12, 1968, his 23rd birthday. A new master encoding system muddied the LP’s sound, burying Young’s vocals, prompting a remix as well as modified cover art. By the time copies of the remixed first album were released on Jan. 22, 1969, Young was already in the studio with a new band culled from the Rockets, a struggling six-piece band whose lone album had gone largely unnoticed a year earlier.

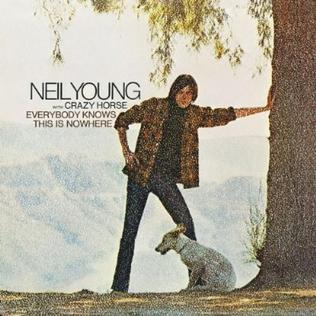

Young was attracted to the band during long, stoned jams, reveling in a hazy camaraderie that was a welcomed contrast to the “lonely” atmosphere of the protracted studio sessions for his first album. Originally based in the Bay Area, the Rockets mingled blues, folk and psychedelia, with Young drawn to core members Danny Whitten, Billy Talbot and Ralph Molina, who had graduated from doo-wop to rock. Whitten was a strong singer and solid rhythm guitarist but the rhythm section of bassist Talbot and drummer Molina was embryonic at best, closer to a garage band than the session players Young could have hired. What their foursquare foundation lacked in finesse was made up in sturdiness, however, and their street-corner harmonies translated to solid backing vocals that complemented Young’s deceptively thin but melodically precise voice. Young christened the new outfit Crazy Horse, formalizing what would become his most constant and enduring ensemble. That the quartet quickly coalesced was borne out by the new album’s swift creation, cut essentially live over the space of two weeks, the first in January, the second in March, with Everybody Knows This is Nowhere hitting stores on May 14, 1969.

The “less is more” directness of Young’s work with Crazy Horse opens the full-length from the opening riff of “Cinnamon Girl,” which typifies the marching, mid-tempo pace that would become a sweet spot for the band over ensuing decades, as well as Young’s skill at unleashing blunt force, single-note solos. These sessions marked the debut for “Old Black,” the crudely repainted 1953 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop guitar that would become Young’s go-to axe for full-throttle electric performances.

Meanwhile, the song is one of four album tracks that he wrote in a single day while grappling with a fever of 103 degrees—a quartet of songs that are now widely accepted as the album’s cornerstones, all of them now concert standbys. The song used the same D modal tuning Young had explored on “Mr. Soul,” achieving a mesmerizing drone that would become a common denominator for much of the Young/Crazy Horse canon.

“Cinnamon Girl” was right-sized for single release, casting its spell while clocking in at a few seconds under three minutes, buoyed by Whitten’s vocal harmonies. The sunnier title track, another of the songs that emerged during that feverish burst of creation, displayed Young’s comfort with older country shuffles in a bucolic ode to homesickness and the wish to escape from “this day-to-day running around.”

In contrast to those concise songs, the two other Young fever dreams unfolded as just that—like “Cinnamon Girl,” rooted in an open-ended drone, but untethered in length and ripe for jamming. “Down by the River” was a minor-keyed rock ’n’ roll murder ballad, freighted with menace. Although Young would later insist its violence was symbolic rather than actual, its titular confession (“Down by the river, I shot my baby…”) certainly sounded literal enough.

Running over nine minutes on its album recording, the song was spliced together from a much longer live take that anticipated its future as a vehicle for epic jams that showcased Young’s ferocious power wielding “Old Black.” On the choruses, the three Crazy Horse members’ vocal harmonies offset the loose immediacy of the instrumental work.

The album’s other sonic big gulp, “Cowgirl in the Sand,” was another fever-induced jam running over 10 minutes, stalking a mid-tempo shuffle with broad spaces for Young and Whitten to trade off guitar parts. Young’s stabbing, squealing solo phrases provide the track’s fireworks, but Young would cite Whitten’s deceptively economic fills as masterful in their tension and subtle variations. Like much of the album’s material, the song is something of a lyrical stew, its imagery arguably random if consistent with Young’s own claims of welcoming streams of consciousness into his wordplay.

All up, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere offered listeners just seven tracks, but its two side-closing jams more than satisfied fans. The album’s streamlined band sound offered a direct connection to Young’s emerging power as a live musician. More crucially, the partnership provided a reliable default from Young’s shapeshifting experiments through a timeless rock attack that inform Young’s ’90s reappraisal as a “godfather of grunge.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of CSNY’s Déjà Vu, released less than one year later

Young’s gain was the Rockets’ loss, however, marking the second time the Canadian rocker’s single-minded focus led to the dissolution of a band. Although he would later insist Molina, Talbot and Whitten were free to play with their old band, Young still regarded Crazy Horse as his, with his touring hastening the Rockets’ collapse. Danny Whitten’s 1972 death from a drug overdose would prove both traumatic and inspiring for Young, shaping Tonight’s the Night, a de facto eulogy for Whitten, as well as his dark “ditch” trilogy overall. Crazy Horse would rise again in 1975 with the arrival of guitarist Frank Sampedro, enabling Crazy Horse to ride again periodically ever since, whenever its restless leader chooses to saddle up.

[The album ultimately peaked on the chart at #34 more than a year later, and was certified Gold by the RIAA on Oct. 16, 1970.]

Watch Neil Young and Crazy Horse perform “Down by the River” live at Farm Aid in 1994

Related: Our 2024 review of Neil Young & Crazy Horse in concert

Young’s extensive recording library—including many box sets—is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. Tickets to see Neil Young are available here and here.

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNeil and Crazy Horse is the first jam band. I’ve been to a ton of shows from rust never sleeps to Greenday and loved every show. But Cray horse with Neil is what I love. I’m Old and creeky but when there in town I can dance. Thanks for the forum.

While I truly I love the majority of Neil Young’s various forms of music, and have been knocked out seeing him live, I would honestly hate to be tethered to the wildly inconsistent schizophrenic behavior of the man as a musical partner, or as a member of his band.