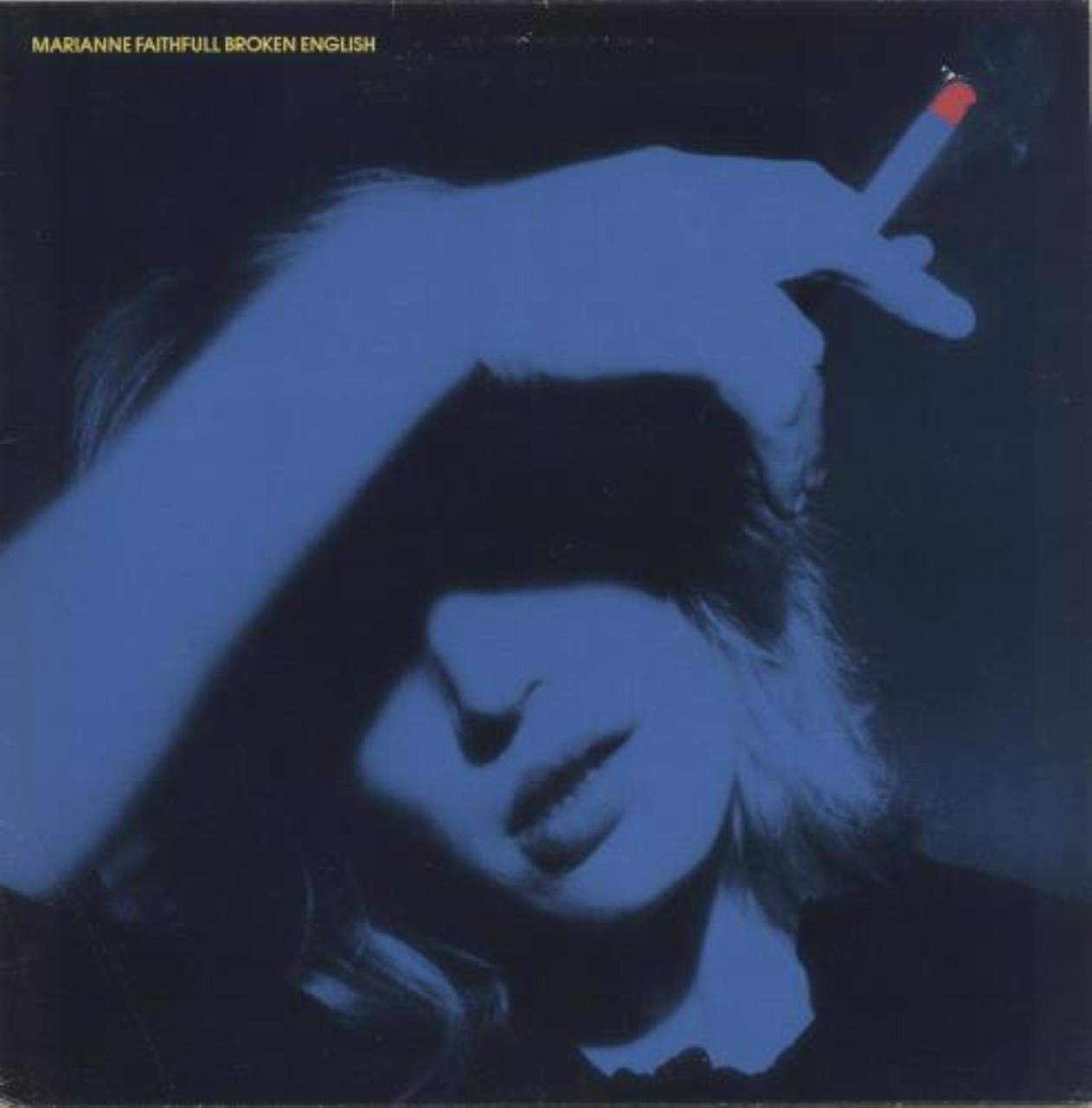

In 1979, Marianne Faithfull, if remembered at all, was probably more notorious as a personality than famous as a musician. Despite scoring hit records in the mid-’60s with tunes like Jackie DeShannon’s “Come and Stay With Me,” John D. Loudermilk’s “This Little Bird,” “Summer Nights” (by Brian Thomas Henderson and Liza Strike) and, most notably, one of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ earliest compositions “As Tears Go By,” Faithfull’s subsequent recordings hadn’t bothered the U.S. or British charts in a dozen years.

In 1979, Marianne Faithfull, if remembered at all, was probably more notorious as a personality than famous as a musician. Despite scoring hit records in the mid-’60s with tunes like Jackie DeShannon’s “Come and Stay With Me,” John D. Loudermilk’s “This Little Bird,” “Summer Nights” (by Brian Thomas Henderson and Liza Strike) and, most notably, one of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ earliest compositions “As Tears Go By,” Faithfull’s subsequent recordings hadn’t bothered the U.S. or British charts in a dozen years.

As writer Charles Shaar Murray put it in the New Musical Express that year, “She was a teenage beauty, a convent-schooled folkie, the prototype of the Rock Old Lady, the prototype of the Rock Wronged Woman, an actress of acknowledged ability who despite it all never collected the big jackpot…A life that doubtless reads better than it lives.”

Her 1994 autobiography gives the gory details, from good and bad luck to artistic peaks and self-sabotage. As Faithfull told journalist Kris Needs in Zigzag, in the ’60s, “I was just cheesecake, really, terribly depressing. It wasn’t depressing when I was 18, but it got depressing when I got older because you’re a person just like anyone else, even if you are a woman.”

Broken English, Faithfull’s 1979 album on the Island label, revealed that her voice had been damaged by years of excess and strain, with cigarettes, whiskey, downers and heroin transforming a trilling, feminine soprano into a lower growl, sometimes slightly off-key, with gaps in the phrasing. Yet she retained a nakedly pleading directness, a knack for communicating pain and wonder. With a more limited vocal range, her performances could still be mesmerizing, in a chanteuse mode that combined elements of Marlene Dietrich, David Bowie, Patti Smith and Jacques Brel.

The material and musical arrangements on Broken English show the influence of punk, reggae and jazz, and the lyrics often flowed from her still-in-process romantic and artistic collaborations, including with new husband Ben Brierly, the inexperienced producer Mark Miller Mundy, and a batch of musicians relatively fresh to her circle, including guitarist Barry Reynolds, drummer Terry Stannard and Steve York on bass.

In Interview magazine, she told Glenn O’Brien the new songs began as a sort of con job: “First of all I needed some money, so I said I had a band. I went out and got some gigs, and then I got the band, then we did the gigs, then we wrote some songs, then we did the record deal and then we made the record and here we are…It was all quite logical, rational. I need to gig so I can write. And it keeps me in shape. If I don’t go on stage I don’t keep myself in shape properly. I might gain weight, all sorts of things. I can’t write. But if you’re in a hotel room with nothing else to do, you might write.”

According to Faithfull, Mundy, who had convinced Island’s Chris Blackwell to sign her based on some demos, was lost in the studio, and Faithfull had to work things out with the core musicians (and a lot of help from Steve Winwood, an Island artist who took an interest). The summer ’79 sessions at the cheap two-year-old Matrix Studios in Bloomsbury (where the Police and the Clash had recorded) were not without conflict. Faithfull later described Mundy as “useless as a producer as well as being a flaming asshole. I was working on Broken English and Ben was off in L.A. having affairs. I was wild with jealous rage.”

Her deep emotions, almost conveyed through clenched teeth, are evident on the opening title track. She’d read a book called Hitler’s Children, about the revolutionary Baader-Meinhoff group, and connected lyrical fragments to some subtitles on a television show about Russia: “Someone came out with ‘broken English, spoken English,’ and I wrote it down because I thought it sounded so good,” she told Needs. “We were in the rehearsal studios trying to write a song and I had this in my notes, so we did that.”

The chorus of “What are you fighting for?” could be applied to Northern Ireland, Germany, the British National Front or any group of true believers, and the verses insist the singer’s not on board: “Lose your father, your husband/Your mother, your children/What are you dying for?/It’s not my reality.” Faithfull’s power under icy control is magnificent; she received her only Grammy nomination for the album (Best Rock Vocal Performance—Female) but Pat Benatar took the prize that year.

Under the hand of engineer Bob Potter, the album is sonically cohesive. Most tracks use three backing vocalists (Diane Birch, Frankie Collins and Isabella Dulaney), and several flavors of synthesizer, played by Winwood with exactly the right mix of panache and support. Morris Pert adds percussion, Daryl Way handles violin and Jim Cuomo plays saxophone when needed. Three of the album’s eight tracks, “Broken English,” “Witches’ Song” and “Why D’Ya Do It,” have writing credits for Faithfull, Reynolds, Stannard, York and co-lead session guitarist Charles “Joe” Mavety, a virtuoso who’d moved from Toronto to London a few years before. and worked with Bryan Ferry and Joe Cocker.

“Witches’ Song” follows the title track with another kind of strength. Led by lovely acoustic guitar (played by extra contributor Guy Humphries if it’s not Reynolds or Mavety), the mid-tempo bass and drums provide a solid foundation for a melodically adventurous tune, handled by Faithfull with a truly unique sound. Listen to how her voice breaks multiple times near the one-minute mark—making a virtue out of limitation and serendipity—and how the backing, ghostly voices occupy the track’s deep space.

“Brain Drain,” written by Faithfull’s husband Brierly, owes a little of its melody to Doc Pomus’ “Lonely Avenue.” It’s expertly arranged, with especially impressive multiple guitar parts and percussion, but it sounds a bit conventional after the two opening cuts, which set a high bar.

“Guilt” is written by Reynolds, and it’s outstanding. After two years of observing Faithfull as a member of her touring band, Reynolds understood how a Roman Catholic upbringing and time in a convent school had formed her. She agreed that “Guilt is one of the main things in my character.” The opening is chilling (“I feel guilt, I feel guilt/Though I know I’ve done no wrong”), and as the track cranks up, the lyrics get deeper and stranger (“I never lied to my lover/But if I did I would admit it/If I could get away with murder/I’d take my gun and I’d commit it”). There are so many great individual touches in the arrangement they can’t all be referenced, but the electric guitars are consistently thrilling, and Faithfull’s vocal might be the best she’s ever done.

“The Ballad of Lucy Jordan” is one of Shel Silverstein’s strangely jocular dark-pop songs, originally released as a single by Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show in 1974. Faithfull’s new take was a minor hit single when pulled from Broken English, with the U.K. magazine Smash Hits praising it as “an honestly outstanding offering…If you can handle this, it sounds like Dolly Parton produced by Brian Eno. Only better.” Faithfull clearly resonates with the tale of a suburban housewife and mother who suffers a mental breakdown and intends to kill herself before being “rescued” and sent to an institution. The promotional video focuses entirely on Faithfull’s still-formidable beauty and acting ability, no frills.

Faithfull explained to Needs, “We didn’t want to use a drummer, we just wanted to leave it in the air, which was very chancy because you don’t know what’s going to happen. It goes against everything you think will be alright. That’s how that happened, that’s all Stevie Winwood.” There are several synth lines, from background wash to a propulsive, burbling rhythm that could have come courtesy of Giorgio Moroder’s studio in Munich, or a Depeche Mode recording of the future.

“What’s the Hurry” is a Mavety original with an almost bubblegum-rock swing reminiscent of 10cc’s “Rubber Bullets.” It’s the album’s sore thumb. The version of John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero” that follows is maximally brilliant, and supremely odd, full of shock effects and an insistent bass line ripped from Pink Floyd’s “One of These Days.” Faithfull’s singing demands your attention, scarily authoritative as she spits out “You think you’re so clever and classless and free/But you’re still f**king peasants as far as I can see.” Set next to Lennon’s original resigned Plastic Ono Band minimalism, it’s not blasphemy to prefer the remake.

Ending the LP is “Why D’Ya Do It,” nearly seven minutes of shocking vitriol, obscenity and bile. This was the song that galvanized Mundy when he saw Faithfull play it at the Music Machine club in London in 1978. Along with “Broken English,” it enticed Blackwell into offering a deal. An interpretation and transformation of playwright-pamphleteer and Faithfull friend Heathcote Williams’ 1968 poem, it allows plenty of latitude for the singer to show her acting chops: “I really like it,” she told Needs. “I’ve done it live, and it’s great because all your fury forever can come out. It’s about sexual jealousy, it’s fury, it’s anger. Sexual jealousy can make you more furious than anything else.” The band is on fire.

Following its November 2, 1979, release, Broken English reached #57 on the U.K. album chart, and #82 in the U.S. Unfortunately, Faithfull’s highly anticipated appearance on Saturday Night Live in February 1980 turned into a train wreck when she reportedly took the dental anesthetic Procaine by mistake before her performance.

Faithfull released numerous albums, and was finally re-established as a major recording artist, in her final decades, even as she was periodically in ill health (broken hip, infections, emphysema, pneumonia, Covid). She wrote about her post-Broken English life in her book Memories, Dreams and Reflections. Her final album, a “dream project” collection of British romantic poetry (Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth) with music from Warren Ellis and Nick Cave, was released in 2021. Faithfull died on January 30, 2025, in her beloved London.

Broken English is available in the U.K. here. A boxed set, Cast Your Fate to the Wind: The Complete UK Decca Recordings, was released in 2025. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Faithfull perform the title song from Broken English live in 2005

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI’m a Stan for her less-appreciated follow-up, Dangerous Liasons – less heavy portent and more tuneful, and it’s a 5 dollar bin vinyl mainstay. Check out Strange One, Intrigue and Eye Communication.