It’s one of the most oft-quoted, and hotly debated, lyrics of the past 50 years: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” Entire web pages are devoted to its meaning. In one online chat room, a participant writes, “I always understood it to mean that the only time you’re really free to do whatever you want is when you have nothing to lose—there can’t really be consequences if there is nothing to lose.” A second person opines, “If you have nothing left to lose, you’re not tied down to anything and you’re free. You can wander around anywhere, just pick up and go like the two hobos in the song.”

It’s one of the most oft-quoted, and hotly debated, lyrics of the past 50 years: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” Entire web pages are devoted to its meaning. In one online chat room, a participant writes, “I always understood it to mean that the only time you’re really free to do whatever you want is when you have nothing to lose—there can’t really be consequences if there is nothing to lose.” A second person opines, “If you have nothing left to lose, you’re not tied down to anything and you’re free. You can wander around anywhere, just pick up and go like the two hobos in the song.”

Not everyone thought so highly of the line. Grumbled one person, “This has always struck me as one of the stupidest statements in all of pop culture.”

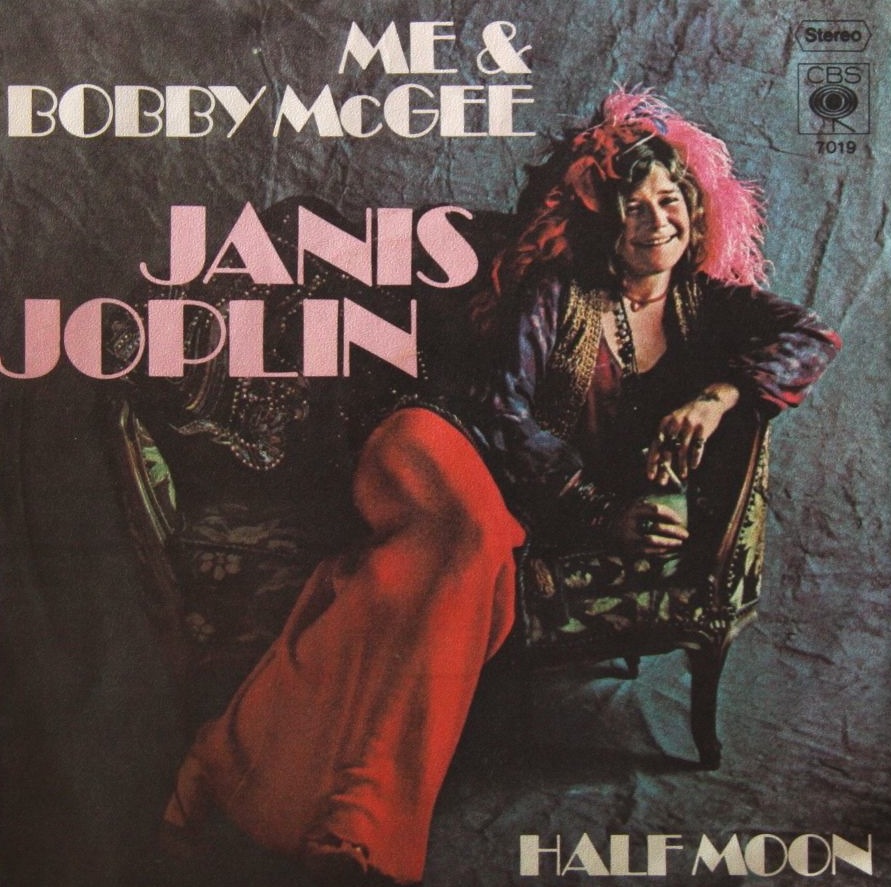

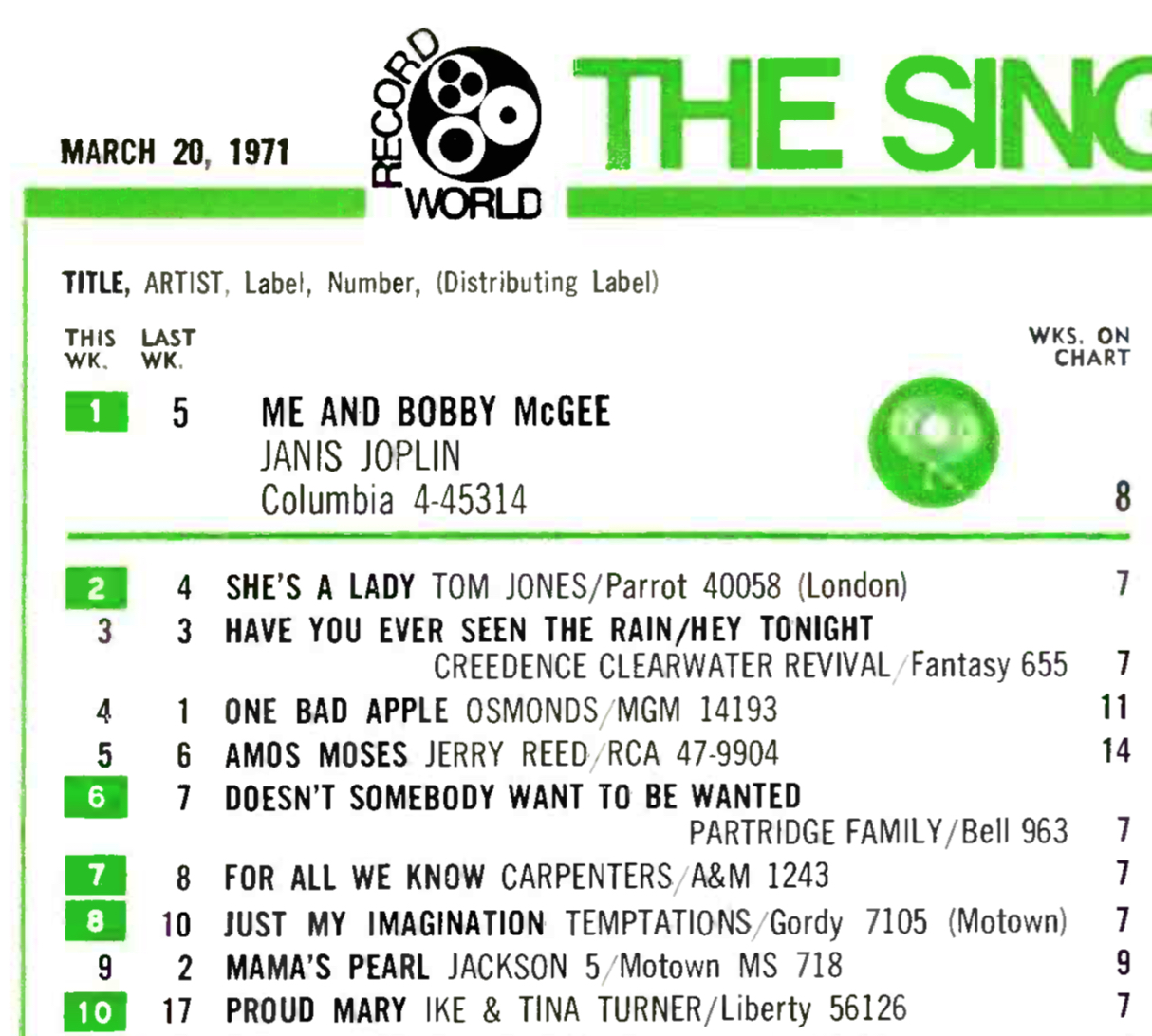

Regardless of one’s take on that key segment of the song’s chorus, most folks know “Me and Bobby McGee”—the song in which that line resides—by Janis Joplin’s version. Recorded with her new Full Tilt Boogie Band for Columbia Records just days before her death on Oct. 4, 1970, the single reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and Record World singles charts on the week ending on this date in 1971. Both the single and the album from which it was drawn, Pearl—Joplin’s final solo studio LP—first charted on January 30; the album, too, would reach #1, Joplin’s only one to do so.

The single became only the second in Billboard’s history to vault to the top of the pop chart following the artist’s death, following Otis Redding’s 1967 “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay.” The magazine ranked Joplin’s “Bobby” (backed with “Half Moon”) as the #11 single of the year 1971.

She was hardly the first artist to record the tune though. Written by Kris Kristofferson and Fred Foster, it was first recorded by country singer Roger Miller, who usually cut his own songs, clever, memorable tunes like “King of the Road” and “Dang Me” that crossed over to the pop charts and AM rock radio. Miller’s version only made #12 on the Billboard country singles chart but that was enough for it to reach the ears of other artists who chose to perform their own interpretations.

Kenny Rogers and the First Edition were the next, after Miller, to record the song, and Kristofferson himself put it on his 1970 Kristofferson album. Other early adapters included everyone from Bill Haley and the Comets to Sam the Sham! The Grateful Dead began performing the song live in November 1970, just after Joplin’s death, and in time such notables as Johnny Cash, Chet Atkins, Joan Baez and, much later on, Pink, would make it their own.

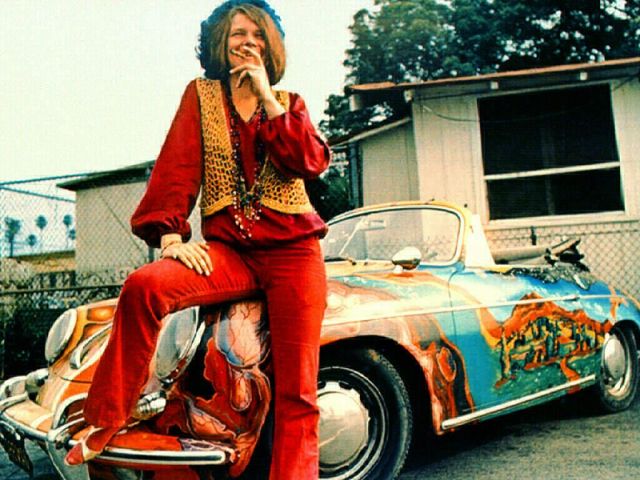

But Joplin has always owned it. She first heard the tune when Kristofferson himself sang it to her, and singer-songwriter Bob Neuwirth helped Joplin shape the arrangement she would cut. In the studio she and her band ease into the song slowly, and it then accelerates, as studio pianist Stephen Ryder takes off into a rocking solo. By the end the band is going at it so feverishly they have nowhere else to go but to suddenly stop playing and let the listener take a deep breath.

So how did “Me and Bobby McGee” come about, anyway? “The title came from [producer and Monument Records founder] Fred Foster,” Kristofferson told writer Lydia Hutchinson in Performing Songwriter magazine. “He called one night and said, ‘I’ve got a song title for you. It’s “Me and Bobby McKee.”’ I thought he said ‘McGee.’ Bobby McKee was the secretary of [songwriter] Boudleaux Bryant, who was in the same building with Fred. Then Fred says, ‘The hook is that Bobby McKee is a she. How does that grab you?’ (Laughs) I said, ‘Uh, I’ll try to write it, but I’ve never written a song on assignment.’ So it took me a while to think about.” (Foster gets half credit on the composition, presumably because it was his idea.)

Inspired by a scene in the Fellini film La Strada, Kristofferson constructed the tale. In the film, a girl shows up in town, no one knows where she is from, and she dies. “That night,” Kristofferson told Hutchinson, [lead actor Anthony] “Quinn goes to a bar and gets in a fight. He’s drunk and ends up howling at the stars on the beach. To me, that was the feeling at the end of ‘Bobby McGee.’ The two-edged sword that freedom is. He was free when he left the girl, but it destroyed him. That’s where the line ‘Freedom’s just another name for nothing left to lose’ came from.”

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

Fortunately for Joplin, Bobby is usually a male’s name, and with the switch of a few pronouns she was able to sing it without changing the name. Kristofferson first heard her version, he told Performing Songwriter, when “Paul Rothchild, her producer, asked me to stop by his office and listen to this thing she had cut. Afterwards, I walked all over L.A., just in tears. I couldn’t listen to the song without really breaking up. ‘Bobby McGee’ was the song that made the difference for me. Every time I sing it, I still think of Janis.”

Watch the official music video for Janis’ hit single version of “Me and Bobby McGee”

Related: Kristofferson died in 2024 at 88

6 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationwat een super nummer blijft dit

Thanks, Jos. English translation: “What a great song this remains.”

Such a great tune! I can’t recommend highly enough how much every person who loves Janis or just great music documentaries..should be sure to see The PBS documentary that I think is part of their American masters series called Janis: Little girl blue. All the American masters shows are really awesome..especially the BB King and Fats Domino ones..the Janis one though might be the most moving and was the only one that made me tear up each time I’ve seen it..especially towards the end. Phew it’s incredible!!

Great Info !! – thanks

There is no studio pianist named Stephen Ryder playing on Janis’ Bobby McGee. It’s pure Richard Bell on piano from beginning to end.

I know, I was at Sunset Sound that day too. That Ryder story is a completely untrue.

You didn’t mention Charlie Pride’s version of the song. I love his performance next best to Janis’.