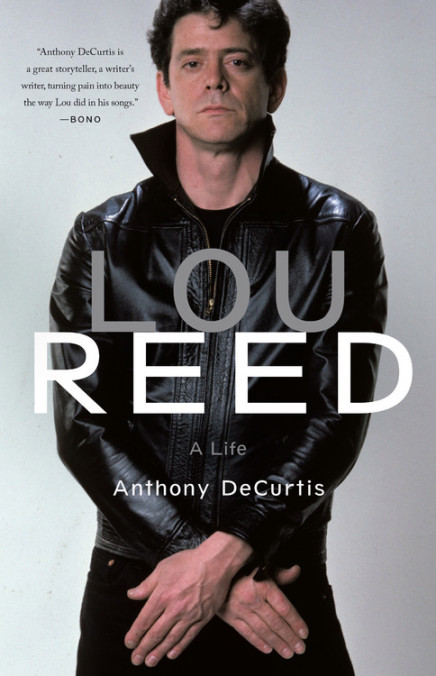

Lou Reed could be a prickly character… some people would argue that deleting everything in that statement after the “k” would be a more honest assessment. Contradictory and a natural-born contrarian—he was a hustler with a poetic soul, a damaged man who returned from the demimonde with stories that hid their compassionate heart behind a hipster’s sneer, an artist who yearned for mass acceptance but repeatedly sabotaged his own career—Lou Reed presents a handful and then some to a potential biographer. But he is lucky to have Anthony DeCurtis write A Life (Little Brown and Company), as the Rolling Stone editor and writer has written an exemplary biography, a book that can take its place on a shelf besides Peter Guaralnick’s magisterial two-volume Elvis bio, and Nick Toshes’ acidic Dino.

Lou Reed could be a prickly character… some people would argue that deleting everything in that statement after the “k” would be a more honest assessment. Contradictory and a natural-born contrarian—he was a hustler with a poetic soul, a damaged man who returned from the demimonde with stories that hid their compassionate heart behind a hipster’s sneer, an artist who yearned for mass acceptance but repeatedly sabotaged his own career—Lou Reed presents a handful and then some to a potential biographer. But he is lucky to have Anthony DeCurtis write A Life (Little Brown and Company), as the Rolling Stone editor and writer has written an exemplary biography, a book that can take its place on a shelf besides Peter Guaralnick’s magisterial two-volume Elvis bio, and Nick Toshes’ acidic Dino.

In his preface, DeCurtis (full disclosure: Anthony was my editor at Rolling Stone) writes that one of the reasons he was one of the few journalists the famously cantankerous Reed respected was because he saw Lou as Lou saw himself: a New Yorker and a writer. [Reed was born March 2, 1942, and grew up on Long Island, New York.] The Reed that inhabits this book is powerfully drawn, from moment to moment deeply appealing and appalling. You get a sense of both what it must have been like to to live both in Reed’s skin—the Oedipal rage and resentment born of his parents committing him for electroshock treatment in his teens, and how this impacted his relationships with the poet Delmore Schwartz, Andy Warhol, and even Arista head Clive Davis—and in his wake, as he sheds friends, lovers, bandmembers, management with barely a shrug. And how “Lou Reed,” the street-smart, tough talking, sexually fluid, drug fiend was both the real man and a mask; his work both a reflection and effacement.

Watch Reed perform at Farm Aid in 1985

Related: When Lou Reed met Metallica

Reed saw himself very much as part of the New York literary tradition, and the city is a constant in Reed’s life. DeCurtis, a fellow born-and-bred New Yorker, makes New York a character in his book, sketching the sketchy Meatpacking District, the carriage trade decadence of Warhol and the Factory, and the bohemian comfort of his later years. It’s a sympathetic portrait, but hardly a hagiography. You can feel DeCurtis wrestling to explain some of Reed’s worst excesses and shoddy treatment of others (“Reed likely believed that, as with Warhol, he had already gotten whatever he was going to get from Cale”), but he shows great empathy for often ignored figures such Bettye Kronstad, Reed’s first wife. While he tries a little too hard to find nice things to say about ambitious misfires such as Lulu, his 2011 collaboration with Metallica, DeCurtis is clear-eyed enough to write of Reed’s “deep romanticism, which could border on Hallmark card clichés,” and that “despite his protestations to the contrary, Reed had been thinking about his legacy from the time of the first Velvet Underground record.”

DeCurtis also has the magazine writer’s eye for a good story. He turns the story of how the Tots, a pedestrian bar band from suburban New York, were recruited as Reed’s back up into a four-page microcosm of Reed’s best and worst impulses. And when Reed runs into Keith Richards on a Caribbean vacation and asks for some marijuana, DeCurtis steps back, enjoying how the idea of “two reprobates in winter…sharing weed while on vacation says so much about the quotidian joys survival can make possible.”

Reed’s story had a happy ending. Like many a New Yorker, Reed kept kvetching until the end, but managed to find some level of comfort with Laurie Anderson, a writer and recording artist with a personality as strong as Reed’s, and they settled into their own version of domestic bliss becoming, as DeCurtis quotes Bob Neuwirth, “the Ma and Pa Kettle” of the New York underground. Reed became what New Yorkers call a “macher,” or “altacocker,” a respected member of the community. DeCurtis’ book gives Reed’s complicated, prickly life the book he deserved.

Watch Reed perform “Sweet Jane”

Reed died October 27, 2013, from liver disease at the age of 71, at his Hamptons home on Long Island.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.