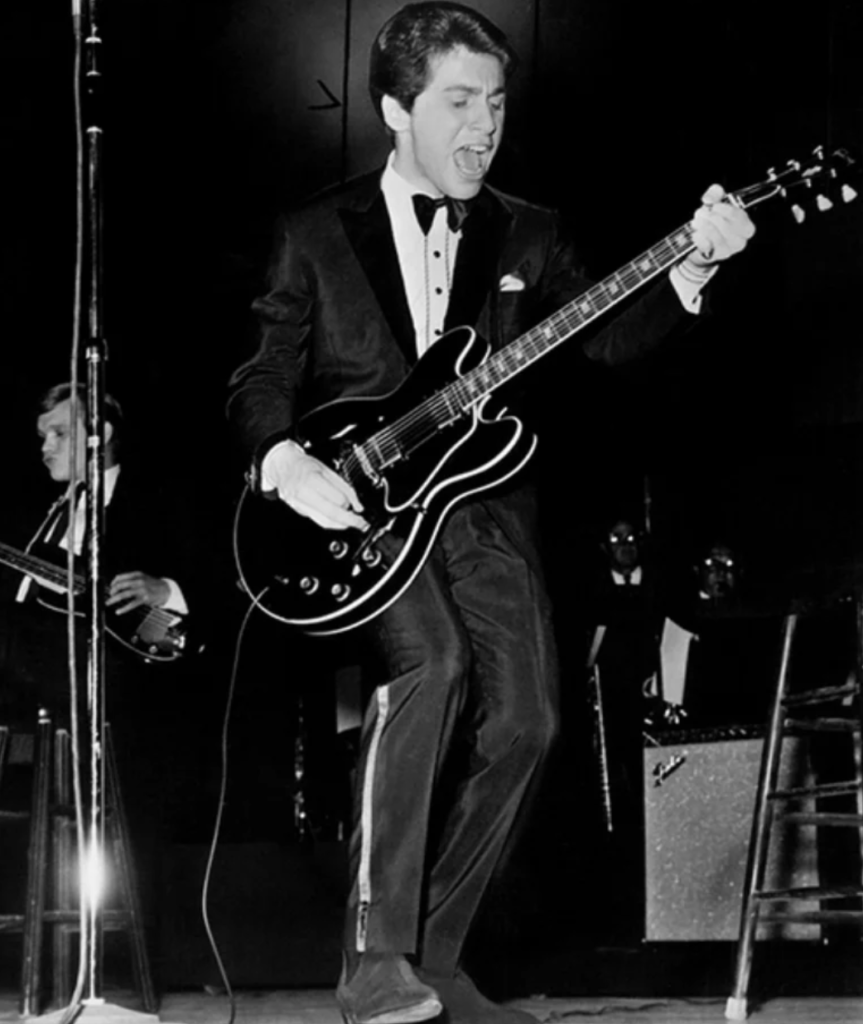

When John Henry Ramistella moved with his family from New York City to Baton Rouge, La., in the late 1940s, it put him—a precocious kid with a yen for music—in a position to soak up the special blend of jazz, blues, Afro-Caribbean rhythm and Cajun Zydeco in the area, at a time when rock and roll was still waiting in the wings. Tutored by his father and uncle, Ramistella was playing guitar well by the time he was eight, and led bands in junior and senior high school, first recording for the Suede label at the age of 14. For a time, he was in a band called the Rockets with Dick Holler, the future composer of both “Abraham, Martin and John” and “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron.”

When John Henry Ramistella moved with his family from New York City to Baton Rouge, La., in the late 1940s, it put him—a precocious kid with a yen for music—in a position to soak up the special blend of jazz, blues, Afro-Caribbean rhythm and Cajun Zydeco in the area, at a time when rock and roll was still waiting in the wings. Tutored by his father and uncle, Ramistella was playing guitar well by the time he was eight, and led bands in junior and senior high school, first recording for the Suede label at the age of 14. For a time, he was in a band called the Rockets with Dick Holler, the future composer of both “Abraham, Martin and John” and “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron.”

In a nod to the Mighty Mississippi, by the time Ramistella was 18 he’d adopted the stage name “Johnny Rivers” at the suggestion of influential DJ Alan Freed, and recorded for a number of small labels without much commercial success.

As he told writer Mike Ragogna in 2013, Rivers had seen Elvis Presley playing live as early as 1954 and saw the future emerging out of the country and western scene. Eventually, “Just like anybody else, Chuck Berry was one of the great influences, and Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Jimmy Reed…I also listened to Fats Domino, a lot of the New Orleans guys…There were so many South Louisiana guys including Slim Harpo, he was from Baton Rouge. Being a young guitar player, I always gravitated to guitar songs…back in those days in the ’50s and ’60s, there were a lot of guitar instrumental hits.”

Related: Read more about the career of Johnny Rivers here

After Hank Williams’ first wife Audrey encouraged Rivers to move to Nashville, he got work there as a songwriter and demo singer, but just about gave up on live performances. The Louisiana-born guitarist James Burton, who played with Ricky Nelson, recommended one of Rivers’ songs, “I’ll Make Believe,” to Nelson, which led Rivers to relocate to Los Angeles in 1961.

As detailed in many books, including Dominic Priore’s Riot on Sunset Strip and Erik Quisling and Austin Williams’ Straight Whisky, the L.A. nightclub scene was lively, but before the Beatles’ first recordings arrived in 1963, it was mostly a jazz and R&B scene. The club owner, Elmer Valentine, poached Rivers from a steady gig he played in a trio with bassist Joe Osborn and drummer Eddie Rubin at Gazzarri’s Italian restaurant, presenting them beginning on January 15, 1964, at a club he called Whisky a Go Go, after a Parisian discotheque he’d been to the previous year. A former bank building at 8901 Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood, it had a short-lived life as a club called the Party before Valentine renamed it.

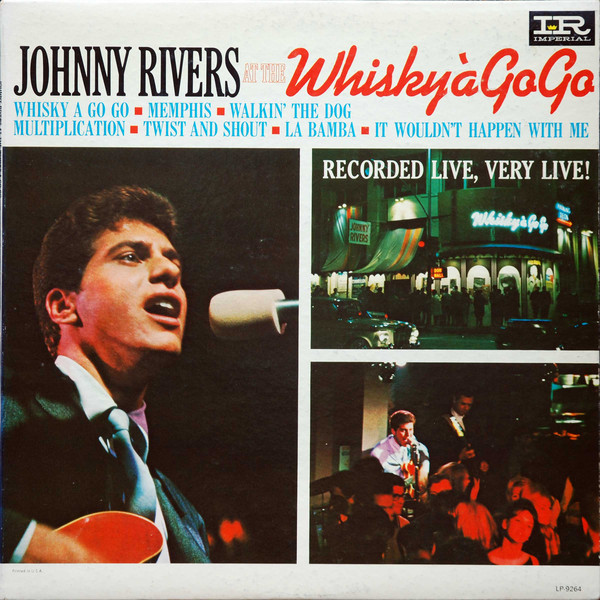

With scantily clad female dancers gyrating in cages on an elevated platform, and a set of popular hits tailor-made for celebrities and scenesters who wanted to Frug, Watusi and Shing-a-Ling the night away, Rivers and company settled in as the house band for what became a wildly successful two years. The entrepreneur Lou Adler, who’d signed Rivers to his Dunhill Productions, convinced Imperial Records to finance a quicky LP, recorded live at the Whisky on Wally Heider’s dual Ampex tape machines in a truck parked outside the club, manned by engineers Bones Howe and Harold Linstrot.

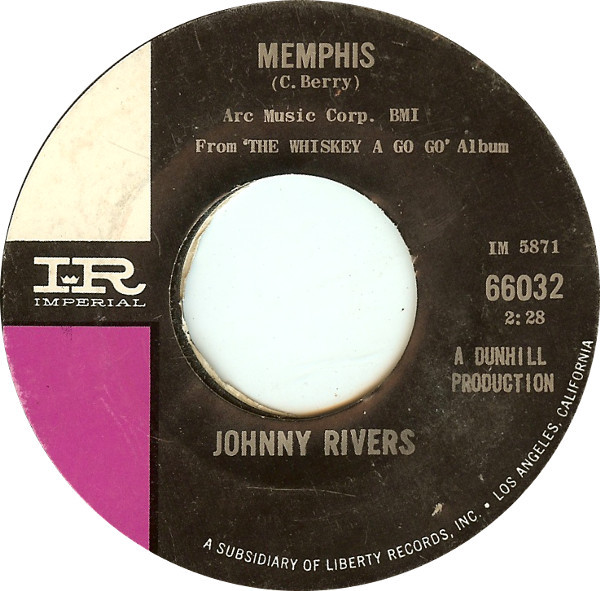

Recorded in January 1964 and (amazingly) released the next month after some studio tinkering, Johnny Rivers at the Whisky à Go Go was an immediate hit, reaching #12 in Billboard and staying on the chart for nearly a year. The 45 rpm release of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis” went to #2, kept out of the top spot by the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around.” Berry’s original 1959 version (as “Memphis, Tennessee”) was the single B-side to “Back In the U.S.A,” and hadn’t charted on its own.

“When I opened the Whisky,” Rivers told Ragogna, “No one was playing any rock and roll or blues here in L.A. The closest thing to any kind of rock and roll was the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean, so I brought that South Louisiana funky blues, stuff like that. I even used to close my set at the Whisky with a tribute to John Lee Hooker.”

The infectious and humorous “Memphis” contains plenty of crowd noise and handclaps (much of it overdubbed), and the confident, insistent tenor vocal and guitar playing that characterizes the entire set. It conveys some of the raw excitement of the Whisky dance floor in a direct, simple format, to a national audience ready to turn away at least partly from the trauma of JFK’s assassination. Just as the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan’s show, Rivers’ live album rode the wave of new, exuberant, fun rock and roll.

“It Wouldn’t Happen With Me” is a novelty number by Ray Evans that mentions Elvis, Rick Nelson and Jackie Wilson. It’s lyrically updated from Jerry Lee Lewis’ 1961 take (then titled “It Won’t Happen With Me”) to include verses about the Beatles in place of Fabian.

Don Gibson’s “Oh Lonesome Me” is done in a peppy rhythm that turns the 1958 country-pop crossover into a floor-filler, after considerable “sweetening” in the studio to add a sing-along and more whoops of delight. “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” a ripping version of Lloyd Price’s 1952 R&B hit, is one of the rawest recordings on the LP, and seems to have the least studio fiddling. It runs into a jam titled after the nightclub, based on snippets of “Baby Please Don’t Go” (inspired by the Muddy Waters version) and the Impressions’ “It’s Alright.” “Whisky à Go Go” is credited to Rivers, no doubt to give him some publishing income on an album otherwise filled with other people’s songs.

Rufus Thomas’ “Walking the Dog” has one of Rivers’ best vocals as he works the crowd, a simple but effective guitar solo two minutes in, and some groovy drumming. Another Chuck Berry B-side, “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” might have been called “Brown Skinned Handsome Man” if Berry had been able to push his racial observations a bit further. Still, he inserted plenty of social commentary along with his usual wit. The tongue-twisting lyrics are handled perfectly by Rivers: “Milo Venus was a beautiful lass/She had the world in the palm of her hand/But she lost both her arms in a wrestling match/To get a brown eyed handsome man.”

Bill Cook’s “You Can Have Her (I Don’t Want Her)” was a hit for Roy Hamilton in 1961, and Bobby Darin had minor chart success with “Multiplication” in ’62; in the hands of Rivers’ trio both sound a bit rote, just filling out the live set and keeping the dancers moving. An excellent, hip-shaking six-minute medley of “La Bamba” and “Twist and Shout” completes the LP with more than a nod to another best-selling album, Trini Lopez at PJs, which perhaps gave Adler the idea of recording Rivers at the Whisky in the first place.

Johnny Rivers recorded four additional albums at the Whisky, yielding more hit singles, including “Seventh Son” and “Secret Agent Man,” but his distinguished career as a songwriter, singer and owner of the Soul City label (home to the Fifth Dimension, Al Wilson and other hitmakers) has much more to it than his early days stoking and exploiting dance crazes and the fad for live recordings. He’s had two dozen Billboard Hot 100 entries, and excelled at everything from ballads (“Poor Side of Town”) to revived oldies (“Rockin’ Pneumonia—Boogie Woogie Flu”).

Inexplicably, he hasn’t been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Now in retirement at the age of 81, his last live performance was at Commerce Casino just south of Los Angeles in July 2023. As he said, surveying his long career, “I follow my heart and I work on projects I feel, and if it changes, that’s when I move on.”

Many of Rivers’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Rivers mime “Memphis” on American Bandstand

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe bassist playing with Rivers at the ‘Live at the Whisky a Go Go’ album, Joe Osborn, would go on to play on countless legendary recordings as part of The Wrecking Crew.

Think about some of the talent that Johnny nurtured. The 5th Dimension got its big break on the Soul City label, hitting with a song by one of Johnny’s songwriters, Jimmy Webb. What a time!

Why is this legend not in the R+R Hall? Shameful.