In the fall of 1974, Yoko Ono gave a lecture at my college, Colgate University. During my senior year, I had the unique privilege of being the only student on the college staff as Director of Video Services for the school’s Education Department. I had my own office and a full complement of the first generation of consumer video equipment that was primarily used for taping student teachers. For the rest of the year I would also tape this and that around campus. But largely, I had the Sony half-inch reel-to-reel recorders, editing equipment, cameras and Portapaks to play with.

When the Ono lecture was announced, I knew I had to do a multi-camera shoot of her speaking in the campus chapel. She had been a collaborator with video art pioneer Nam June Paik and cellist Charlotte Moorman in the piece “TV Bra for Living Sculpture,” in which Moorman had two small video monitors mounted atop her breasts as she played. It seemed utterly fitting to tape Ono as she spoke as she was a pioneer in the medium I was playing with.

There was also the not-small matter in my book that she was married to John Lennon.

About a month after my 10th birthday in January 1964, The Beatles made their American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. It changed my life, and now, 51 years later, rock ‘n’ roll remains the backbeat that drives my existence – and a substantial part of my professional career.

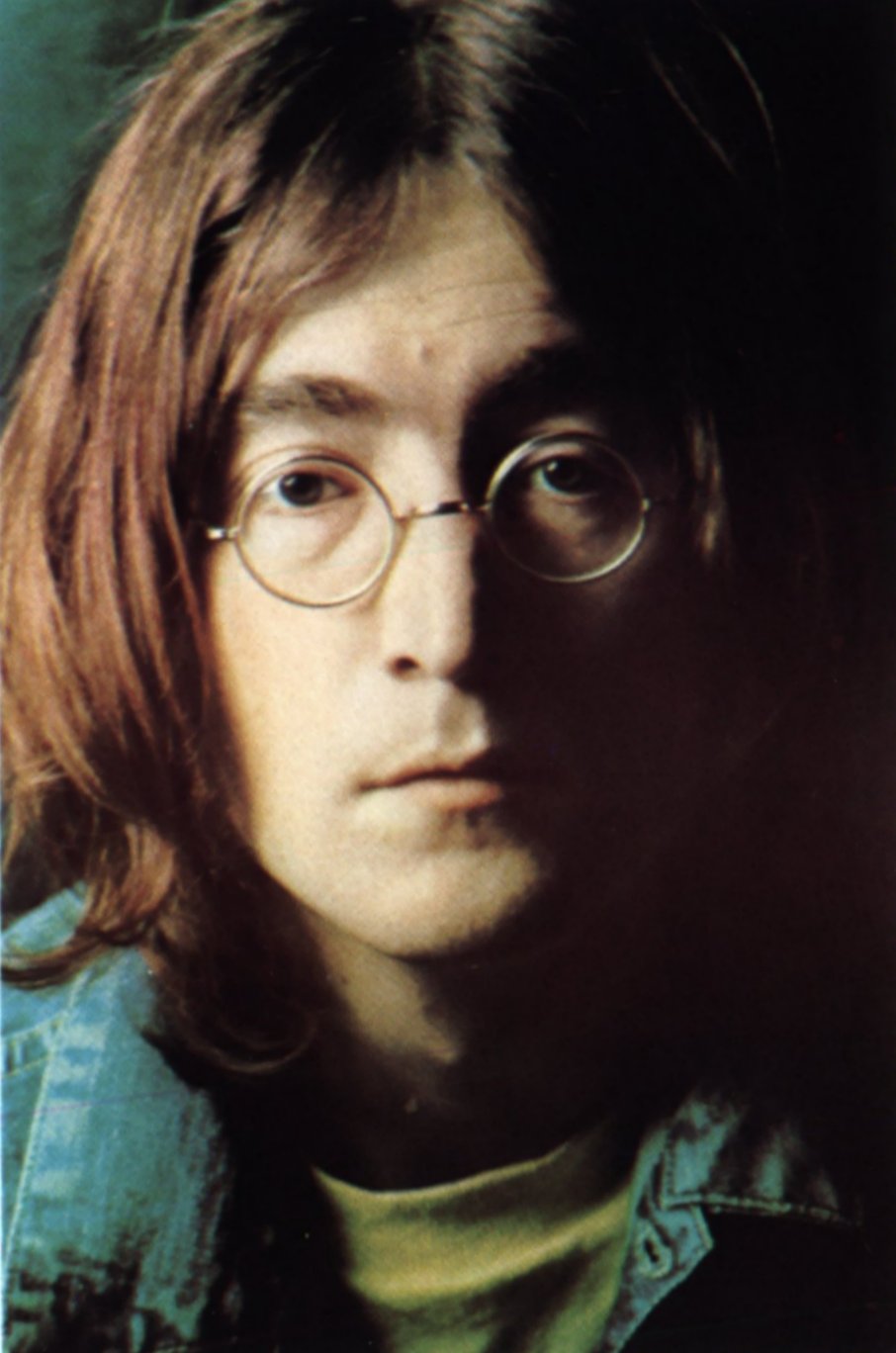

As a Beatles fan from that night on, many years later I deduced that Beatles fandom had a taxonomy. You were usually either a John-ist or a Paul-ist, though there was also a substantial George-ist minority; and of course we all simply love Ringo. I was a dedicated John-ist with secondary George-ist leanings. I loved his sardonic humor, rebelliousness and the darker tints of the Lennon/McCartney songs that were primarily his; see “We Can Work It Out” and the song’s McCartney verses and Lennon bridge for a clear example of the difference.

Four years earlier Lennon had accompanied Ono when she had an exhibit at the Everson Museum in nearby Syracuse. But unlike some of my fellow students, I wasn’t hoping he’d tag along to her lecture (though if he had I’d have been thrilled). I was genuinely interested in this woman who had captured Lennon’s heart, soul and imagination on her own terms.

I can’t recall much of anything she said to the packed house in a talk about creativity and being an artist. I was too busy fiddling with the video gear and applying my artistry and creative impulses to what we captured on tape.

Following the lecture I was approached by Yoko’s assistant (who bore the aptly au courant for the times and very memorable name of Sara Seagull). She asked if I could send them a copy of the taping and offered to pay for the tape.

I did, and a few weeks later I got a check for $15 written on the account of John Lennon, One West 72nd Street, New York, NY. It was signed by two of his accountants.

As I proudly showed it to my friends, they were mightily impressed. And most all of them insisted that I couldn’t cash it because it was from Lennon.

I found that odd. It didn’t have his signature on it. (Friends would later tell me how Ringo during that same time, living in Los Angeles, would pay for most every purchase he made with a signed personal check because they were rarely cashed, allowing him to largely shop free of charge.) I surmised that the Lennon check had probably never even passed through the Lennono home and offices at The Dakota.

I kept telling my friends as they insisted I save it: “He didn’t sign it! It was never even in his presence! Why shouldn’t I cash it?” When I finally did deposit the check (after making a photocopy I later lost), the teller’s eyes all but literally bugged out as she looked it over.

I imagine my less than obsessive feelings about even a tangential contact with massive worldwide fame and one of my true heroes helped qualify me for my later career as a popular music journalist. Sure, fame impressed me. But it has never left me gobsmacked and all wacky like too many others. After all, celebrities are still only human, pants on one leg at a time.

Not long after graduating I lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just as John and Yoko did. It was a point of pride that Lennon didn’t just live in the neighborhood but was a part of it. Sightings were common (though I never had one). It was the neighborhood way to maybe just say or wave hello, which John would do in return, but also let he and Yoko be. That was also part of being a New Yorker in the 1970s; it was uncool to gush over celebrities– they were simply part of the landscape. (The only two times I saw every head on the street turn was on Fifth Avenue in the 50s when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis walked by, and another time when I came out of a building onto Madison Avenue with Slim Whitman in his full country singer regalia at the time when his late-night TV infomercials were ubiquitous.)

Not long after graduating I lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, just as John and Yoko did. It was a point of pride that Lennon didn’t just live in the neighborhood but was a part of it. Sightings were common (though I never had one). It was the neighborhood way to maybe just say or wave hello, which John would do in return, but also let he and Yoko be. That was also part of being a New Yorker in the 1970s; it was uncool to gush over celebrities– they were simply part of the landscape. (The only two times I saw every head on the street turn was on Fifth Avenue in the 50s when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis walked by, and another time when I came out of a building onto Madison Avenue with Slim Whitman in his full country singer regalia at the time when his late-night TV infomercials were ubiquitous.)

When an Esquire cover story on Lennon came out in 1980 that detailed his riches and tried to slime him, the writer of “Working Class Hero,” as a wealthy hypocrite who had betrayed his revolutionary values, I didn’t buy into the theme; in fact, it ticked me off. Lennon had already given us far enough. He’d been near broke in the early days of The Beatles’ Apple venture. Ono was shrewd enough with money to make her and John very wealthy (and, as I knew, they paid their bills promptly). Good for him, was my thought.

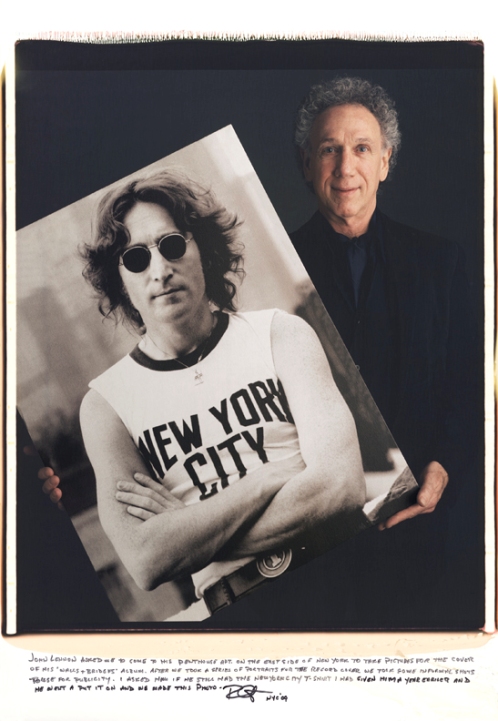

Photographer Bob Gruen with his photo of John Lennon he also gave me.

In the mid 1980s I would have a brush with Ono yet again when I helped mount and promote an exhibit by famed music photographer Bob Gruen, who had taken such iconic images of Lennon as the shot of him flashing the peace sign before the Statue of Liberty after he’d prevailed over efforts to deport him and got his green card. Ono attended with Sean, their son. As thanks for working on the show, Bob gave me a signed poster of John from a previous exhibit – the famed shot of Lennon on the rooftop of the Record Plant recording studio in his New York City t-shirt.

Related: Our (rare) interview with Yoko Ono

It was pinned to the wall of my office just above my desk for most all of the rest of my New York City years. After I moved to Austin, TX it spent many years on the wall beside my bed. Lennon was a integral part of my New York experience even if I never encountered him there. The city where he found a home became my spiritual hometown rather than the upstate burg where I was born and grew up – a city in those heady times that was broke and crime-ridden, yet the vibrant center of the creative and cultural universe. It was where I became who I am. And where John Lennon could be an ex-Beatle without being excessively bothered as he was during most all of the years of Bealtemania. It was a city where we could be free to be ourselves.

Related: A Beatle fan’s memorable meeting with John Lennon

Now, decades after he was so senselessly slain, Lennon still means so much to me. And I still do not regret cashing that check. I often describe my politics as (Groucho) Marxist/(John) Lennonist, as much in seriousness as a clever quip. I have also concluded in the sort of definitive rating I try to resist in talking and writing about and opining on music that – in addition to all his many other musical, artistic and cultural achievements – he’s the greatest rhythm guitarist that rock ‘n’ roll has ever seen. That may sound like damned with faint praise… but since rock ‘n’ roll is in the end all about the rhythm and the groove, it puts Lennon atop the very core of the dynamic force that has energized my life.

My last encounter with Yoko was a phone interview with her in the early 1990s about the Bag One touring exhibit of Lennon’s artwork. Twice during our talk, she said to me: “You must have really loved John because you know so much about him.” Blow me away with a feather….

Yes, Yoko, I loved him dearly. I loved him because he was real. I loved him because he was the embodiment of all that I love about rock ‘n’ roll. I loved him because he was an idealist who held onto the best values of the late 1960s counter-cultural revolution, yet was also all too human with his many warts, foibles and even seeming hypocrisies.

Loved him so much and appreciated what he gave me that I never needed a piece of him like a check on his account that he didn’t even sign – just getting it was cool enough for me – or a sighting in New York or even an interview with the man. He’d given me more than enough. He was born on October 9, 1940. And given enough that it would have been so nice to see him live to the age of 75 and beyond that he so deserved to enjoy… even if, in a way, he obviously still lives in the enduring impact of his music.

Today, I love John Lennon more than ever. And thank he and Yoko for the 15 bucks.

This essay is adapted from an earlier version that ran on The Huffington Post on 12/8/10

Lennon’s solo releases—including many expanded editions—are available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI love John Lennon too.

All hail Lennon and Marx! FireSign Theater.

Absolutely a Beautiful RocknRoll American Story

I was 7 when I first heard “I Want To Hold Your Hand” and it was like nothing on the radio like it. Then came the British Invasion, and there were a lot of songs like it! But I was also a Johnist. He was the leader of the band, at least until 67. After that…but back then, if a band dissolved…but then the Moody Blues took a break in ’72 and came back in ’78, so it was possible. The only thing I mourn is what might have been…