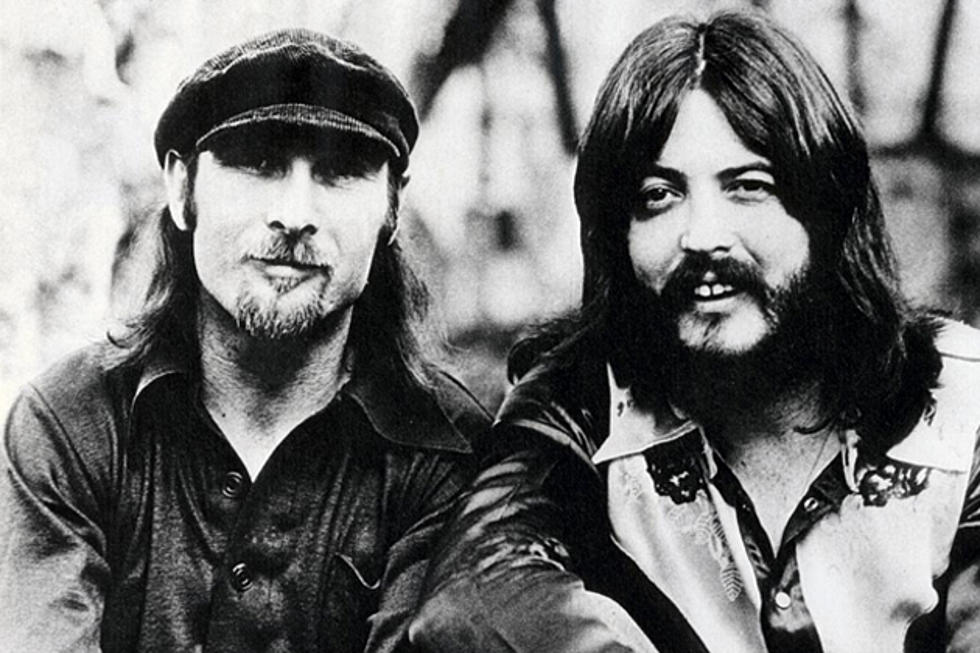

June 6, 2022: Jim Seals, of Soft-Rock Duo, Seals and Crofts, Dies

by Best Classic Bands StaffJim Seals, half of the soft-rock duo Seals and Crofts—whose 1970s hits included “Summer Breeze,” “Diamond Girl” and “Get Closer”— died on June 6, 2022. The news was confirmed on the Facebook page of John Ford Coley, who co-led another popular ’70s duo with “England” Dan Seals, the younger brother of Jim.

The cause of Jim Seals’ death was a “chronic ongoing illness,” according to the New York Times, which cited his wife as the source. Seals died at his home in Nashville. He was 80. The duo are the subject of a new boxed set. Gold & Rainbows: The Warner Bros. Years 1969-1978 is coming July 18, 2025, via the Lemon imprint of the U.K. label Cherry Red Records. The 5-CD collection is available for pre-order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Coley wrote, “Dan adored his older brother and it was because of Jimmy opening doors for us that we came to Los Angeles to record and meet the right people. This is a hard one on so many levels as this is a musical era passing for me. And it will never pass this way again as his song said. He belonged to a group that was one of a kind. I am very sad over this but I have some of the best memories of all of us together.”

James Eugene Seals was born in the small Central Texas town of Sidney, on October 17, 1941. He met Darrell George “Dash” Crofts in 1958 as members of Dean Beard and the Crew Cats, a rockabilly band led by the same-named singer/pianist dubbed the West Texas Wild Man. The same year that Seals and Crofts joined his band, Beard was asked to join the Champs, the Los Angeles group that was just coming off a national #1 instrumental smash, “Tequila.” The two friends headed west with Beard and also got the gig with the Champs, with Seals on tenor saxophone and Crofts playing drums. By 1959 Beard had departed the Champs but Seals and Crofts stayed with them, also adding vocal backups, billed as the Chimes. In addition, they began recording their own singles, at least one time billed as the Trophies.

By 1965, it had become obvious to the two friends that they were in a position to head out on their own and, besides, the Champs were fading quickly as the new British bands took over the rock scene. Seals had cut four singles for Challenge Records, and he opted to leave the group that year, although Crofts stayed on long enough for a Japanese tour. Upon his return, they both concentrated on session work and songwriting, lending their talents to the likes of Rick Nelson, Buck Owens and Gene Vincent. (Seals also reportedly contributed sax parts to More of the Monkees, the made-for-TV band’s second LP.)

Sometime in the early ’60s, Seals and Crofts also joined a band called the Dawnbreakers, and during that time they were introduced to the Baháʼí Faith, a century-old religion with roots in the Middle East. Baháʼí would become central not only to the lives of both artists but to their music: many of their songs were written around ideas espoused by Baháʼí scriptures, and Seals and Crofts, even at the height of their fame, never failed to talk about it and spread its principles every chance they got.

The most prolific and high-profile phase of the Texans’ career began in 1969, when the two musicians decided to team up as a duo that they would simply call Seals and Crofts. With Seals playing guitar, saxophone and violin, and Crofts on guitar and mandolin—both sharing vocals and harmonizing pristinely—they began crafting music that fit snugly into the still-emerging soft-rock and singer-songwriter modes.

It wasn’t easy at first. Their self-titled 1970 debut album failed to chart at all in the United States; the followup, Down Home, later that same year, squeaked in at #122. Even a gig at New York’s famed Fillmore East, opening for England’s Procol Harum in 1970, failed to ignite their career as a stand-alone act. The third album—and first for the Warner Bros. label, titled Year of Sunday—fared even worse than the one before it, peaking at #133 in early 1972.

They were determined though, and in 1972, Seals and Crofts finally caught their break. One of their self-penned tunes, “Summer Breeze,” was released at the perfect time, August 1972, and found its audience readily. The single climbed all the way to #6 in America, and boosted the album of the same name to #7 in Billboard’s LP chart. Nearly a decade and a half since they’d joined the Champs, Jim Seals and Dash Crofts were finally tasting success.

“Hummingbird,” the song that opened the Summer Breeze album, reached #20 in early 1973, but by that time the duo was already at work on their next album. It, too, took its name from a hit single: “Diamond Girl,” its authorship again credited to both Seals and Crofts, became their second top 10 hit, peaking at the same position as “Summer Breeze,” #6.

The Diamond Girl album jumped to #4, outpolling the earlier collection—it would become the biggest seller of their career, establishing Seals and Crofts permanently as fixtures on soft-rock radio. Another single from the album, “We May Never Pass This Way (Again),” climbed to #21 and fans waited to see what the pair—now one of the hottest acts in the business—would come up with next.

What they came up with was a single—and album of the same name—that looked to Seals and Crofts’ faith for its inspiration and ultimately caused a severe blow to their popularity. “Unborn Child,” a song co-written by Seals and Lana Bogan, the wife of the duo’s recording engineer Joseph Bogan, was unabashedly anti-abortion in its lyrical stance. Released in early 1974, just a year after the landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision that ruled in favor of a woman’s right to choose the procedure, “Unborn Child” alienated a sizable segment of Seals and Crofts’ audience. Warner Bros. begged the duo not to release it, but Seals and Crofts ignored the warnings. While most of the pair’s more dedicated fans were aware of Seals and Crofts’ adherence to the Baháʼí Faith, many thought they’d gone too far in bringing their religion so unambiguously into their music. The single stalled at #66, although there were enough other songs on the Unborn Child album to elevate it to #14.

They had undeniably taken a hit commercially—“King of Nothing,” the followup single, from the same album, topped out at #60, and as the middle of the ’70s came into focus, it remained to be seen just how Seals and Crofts would fit in. (Ironically, the year 1974 also saw Seals and Crofts playing perhaps their biggest-ever gig, but one of the strangest: California Jam, a festival date that put them in the company of Black Sabbath, the Eagles, Deep Purple and others wielding considerably more volume.)

I’ll Play for You, their 1975 album, brought them back into the game, peaking at #30, with the title track finding its way to #18. But if there was any doubt in anyone’s mind, by 1976 it had evaporated. The single “Get Closer,” once again taken from an album of the same name, brought Seals and Crofts right back to that now-familiar #6 position—their third and final visit to that same spot. The album itself reached #37, their last to go gold.

For the most part, that was it for Seals and Crofts’ chart reign. There would be one last top 20 single, 1978’s “You’re the Love,” and an album, Takin’ It Easy, in 1978, that reached #78 (it even contained a disco-flavored tune). The Longest Road, released in 1980, didn’t even chart, and Warner Bros. dropped the duo.

With the music scene having shifted radically away from the sound they favored, Seals and Crofts decided to break up the act that same year, although they did occasionally continued to meet up for Baháʼí-related events. Crofts continued to play music in a country vein, while Seals took up coffee farming in Costa Rica.

Seals and Crofts reunited in 1991 for about a year and then again in 2004. They recorded a final album that year, titled Traces, but the audience for their kind of music had long ago moved on.

Seals and Crofts’ recordings are available here.

Related: Musicians we lost in 2022

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversation“Summer Breeze” will always be present.

R.I.P. Jim –

Thank you for some great albums, and I still remember the great concert you and Dash Crofts performed at the Pittsburgh Civic Arena in March, 1974.

I saw them in 1973 in Miami. They were flying high at that time, it was sold out. I was blown away how great they were, and that band they had was tight as a drum. They blew the roof off. I saw Jim and his brother Dan in Asheville in 2006. Great show also.

If you’re lucky, every once in awhile you might sometimes hear a song that you’ve heard many times, but this particular time you hear it in a certain context, and a window opens in your mind as if you’re hearing this song for the first time. I recently had that experience hearing “Hummingbird ” on Sirius while driving one day. As it was, that song had strong warm memories for me from the early seventies. But on this day, as i was driving along on an open interstate, a window in my mind did indeed open, and I was somehow able to listen into this recording in a way that was as if I was hearing it for the first time. And what a musically harmonic odyssey it was, especially the end section, where their harmonies soared with seemingly neverending modulations. It was breathtaking, and i could hardly believe that I had never perceived it in such a way before. I can only say that, since then, I’ve never regarded their “folk ” musicality in the same way. Thank you, Jim, and RIP.

Jim Seals is likely smiling down from heaven, seeing that their song “Unborn Child” still stirs people’s emotions/thoughts to this day.

I am not going to preach, but a teenage lady friend of mine (plutonic), was going through a personally bad time in 1974, and her decision to go full-term was significantly influenced by that song.

Nearly fifty years later, Ali’s daughter is a vibrant, loving, and contributing members of society, and ironically, as an RN.

Will never understand the irony of how Seals and Crofts were shunned so drastically for simply being pro-life (especially when most of the lyrics were written by a woman; their recording engineer’s spouse, as reinforced in the article above), and yet, Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach”, ten years on, was celebrated (even when you agree with the song’s sentiments).