The death on November 19, 2017, of the notorious cult leader and career criminal Charles Manson at age 83 didn’t have many people mourning, particularly those who were young at the time and remember first-hand hearing of the brutal, senseless murders he orchestrated in Los Angeles in 1969. To the baby boom generation, Manson represented the beginning of the end of the idyllic hippie dream: He may have looked like all of the other longhaired acidheads and free-lovers roaming the city streets and escaping to rural communes but, as was quickly established, he wasn’t like them.

The death on November 19, 2017, of the notorious cult leader and career criminal Charles Manson at age 83 didn’t have many people mourning, particularly those who were young at the time and remember first-hand hearing of the brutal, senseless murders he orchestrated in Los Angeles in 1969. To the baby boom generation, Manson represented the beginning of the end of the idyllic hippie dream: He may have looked like all of the other longhaired acidheads and free-lovers roaming the city streets and escaping to rural communes but, as was quickly established, he wasn’t like them.

Not at all.

Except for one thing: Like millions of others in the ’60s, Charlie Manson wanted to be a rock star. And the fact that he did not become one, that he was in fact rejected by real movers and shakers of the music business, may very well have triggered his crime spree.

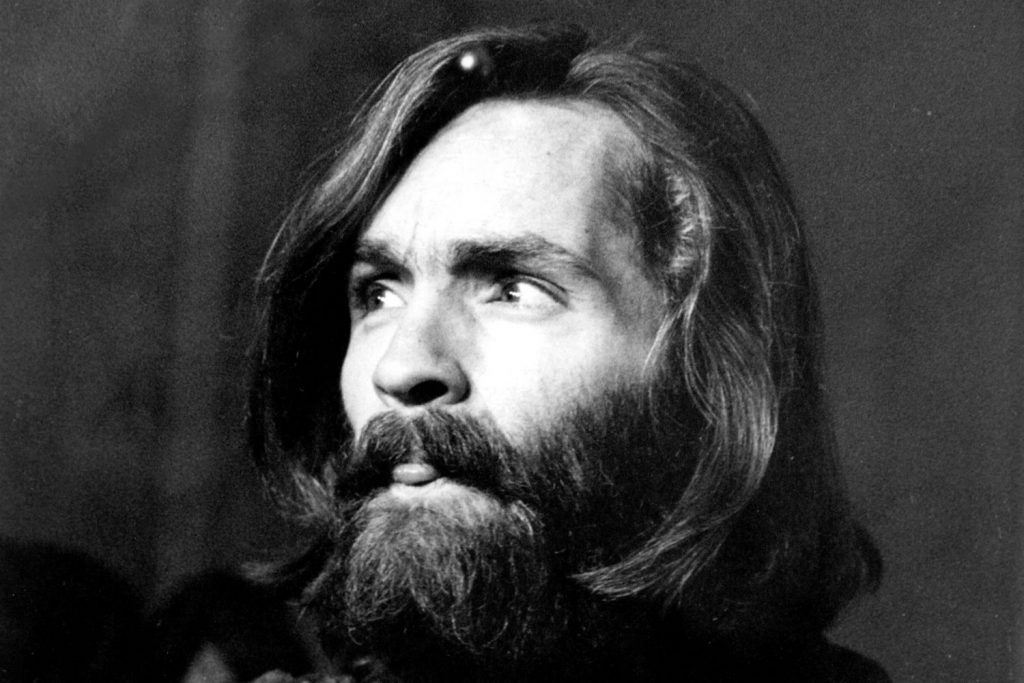

The backstory has been told countless times, in books and magazine articles, in films and television specials and everywhere else stories like this are told. The name Charles Manson—and of course, the images: the steel-eyed demonic stare, the swastika carved into his forehead—has caused shudders of fear since he and his deluded, deranged “family” first came to public attention. Even today, after his demise, some are posting on social media sites that they can finally sleep at night, that now they can sigh with relief, as if the frail octogenarian who’d been incarcerated for more than four decades was somehow going to escape and find his way into their bedroom or, worse yet, find an unquestioning, brainless disciple to sneak into their homes and do them in, scrawling foreboding screeds on the wall in blood.

But what’s really bizarre is that there are others who find legitimate sadness in his passing. Manson, shockingly, has always had bona fide admirers, loners and losers who, for reasons known only to themselves, find his story attractive. They see him as a victim of the system who gave it to “the man” and shook polite and satisfied society to the core with his proclamations of impending revolution and race war. That Manson learned in prison how to manipulate others, get them to do his bidding—even to murder—is lost on them. Or maybe it isn’t; maybe that’s the part they like, that this evil outcast was able to so easily cast a spell over young, gullible, searching souls, to cajole them into believing he was a messiah, a prophet whose every word was gold, whose commands were to be obeyed, blindly, laws and basic morals be damned.

To some, even nearly a half-century after the Tate-LaBianca murders, Charles Manson was a t-shirt-worthy rock star—even though he never made the charts.

He wanted to be one, that much is known. Manson was savvy enough to grasp that the budding counterculture of the late ’60s, with rock music as its guiding light, was the ticket that could bring him the dominance he so craved. In the early ’60s, while imprisoned in Washington State (not for the first time), he’d learned how to play guitar by one Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, a former member of the Ma Barker gang.

In his autobiography Karpis wrote, “This kid approaches me to request music lessons. He wants to learn guitar and become a music star. ‘Little Charlie’ is so lazy and shiftless, I doubt if he’ll put in the time required to learn. The youngster has been in institutions all of his life—first orphanages, then reformatories, and finally federal prison. His mother, a prostitute, was never around to look after him. I decide it’s time someone did something for him, and to my surprise, he learns quickly. He has a pleasant voice and a pleasing personality, although he’s unusually meek and mild for a convict. He never has a harsh word to say and is never involved in even an argument.”

By 1967, now out of prison and living in San Francisco—at the peak of the Summer of Love—Manson went to work, attracting a following, especially among young women, some of them underage, all of them lured by his supposedly magnetic personality and twisted philosophy and theology. The gist of it was this: If they stuck by him, trusted him, did whatever he asked, not only would their own lives be blissful but they’d be ground-floor witnesses to the birth of the better world that he was going to create. Toss in some satanic stuff, a few ideas borrowed from Scientology, a bunch of boilerplate be-here-now hippie idealism and the skills of a back-country preacher and the legend of Manson was on its way.

There was, of course, sex and drugs and—this being California in the late ’60s—rock ’n’ roll. Manson, into his 30s by that time, and more a fan of Bing Crosby than the Beatles, enjoyed nothing more than surrounding himself with his nubile, willing minions and a handful of male acolytes and singing them the songs he’d written, accompanying himself on his guitar. Oh, Charlie, they would tell him, you’re the very best, you’re going to be bigger than the Beatles! He had no doubt that it was to be.

(As an aside, it has long been rumored that Manson tried out for a role in the TV sitcom The Monkees. Fake news, that. He was still in jail in 1965 when the auditions took place, and remained locked up until 1967.)

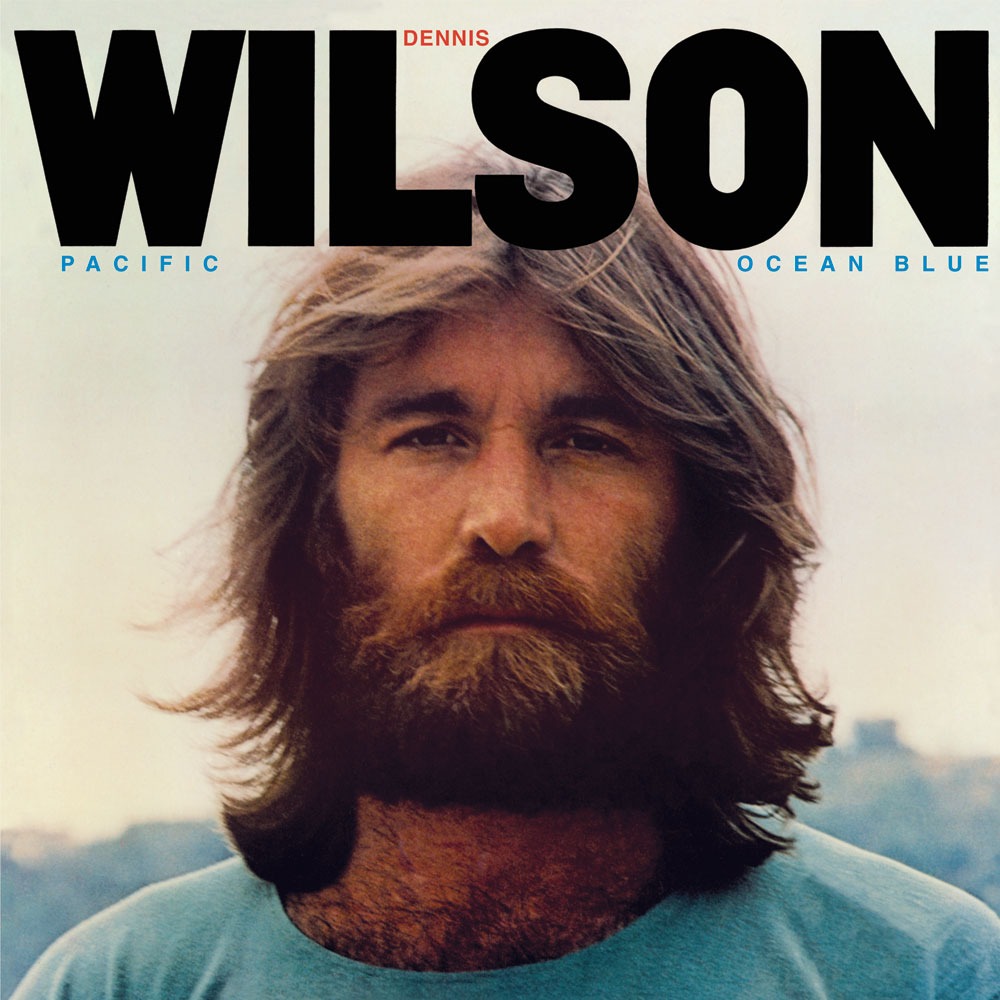

Toward the end of the decade, Manson—who’d set up camp at the remote 500-acre Spahn Ranch outside of L.A.—had already morphed into the messianic figure of legend, and his fans were eager to spread the word. That’s where it was at the day that Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson picked up a couple of girls hitchhiking. You should meet our guru, they told the rock star, who had driven them to his home for a bit of partying. Yeah, he sounds like an interesting cat, Wilson had to admit. Hours later, Charlie Manson arrived, bringing with him a dozen or so of his closest girlfriends.

They didn’t leave; in fact, their numbers grew, all sorts of human detritus taking over Wilson’s pad. The women serviced the drummer, who enjoyed making music with their leader. Dennis Wilson, like the others, became enthralled with the charismatic singer-songwriter who so easily got anyone to do whatever he asked. The Beach Boy introduced Manson to his brothers, Brian and Carl, who got as far as planning to record Dennis’ new friend, and to his other music-biz pals, among them Terry Melcher, the son of actress-singer Doris Day. Melcher had produced hits for the Byrds and many others and agreed to listen to Manson’s songs.

He was not impressed. He thought the songs kind of sucked and the singer creeped him out. Then, upon witnessing Manson turn violent during an altercation at Spahn Ranch, Melcher not only declined to sign Manson but severed ties, as did Wilson.

It wasn’t long after that that the first of the notorious Manson murders took place. The brainwashed killers entered the house that the eight-months-pregnant actress Sharon Tate had been renting with her husband, director Roman Polanski, killing her and four others.

That house had, until recently, been occupied by…Terry Melcher. Manson family member Tex Watson later affirmed that it was, indeed, Melcher the gang had been hoping to kill, on orders given by Manson. They had not known that he’d moved out but figured we’re here, might as well kill someone.

There was much more to the story though—the real crazy stuff was what went on under the hood. As is well known—revealed among the grisly post-murder facts—Manson had for some time been telling anyone who would listen about Helter Skelter, the term he gave to what he believed was an impending all-out race war soon to blanket the land. He’d heard the words in the Beatles’ “White Album” song of the same name, written by Lennon and McCartney. The lyrics, Manson said, tapped into what he had been saying, that the black people, tired of being exploited, were going to rise up and annihilate the white race. In fact, he proclaimed, all of the songs on the “White Album” supported his ideas: The Beatles too were awaiting the arrival of Helter Skelter! And they were telling him, Charlie Manson, to do his part to ignite it.

So sure was Manson that this race war was about to happen that, when he gave orders to carry out the Tate murders, he used his command as a catalyst, telling his family that it was time for Helter Skelter, that they were going to make it all happen. The next night, when the family murdered the elderly couple Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, who had no connection to the Tate party or the entertainment industry, one of them scrawled the misspelled “Healter Skelter” on the couple’s refrigerator, in blood. Also in blood: the phrase “political piggy,” likely a reference to George Harrison’s “White Album” song “Piggies,” one that Manson particularly liked.

The arrest and imprisonment of Manson and the family members responsible for the killings put the kibosh on any dreams the crazed cult leader had of becoming a rock star.

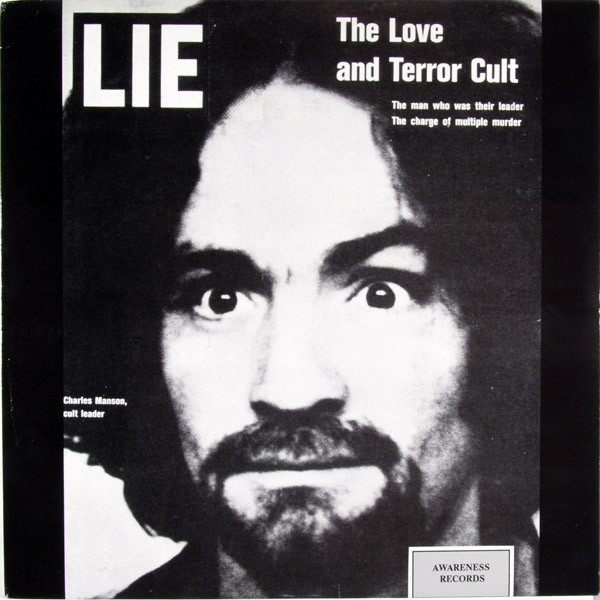

But hey, Manson did get an album out! And some folks not only bought it but said it was pretty good. It even received some positive reviews in the underground music press. He didn’t release it himself though—he was a bit preoccupied, what with his trial and imprisonment and all. Titled Lie: The Love and Terror Cult, its front jacket based on a nearly identical Life magazine cover, the half-hour recording, made in 1968 at L.A.’s famous Gold Star Studios, and released in 1970, consisted of some 14 Manson original compositions, all featuring his voice and guitar.

Listen to Manson sing “Look at Your Game, Girl”

And here’s another from Lie, “Garbage Dump”

With Manson’s instant infamy, no reputable record company would release Lie, so a producer/manager named Phil Kaufman, allegedly responding to the direct post-arrest pleadings of Manson, took it upon himself to get the music out there, initially on the independent Awareness label. Some 2,000 copies of the LP were pressed and it was distributed by Trademark of Quality, the then-leader of the bootleg album market.

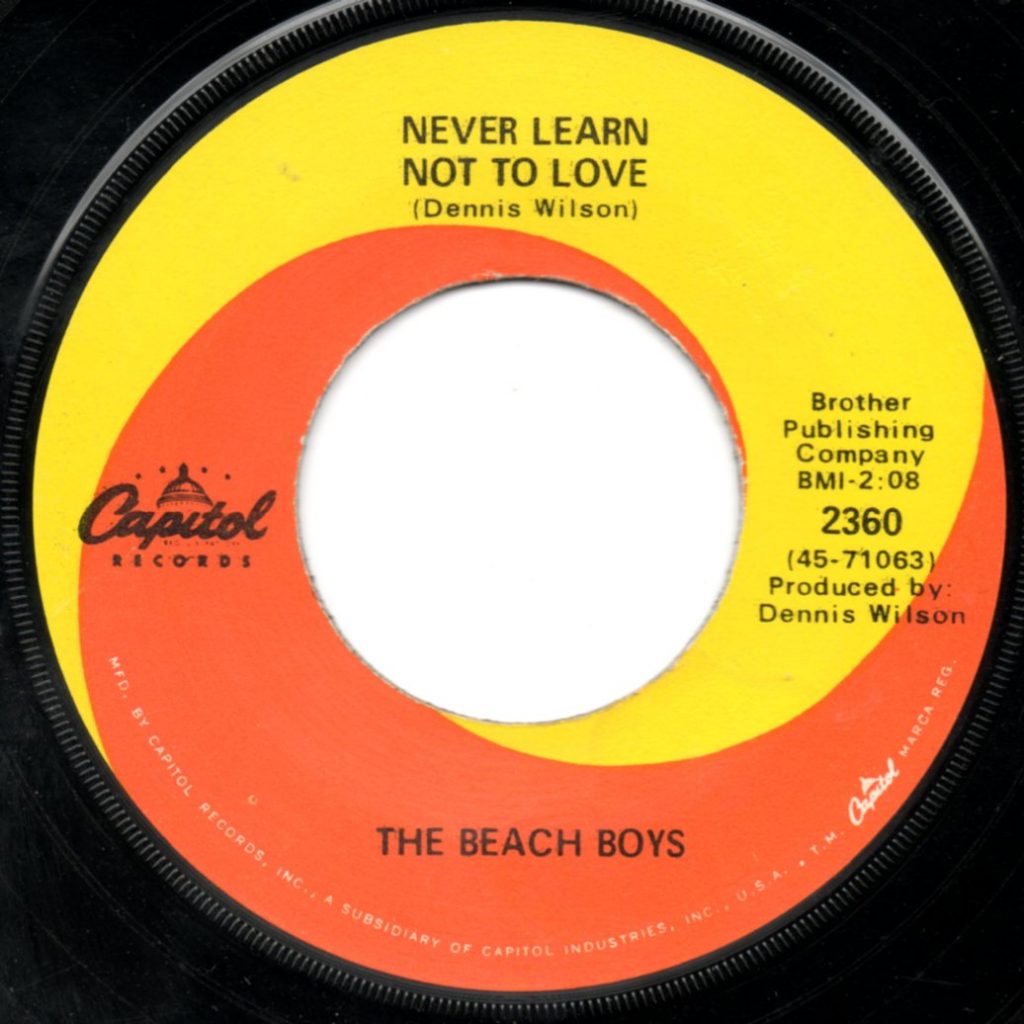

The songs on Lie? By most accounts, not worth the vinyl they were pressed on. But some disagreed. One track, titled “Cease to Exist,” was co-written with Dennis Wilson, and even recorded by the Beach Boys under the title “Never Learn Not to Love.” The song—with the title phrase changed to “cease to resist”—appeared both on the band’s 1969 20/20 album and as the B-side of the single “Bluebirds Over the Mountain.” (It was credited only to Dennis Wilson on both.) “Cease to Exist,” in its original form, was also later covered by the Lemonheads, Rob Zombie and Redd Kross, among others.

Watch Dennis Wilson fronting the Beach Boys for a live version of “Never Learn Not to Love,” the song he co-wrote with Manson

Another Lie song, “Sick City,” was covered by Marilyn Manson, who was not related to but took his surname from the notorious killer. And “Look at Your Game, Girl,” one of the first songs Manson recorded, in September 1967, appears as a hidden track on Guns N’ Roses’ 1993 album The Spaghetti Incident?, while artists as diverse as Devendra Banhart and G.G. Allin have also included Manson material in their shows and recordings. Lie was later reissued by the legendary ESP-Disk label and several others, in both the U.S. and the U.K.

As of now, Wikipedia lists nearly 20 other albums and several singles as part of its Charles Manson discography, plus a few attributed to the Manson family.

Charles Manson never did become a rock star, not in the literal sense. But he did find a way to get his music heard and, in his own way, made a small dent on rock history. Thankfully, it’s not a route that other wannabes have chosen to follow.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationThe Charles Manson connection to The Beatles and their “White Album” has always bothered me. I actually know people who believe it was Manson who influenced the Beatles writing, when, in fact, Manson got the phrases from the already released album. It’s such a shame that whether temporarily, or permanently, people seem to connect the genius of that album to Manson. I always liked Bono’s introduction to U2’s live version of “Helter Skelter”, from their “Rattle and Hum” album, “Charles Manson stole this song from The Beatles, We’re stealing it back!”, as they launch into “Helter Skelter”. Let’s hope it has since been put under lock and key.