The Byrds’ ‘Sweetheart of the Rodeo’: Cornerstone of Country-Rock

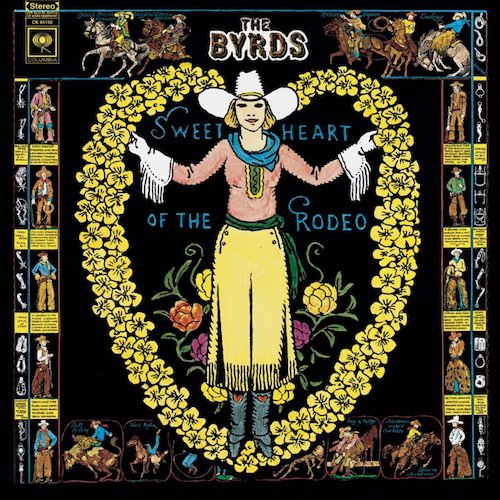

by Sam Sutherland Well over fifty years after its creation, Sweetheart of the Rodeo looms as a cornerstone of country-rock and point source for alt-country and Americana, The Byrds’ most consequential stylistic stroke since the band’s pioneering folk-rock debut three years earlier. Yet when planning for the album began during the first months of 1968, the group was struggling against commercial headwinds and crippled by personnel changes, reduced to co-founder and lead guitarist Roger McGuinn and bassist Chris Hillman.

Well over fifty years after its creation, Sweetheart of the Rodeo looms as a cornerstone of country-rock and point source for alt-country and Americana, The Byrds’ most consequential stylistic stroke since the band’s pioneering folk-rock debut three years earlier. Yet when planning for the album began during the first months of 1968, the group was struggling against commercial headwinds and crippled by personnel changes, reduced to co-founder and lead guitarist Roger McGuinn and bassist Chris Hillman.

The duo was licking its wounds at the disappointing reception to the band’s fifth and most ambitious album, The Notorious Byrd Brothers, which found them stretching to meet the high bar set by Sgt. Pepper. With its aggressive electronic edge and topical material reflecting political and cultural unrest, Notorious had earned them some of the best reviews of their career. By the time of its completion, however, internal dysfunction had boiled over, with McGuinn and Hillman firing David Crosby and drummer Michael Clarke. That album’s lead-in single, a wistful version of Gerry Goffin and Carole King’s “Goin’ Back,” had stalled after its October ’67 release, with the album likewise peaking at #47 on the Billboard album chart after its release in early January.

By February, the two surviving members had drafted Hillman’s cousin, Kevin Kelley, as drummer and embarked on a trio tour that exposed their lack of firepower. With McGuinn and Hillman as the only signatories to a new Columbia Records contract, the plan was to proceed with hired sidemen. McGuinn, meanwhile, envisioned an even more ambitious full-length that would double down on Notorious’ scale by attempting a pan-generic survey of 20th century music.

Related: When “Mr. Tambourine Man” hit #1

The Byrds in a 1968 publicity photo. Left to right: Kevin Kelley, Gram Parsons, Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman

Enter Gram Parsons. The Florida-born, Georgia-raised Parsons was a new kid in town seeking success with the International Submarine Band, whose debut album was weeks from release. Invited by Hillman to audition for the Byrds on piano, Parsons’ voice, guitar and original songs quickly established him as more versatile—and ambitious. Not content to be a mere hired hand, the charismatic Parsons lobbied for a shift away from McGuinn’s grand concept. Instead, Parsons pushed for a narrower focus highlighting the country elements he was already exploring with the ISB.

Not that the Byrds were strangers to country, especially Chris Hillman. As a teenager, he’d established himself as a mandolin player with Southern California bluegrass bands. As a Byrd, he had persuaded his bandmates to cover Porter Wagoner’s 1955 hit, “A Satisfied Mind,” and his Byrds debut as lead singer and songwriter came with “Time Between,” a brisk country shuffle on 1967’s Younger Than Yesterday. In Hillman, Parsons gained a crucial ally and future collaborator, and together they closed ranks with McGuinn around Sweetheart’s focal concept. With producer Gary Usher, they headed for Nashville and a week of March sessions reinforced by seasoned country session musicians. Subsequent Los Angeles sessions would follow in April and May.

Listen to “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” from Sweetheart of the Rodeo

Sweetheart’s opening track underlined the Byrds’ pivot from Hollywood to Music Row vividly. “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” found them turning yet again to Bob Dylan for material, this time tapping into the bucolic spirit of the as-yet-unreleased Basement Tapes. In place of McGuinn’s signature Rickenbacker 12-string, the arrangement spotlighted Lloyd Green’s giddy pedal steel filigree, dancing between the vocals above a loping country beat. The album would close with another Basement Tapes gem, “Nothing Was Delivered,” but the set list otherwise leaned on country and folk material, plus a recent R&B ballad, William Bell’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water.”

Listen to “You Don’t Miss Your Water”

Related: 50 years later, McGuinn and Hillman performed the album on tour – Review

Bell’s soulful weeper was tied to Parsons’ no-longer-hidden agenda in his Sweetheart input, a second draft for what he deemed “cosmic American music”—a junction of Southern idioms that prized both white country and black rhythm ’n’ blues. Vocal harmonies, pedal steel (by Jay Dee Maness) and honky-tonk piano (by Earl P. Ball) were anchored in Nashville, while Bell’s lyrics were pure Memphis, but Parsons’ original vocal ran afoul of protest from Lee Hazlewood and LHI Records, to which the International Submarine Band was signed. McGuinn tracked a new vocal lead in a compromise intended to quell the dispute.

Listen to the Gram Parsons-sung version of “The Christian Life”

Now listen to the official, Roger McGuinn-sung version

The same fate befell several other Sweetheart tracks, most notably “The Christian Life,” an Ira and Charlie Louvin classic celebrating faith despite the loss of less devout friends. Parsons may have been a wealthy trust-fund kid and practicing libertine, but his reverent vocal featured here honored the Louvins’ sincerity, nodding toward the axis of sin and soul shared by country and R&B. As heard on the finished album, McGuinn’s sarcastic drawl betrays his ambivalence, if not contempt, for the Louvins’ fervor.

The legal détente with Hazlewood and LHI over Parsons’ ISB obligations didn’t entirely erase him from the tracks. Most crucially, Parsons landed two original songs on the album. “Hickory Wind,” written with former ISB member Bob Buchanan, was a homesick reverie, a country waltz set against sighing fiddles and graced with gorgeous vocal harmonies. Parsons’ aching lead vocal projected weary vulnerability, alluding to worldly “riches and pleasures” that prove powerless against loneliness.

Listen to “Hickory Wind”

Parsons was less fortunate, however, with his second Sweetheart original, “One Hundred Years From Now,” another concession to LHI. Once more, McGuinn was pressed into service for the lead vocal, providing one of the set’s two mid-tempo rockers alongside “Nothing Was Delivered.”

Listen to “One Hundred Years From Now”

Parsons’ lead vocals were retained for covers of Merle Haggard’s penitent “Life in Prison” and Luke McDaniels’ barroom lament, “You’re Still on My Mind,” clinching the newest Byrd’s prominence on Sweetheart.

Elsewhere on the album, McGuinn turned to Woody Guthrie for “Pretty Boy Floyd,” which cast the ’30s gangster as a Depression-era Robin Hood. Hillman, meanwhile, contributed the album’s other nod to country gospel, “I Am a Pilgrim,” and took the lead vocal on Cindy Walker’s “Blue Canadian Rockies.”

Listen to “I Am a Pilgrim”

By the time Sweetheart of the Rodeo was released on August 30, 1968, Parsons had left the group after refusing to play dates in South Africa. Hillman would soon follow him to join forces in the Flying Burrito Brothers, building on the “cosmic American” blueprint that would be further refined with Parsons’ solo albums with protégé Emmylou Harris.

Although other bands, including the Beatles, Lovin’ Spoonful, Buffalo Springfield and Monkees had nodded affectionately toward country, the Byrds had leaned into country too far, too soon, for Sweetheart, notching the lowest sales of any Byrds album to date: the album peaked at #77 in Billboard. Over the next year, however, the project’s legacy would slowly reveal itself in a rising tide of country-rock full-lengths from the Burritos, Poco, ex-Byrd Gene Clark and, yes, the Byrds themselves, in a lineup now featuring Clarence White, whose nimble country guitar leads had been featured on the band’s studio albums since 1967. [The recording, and other Byrds favorites, are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.]

Related: Our review of 2018’s “Sweetheart” anniversary tour

Bonus video: Watch the Byrds perform “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” and “This Wheel’s on Fire” on Playboy After Dark in 1968

10 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI’m sure Hazlewood was upset with Gram Parsons’ participation in the Byrds and this album — because the record companies seemed hell bent on getting in the way of good music back then if it crossed their precious contractual lines — but I think his objections were used by McGuinn to get a more balanced album that was leaning too heavily toward Parsons’ influence. If you read some of Gram Parsons’ comments about the situation I think he felt the same way. I agree that McGuinn should have left “The Christian Life” alone and picked “You’re Still On My Mind” instead to re-vocal, a song he wound up singing on stage anyway.

A truly great album that I hated when it came out. Same with Nashville Skyline and John Wesley Harding. I sure had bad taste back then.

With appreciation for “Sweetheart” aside, I can’t fathom the “poor reception” the Byrds received for “Notorious” — one of the greatest LPs to come out that era, and a landmark of its own. As much as I absolutely loved the “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” anniversary tour Hillman and McGuinn did with Marty Stuart and the Fabulous Superlatives, if truth be told, the best parts of the show was when they played much of “Notorious.” That really slayed me, But, honestly, when the band opened the show playing “Positively 4th Street,” and Hillman and McGuinn entered the stage from opposite ends (McGuinn picking his twelves string) it was all over but the crying — literally. They could have played anything after that and it would have been fabulous. Still, I would have like to have heard the record that McGuinn had envisioned after “Notorious,” though without David Crosby, a key element to the stylings of the Byrds songs lineup would have been lacking in an essential key ethereal aspect of what was so compelling in the complexity of their records.

I thought they opened all of those shows with “My Back Pages.” In any case, it was a great show.

You’re right, Jeff. “My Back Pages” it was. I got my twang mixed up.

Anyone who saw the 50th anniversary tour of this album and bought the legacy version knows how great the music was and still is—Marty Stuart provided expert backup and reverence for the songs.

You’re so right, Jon. The played those songs like they loved them as much as we all did. I sure wish they would do that again, and in my dream world, WITH David Crosby involved.

Also check out John Stewart’s ground-breaking 1969 album “California Bloodlines” which was one of the first records to successfully blend folk, rock and country creating the Americana hybrid.

Roger rocks his Rickenbacker. Thanks George, Bob, Ravi, et al.

Saw the reformed Byrds live at a nice venue paired with Marty Stuart’s Champions of the Rodeo band. Dual artists blew the house away. In the same week Mavis Staples wowed with a superb vocal rendition which will never be repeated in the venue due to some old farts.

I was lucky enough to see both shows just mentioned. What a great week likely never to be heard again.

Folks came from far away from the hills of SW Va to hear some great musicians.