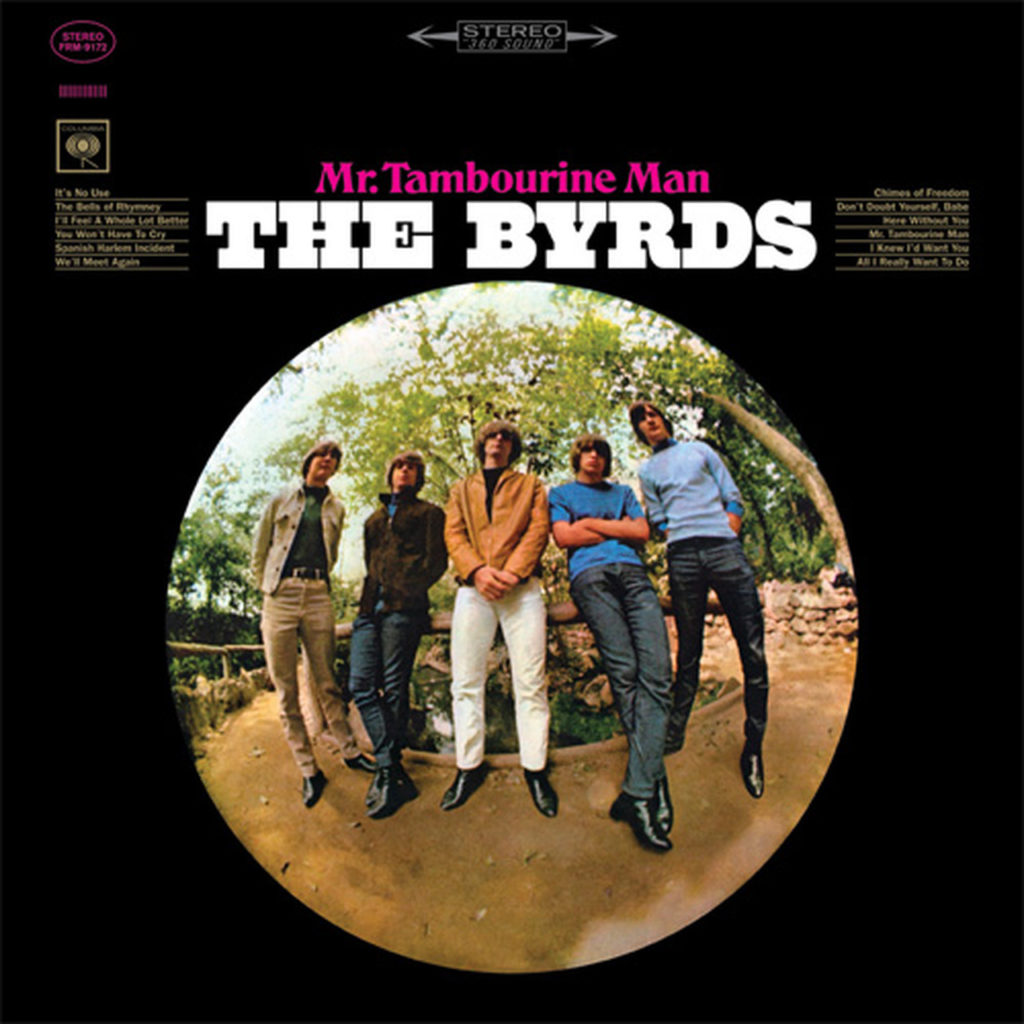

More than five decades on, The Byrds stand as folk-rock exemplars who drew a bright line between the Beatles and Bob Dylan, forging an elegant style that fused the exhilarating bloom of the British Invasion with Dylan’s poetic and topical gravitas. By June 1965, when the Los Angeles quintet released its debut album, Mr. Tambourine Man, the title single had heralded that synthesis in the “jingle jangle morning” of its vividly retooled Dylan song, providing a near-perfect entry point to an album giving equal weight to literate electric cover versions of contemporary folk songs and the band’s impressive original material.

More than five decades on, The Byrds stand as folk-rock exemplars who drew a bright line between the Beatles and Bob Dylan, forging an elegant style that fused the exhilarating bloom of the British Invasion with Dylan’s poetic and topical gravitas. By June 1965, when the Los Angeles quintet released its debut album, Mr. Tambourine Man, the title single had heralded that synthesis in the “jingle jangle morning” of its vividly retooled Dylan song, providing a near-perfect entry point to an album giving equal weight to literate electric cover versions of contemporary folk songs and the band’s impressive original material.

Mr. Tambourine Man can also be heard as the second work in a trinity of definitive albums that codified the genre, preceded in March by Dylan’s electric/acoustic hybrid, Bringing It All Back Home, and followed that summer by the quantum leap of “Like a Rolling Stone” and its full-length manifesto, Highway 61 Revisited. Their combined influence could be heard in a widening circle of new rock bands and newly electrified folk artists from that point forward.

Listen to the Byrds’ #1 hit single of “Mr. Tambourine Man”

Future Byrds Roger (né Jim) McGuinn, Gene Clark and David Crosby had bonded in early 1964 over a shared infatuation with the Beatles that inspired them to quit gigs with established “collegiate” folk acts. All three had headed for Los Angeles, where McGuinn’s acoustic reworkings of Beatles songs caught Clark’s ear, leading to their partnership as a duo. When Crosby heard them singing together at the Troubadour, he added his velvety high tenor, opening their vocal blend to more complex harmonies. He also brought a valuable ally in manager Jim Dickson, who took them on as clients.

Related: Our Album Rewind of the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo

Dickson, an influential folk and bluegrass producer, helped the trio, now billing itself as the Jet Set, get studio time at World Pacific Studios, where they began building a repertoire of original songs inspired by what they heard emanating from Liverpool and London. The summer release of A Hard Day’s Night heightened that ambition, influencing not only their sound but their look, starting with the electric guitars they saw George Harrison and John Lennon playing on screen. McGuinn bought a Rickenbacker 12-string, drawing from his prowess as a guitarist and banjo player as he built a personal style on the instrument.

When Dickson brought them an acetate of an unreleased Bob Dylan song, the band was initially unimpressed, but with a newly recruited drummer, Michael Clarke, they began rearranging “Mr. Tambourine Man”’s brisk 2/4 pace and caffeinated, word-drunk lyrics, slowed to a stately 4/4 tempo. McGuinn crafted an eight-bar, 12-string intro around a repeated 14-note figure closer to Bach than Chuck Berry, and together they pruned Dylan’s sprawling lyrics, discarding three of its four verses, leaving only the evocative second verse and the yearning chorus. Invited to hear their handiwork, Dylan was delighted by its energy and unfazed by their ruthless edit. “Wow,” he enthused, “you can dance to that!”

By Thanksgiving 1964, the band had a bass player, Chris Hillman, a recording contract with Columbia Records, and a new name, the Byrds, retaining McGuinn’s preoccupation with flight and adding a misspelled wink to their heroes. The Dylan song that had been an outlier was now the candidate for their first single.

The Byrds at a recording session in Los Angeles, California, January 28, 1965. From left: Jim McGuinn (later referred to as Roger McGuinn), Chris Hillman, Gene Clark, David Crosby and Michael Clarke on drums. (Photo by CBS via Getty Images, via BMG Books)

On Jan. 20, 1965, producer Terry Melcher booked a session to record the song but decided the full band needed more time to cohere, tagging members of L.A.’s first-call “Wrecking Crew” as rhythm section. Hal Blaine (drums), Larry Knechtel (bass), Jerry Cole (guitar) and Leon Russell (electric piano) backed the core trio of McGuinn, Clark and Crosby on vocals, while McGuinn’s indelible Rickenbacker lead was burnished by its run through an outboard compressor, a touch the session engineer added to tame feedback while adding sustain. The group’s airy vocal harmonies and McGuinn’s stylized guitar work established the band’s essential character despite the studio hands.

Neither love song nor dance craze, “Mr. Tambourine Man” was something else altogether. Between its circular guitar figure and McGuinn’s reedy lead vocal, the song evoked a waking dream, pleading with its shamanic title figure to “take me for a trip upon your magic swirling ship,” and to “cast your dancing spell my way—I promise to go under it.” That spell would help the record reach #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 five days after the album’s June 21 release.

Bob Dylan, on stage with the Byrds, at Ciro’s in West Hollywood, March 26, 1965 (Photo © Henry Diltz; used with permission)

The January session nursed a myth that the Byrds didn’t play on their debut, but only that day’s two songs (with Clark’s “I Knew I’d Want You” destined as B-side) relied on studio ringers. When album sessions resumed in March, the band was now self-contained. They were also consciously embracing the folk component, no doubt emboldened by label mate Dylan’s public support, cutting three more Dylan song and a fifth song from folk patriarch Pete Seeger.

Dylan’s playfully romantic “All I Really Want to Do” would be released as the album’s second single, only to be ambushed by Cher’s faithful cover, along with “Spanish Harlem Incident,” nearly as charming but just as slight. The fourth Dylan cover, however, plumbed the social consciousness of Dylan’s earlier protest songs, and would become one of the set’s finest deep cuts.

“Chimes of Freedom” was an anthem for an unspecified rebellion set “far between sundown’s finish and midnight’s broken tolls,” saluting warriors, refugees, rebels, outcasts, haunted lovers and underdog soldiers—a hazy confederacy that spoke to teenage rebels everywhere. It also helped move the Byrds, and with them rock, beyond the romantic tropes otherwise dominating the radio.

Seeger’s “The Bells of Rhymney” shared that track’s mid-tempo pace and sweeping sonic landscape, using lyrics from Welsh poet Idris Davies inspired by a Welsh mining disaster and a failed labor strike. That the Byrds’ version of a mournful broadside would become its best-known version adds further weight to the band’s accomplishment here.

Watch the Byrds perform “Bells of Rhymney” live in the concert film The Big TNT Show

The album’s Dylan and Seeger tracks reinforced its folk influence without overshadowing their Beatle-browed originals, with Gene Clark standing out as songwriter and the group’s strongest vocal soloist. As leader, McGuinn had chosen to claim the band’s folk features as his turf for solo vocals, yet it was Clark who was the charismatic front man during his tenure in the band.

Clark’s “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,” the album’s strongest rocker, is a classic kiss-off to an unfaithful lover, propelled by a sharp guitar hook with both L.A. and Liverpool precedents: The riff was first heard in “Needles and Pins,” a 1963 Jackie DeShannon single written by Jack Nitzsche and Sonny Bono (and echoed in DeShannon’s answer record, “When You Walk in the Room”) that became a hit the following years for the Searchers, who rendered it on an electric 12-string guitar. DeShannon herself is represented on the Byrds’ set with “Don’t Doubt Yourself Babe,” a winning slice of folk-rock with a Bo Diddley clave beat.

“Here Without You” offers further proof of Clark’s skill with moody ballads, a hushed confession of romantic longing offering typically lovely vocal harmonies with shifting inner part, while McGuinn and Clark show harmonic savvy on their collaborations, especially “You Won’t Have To Cry,” arguably the closest they came to channeling Lennon and McCartney.

With worthwhile covers, solid originals and no filler, Mr. Tambourine Man sustained a level of quality that invited favorable comparison with their heroes, the Beatles, who declared themselves Byrds fans and responded later that year with the folk-rock grace notes heard on Rubber Soul. The Byrds’ founding lineup would survive barely two years, with Clark’s departure tipping the band’s direction further in McGuinn’s favor, with the band branching out into psychedelia, Coltrane-inspired “raga rock” on “Eight Miles High,” and country-rock. But its formative folk-rock attack would endure to influence successive generations of musicians from Big Star to Tom Petty to R.E.M.

The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Watch the Byrds perform “Chimes of Freedom on Shindig!

9 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe title may be “I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better” but in the lyric he sings “probably.” Reflecting human ambiguity and indecision is what made Gene Clark a genius, especially for those who felt they were among (to borrow from Dylan) “the countless, confused, accused, misused strung out ones at worst.” Clark deserves to be heard by more listeners.

The first CD box set I ever bought was “The Byrds”. Worth every penny. You can get it cheaper now than I did 30 years ago.

It’s ironic that the Byrds were such fans of the Beatles (but then, who aren’t?), in that other than an impossible Beatles reunion, the reunion I’d most like to see would be the Byrds. And while with both Clark and Clarke gone, a full reunion is also not possible, and the three remaining Byrds really getting up there in years, with Crosby retiring from touring, a limited number of performances, that could be recorded, could still feasibly be possible if McGuinn and Hillman had any willingness to work with Crosby again, which, to our great misfortune, they do not, even though Crosby has expressed his willingness to engage in a reunion, and has promised to “behave,” it’s been no dice from the other two. Nearing the end of all of their lives, it’s a shame they can’t get beyond their age-old differences for the legacy of the music. However, if you’ve ever been in a band with toxic personalities, it’s easier to understand their reluctance to go there again. Still a terrible shame though.

Now that Crosby is gone as well, that makes a reunion (with only 2 members) even more unlikely.

There were attempts at reunions of the original Byrds, including one in 1972 that resulted in an album, but it didn’t do well or go very far. There was also “McGuinn, Clark and Hillman” in 1977.

No mention of short timer Gram Parsons

In what context? Parsons was not in the early lineups of the Byrds.

McGuinn and Hillman teamed for the Sweetheart of the Rodeo tour with Marty Stuart in 2018. Obviously not a full reunion but the album that came out last year is worth seeking out.

The Byrds were too cool and they could play and sing. Love all their music from the early 60s to the latter part of the decade. Love them!

I have written before re going 2 my cousin’s home in Mpls for Sunday dinners and would shoot pool w/ them in basement beforehand, listening over the year’s of 1st 2 Byrds’ records, being in heaven, socially and musically! Like 122inshade, Byrds box set was 1st box set I ever purchased..Byrds music were soundtrack of 60’s 4 me & so many others…deeply spiritual, folky, rocking, harmonious, and still are today, all these years later…a band I still care about deeply, love & admire, clearly, imo, coming 2gether for the times and music…and the history..a seminal band 4 me, listen way more than the Beatles…