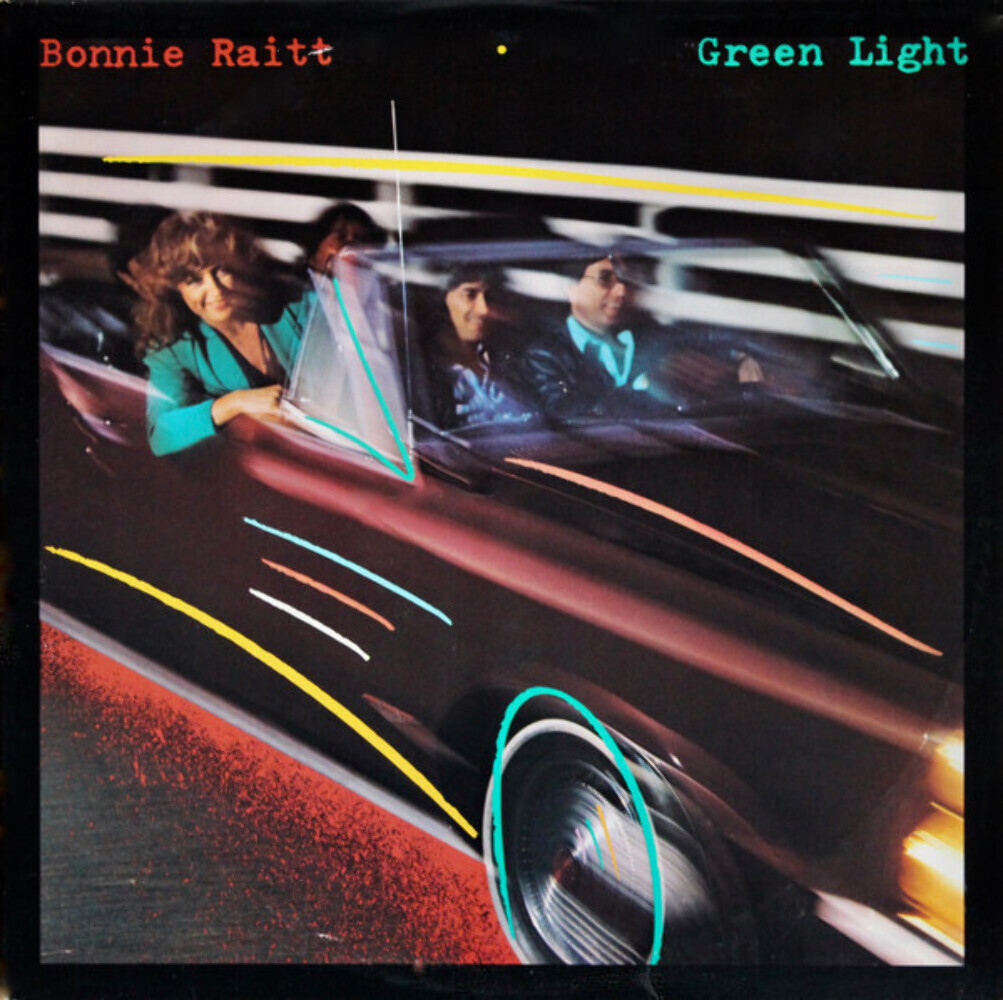

Bonnie Raitt Gives It One More Try with ‘Green Light’: Review

by Mark Leviton In the summer and fall of 1981, Bonnie Raitt was enjoying the sunshine and good vibes in Malibu, Calif., recording her eighth album for Warner Bros. Records at Shangri-La Studios, a two-acre ranch up the hill from popular Zuma Beach. Audio engineer Rob Fraboni had converted the main house, which had been a bordello in the 1950s, into a recording studio at the direction of Bob Dylan and the Band after their 1974 tour.

In the summer and fall of 1981, Bonnie Raitt was enjoying the sunshine and good vibes in Malibu, Calif., recording her eighth album for Warner Bros. Records at Shangri-La Studios, a two-acre ranch up the hill from popular Zuma Beach. Audio engineer Rob Fraboni had converted the main house, which had been a bordello in the 1950s, into a recording studio at the direction of Bob Dylan and the Band after their 1974 tour.

By 1976, Fraboni and his business partners had bought the building and upgraded it to a full 24-track facility. The Band continued to do sessions at Shangri-La, and Eric Clapton later recorded his No Reason to Cry LP there. As Raitt told High Fidelity’s Stephen X. Rea, “I’ve been waiting my entire career to make this record, and I finally got the right band with the right producer in the right studio…I had a ball. Green Light is the first album I actually had fun doing…I tend to worry too much, to analyze and anguish over everything. That tends to make you look at things in a more serious framework. But then there’s the side of me that likes to let go and party all the time. It’s difficult to reconcile the two. Rob and the guys in the band helped to bring out the rebellious, crazy side of me.”

Warner Bros. was an artist-friendly label that was known for sticking with acts they liked and supported, giving them lots of opportunities to turn good recordings into commercial hits, but not applying a lot of pressure. Raitt would probably have already been dropped by most other labels, but she had a home: “I’m amazed that 200,000 or 300,000 people want to buy my record. I’m grateful that we draw as well as we do. All the people that come to see me year after year after year—I feel like I have a pact with them.”

Her previous album, The Glow, produced by the hitmaker Peter Asher, failed to meet expectations, with Raitt admitting she was “stung by the lack of response.” Inspired by the rootsy bands she was enjoying, including the Blasters, the Stray Cats and Rockpile, she intended to make an unabashed rock record. She told Rea, “There were inklings of the direction I was going in all along, when I started standing up at my shows about five years ago instead of sitting in a chair; when I began to play the Gibson instead of the acoustic, and then a Strat instead of the Gibson; when I moved my uptempo songs from the encore to the beginning of the set.”

Raitt found a readymade set of co-conspirators in the Bump Band, which featured ex-Faces keyboardist Ian “Mac” McLagan, guitarist Johnny Lee Schell, bassist Ray Ohara and drummer Ricky Fataar. They were signed to Mercury Records but could be imported as a unit, with additional players, like guitarist Rick Vito, organist William “Smitty” Smith or saxophonist David Woodford added as necessary.

As Raitt didn’t compose much, the songs were sourced from a smorgasbord of admired classics (the Equals’ “Baby Come Back”), nuggets from the eclectic catalog of NRBQ (“Me and the Boys” and “Green Lights”) an unrecorded Bob Dylan masterwork (“Let’s Keep It Between Us”) and other hot finds. Raitt co-wrote two of the LP’s 10 cuts, explaining songwriting wasn’t a priority: “I guess it’s a combination of laziness and lack of desire. I don’t spend any time at it. I don’t play guitar or piano for recreational purposes. I’m not a songwriter. I’m not a poet like Jackson Browne. I’m just not that good at it. Maybe I’d be better if I worked at it more.”

“Keep This Heart In Mind,” written by the fairly obscure Fred Marrone and Stephen Holsapple, leads off the album, and was unfortunately the disc’s initial failed single release. It has an infectious chorus, in which the singer insists that an ex-lover can always come back—a touching, if probably unrealistic, optimism. Raitt’s authoritative singing is buttressed by four backing vocalists, including Jackson Browne.

Eric Kaz, the highly respected songwriter for Raitt, Linda Ronstadt and many others, wrote “River of Tears.” Like “Love Has No Pride” and other heart-tuggers he wrote or co-composed, it features downcast lyrics: “Rivers of tears, oceans of heartbreak/I want to feel what your love can be/I close my eyes.” Unusually for Kaz, melodically it’s not a lament, but rather a midtempo groover. The Band’s Richard Manuel (who was living on the Shangri-La property at the time) sings harmony, and Raitt lays down her first impressive slide guitar solo.

Walt Richmond, pianist for Tulsa country-rockers the Tractors, co-wrote “Can’t Get Enough” with Raitt. A funky reggae beat merges with a guitar riff recalling both Ian Dury’s “Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick” and (when the saxophone enters), Average White Band’s “Pick Up the Pieces.” It’s a wonderfully rambunctious track that Raitt leads with enthusiasm. Fraboni and Fataar add some nice percussion.

Schell’s “Willya Wontcha” begins with a bang as his crisp guitar blends with Raitt’s slide and McLagan’s barrelhouse piano. Taken at a breakneck pace, it very much sounds like a hybrid Little Feat/Faces romp, with Schell singing parallel lines with Raitt like he’s Lowell George’s twin. Her slide solo midway is fiery. The lyrics are silly (“Willya wontcha do you dontcha really really wanna kiss me?/Honey it’s all right/I promise I won’t bite”) but who cares when you’re dancing around the room?

“Let’s Keep It Between Us” is an unrecorded Dylan song the bard offered to Raitt. Dylan had played it live on his autumn 1980 tour, but his own tour-rehearsal tape wasn’t released until 2021 on Bootleg Series Vol. 16. With a gospel drive characteristic of several of Dylan’s early ’70s songs like “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar,” it features a series of descending melody lines that the band absolutely nails. The interplay between McLagan’s piano and Smith’s organ couldn’t be better.

Raitt seems especially committed to the lyrics, about a (possibly interracial) couple defending themselves against the disdain of the world: “Back seat drivers don’t know the feel of the wheel/But they sure know how to make a fuss/Oh darlin’, can we keep it between us?” The bridge section adds an even more shocking aspect of the dilemma: “I know we’re not perfect, but then again, so what?/That ain’t no reason to treat you like a snake or to treat me like a slut/And it’s making me so angry.” In a career of great performances, this one may be Raitt’s most overlooked.

Raitt’s take of Terry Adams’ “Me and the Boys” follows the template of NRBQ’s 1980 original on their Tiddlywinks album, with its excitingly irregular rhythm intact and tons of room for hard rockin’ from the whole Bump Band. The groove is so like Rockpile it’s no wonder Dave Edmunds cut the song for his D.E. 7th album, which was released within a few months of Green Light.

Schell’s love of Keith Richards’ leading-from-the-rhythm technique is shown beautifully during the opening of “I Can’t Help Myself,” which he wrote with Raitt, Fataar and Ohara. The lyrics are a joyous celebration from the point of view of a woman who learned how to fall in love at an early age and never regretted it: “No matter how hard I try/I just can’t leave it alone/No use in wondering why/’Cause my heart has a mind of its own.” Vince Gill sings backup lines with Raitt and Schell.

“Baby Come Back” was originally a B-side for the multiracial British group the Equals’ single “Hold Me Closer” in 1967, before it returned as an A-side the following year as a worldwide hit (it peaked at #32 in the U.S.). Written by the band’s guitarist Eddy Grant, it grafted ska onto bubblegum pop, with a 4/4 beat that wouldn’t let go. The Bump Band arrangement replicates much of the original, including the spoken “all right”s and “yeah”s added by Bonnie’s big brother Steve.

Penned by the genre-bending Texan Jerry Williams (often known as Jerry Lynn Williams to avoid confusion with Jerry Williams Jr., a.k.a. Swamp Dogg), “Talk to Me” was included on his 1979 Warner Bros. disc Gone. Rick Vito’s guitar is added for Raitt’s version, to help it hit the spot between disco and Stax-style R&B. It’s a bit of a throwaway, but when the last 45 seconds are turned over to Woodford, it catches fire.

NRBQ originally cut “Green Lights” for their 1978 LP At Yankee Stadium, definitely not recorded at the baseball field, but with cover photos taken there as a birthday present for their bassist and Bronx Bombers fanatic Joey Spampinato. He wrote “Green Lights” with Terry Adams, and Raitt grabbed it for a fantastic conclusion to her “singular” LP. The band rocks mightily, but Fraboni and his engineer Tim Kramer botch part of the track, with Raitt’s voice too far back in the mix, with a vocal effect laid on it that screams “’80s” way too much.

Green Light was a solid enough album, but it didn’t break new ground commercially for Raitt. The record label began to admit she was never going to become the star she should be, and her contract was terminated in 1983 just after she turned in her next album, Tongue & Groove. In an extraordinary move, the label gave her the money to recut part of the album in 1985 (“I think at this point they felt kind of bad. I mean, I was out there touring on my savings to keep my name up, and my ability to draw was less and less”). Released as Nine Lives, it did nothing.

And then Capitol Records signed her, and she decided it was time to stop her sometimes over-the-top lifestyle. Raitt’s debut and “first sober album” for Capitol, Nick of Time, went to #1, and she won four Grammy Awards at the 32nd ceremony, three for that album and one for her duet with John Lee Hooker, “I’m In the Mood,” from his album The Healer.

Her time at Warner Bros. Records had been exhilarating, frustrating and highly creative, and her legacy there is still well worth exploring. She’ll kick off her next tour in August 2025. Tickets are available here and here.

Watch Raitt perform “Me and the Boys” live on Fridays in 1982

Raitt’s extensive catalog is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.