Bob Marley and the Wailers: Behind Their 1973 Capitol Records Session

by Harvey Kubernik The scene is Hollywood, October 24, 1973. International reggae pioneers Bob Marley and the Wailers are being filmed in a closed-door session at the Capitol Records Tower, by famed record producer Denny Cordell, who has captured the band recording 12 songs.

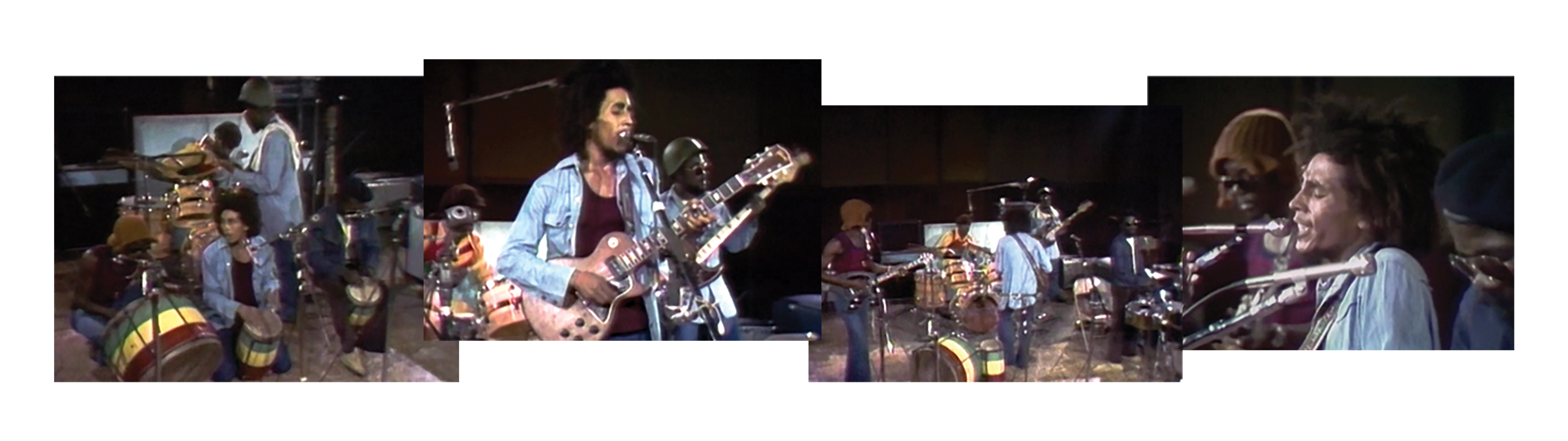

The scene is Hollywood, October 24, 1973. International reggae pioneers Bob Marley and the Wailers are being filmed in a closed-door session at the Capitol Records Tower, by famed record producer Denny Cordell, who has captured the band recording 12 songs.

Shot with four cameras and mixed “on the fly,” this footage, now colorized, has been painstakingly restored, resulting in an incredible presentation of this unseen live session.

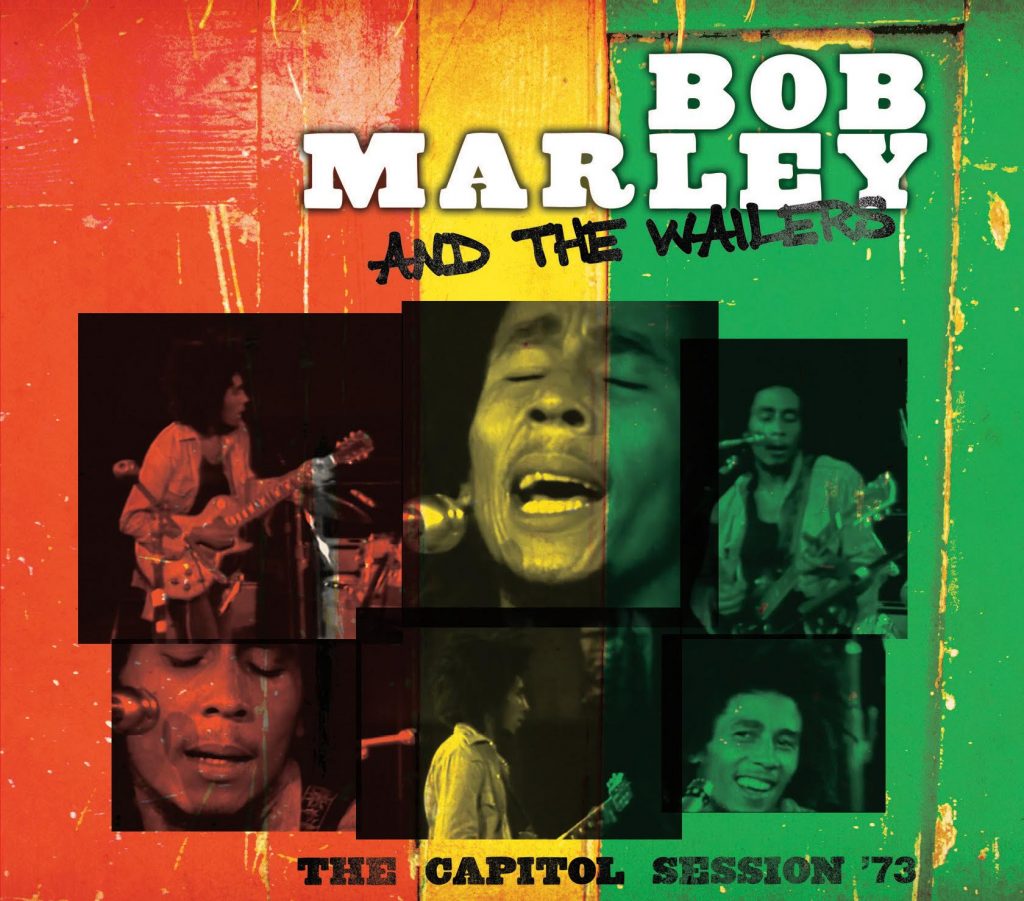

On September 3, 2021, Tuff Gong and Mercury Studios released this concert to the public officially for the first time as Bob Marley and the Wailers: The Capitol Session ’73.

Long-missing, the newly unearthed film captures a never-before-seen studio session with 12 performances by the legendary band, filmed and recorded live at Capitol Studios in Hollywood. Now restored and remastered, the footage from the session was recovered in a 20-year search of archives and storage units across the globe.

Watch a trailer for the film

This session at Capitol Studios represented a unique moment in the band’s career. Ten years after their formation, the Wailers had already logged several hits in Jamaica during the ska and rocksteady eras. Gaining recognition stateside, including a few shows with a still-unknown Bruce Springsteen at Max’s Kansas City in New York City, they then went on to tour with Sly and the Family Stone, before being unceremoniously dumped from the tour. This led to the band (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Joe Higgs, Aston Barrett, Carlton Barrett, Earl “Wya” Lindo) making its way to Hollywood to do this session.

Watch Bob Marley and the Wailers perform “Slave Driver” at the Capitol session

The footage from that day was considered lost until a freelance researcher uncovered a few frames. For more than 20 years, archives and storage units from New York and London to San Diego were tracked down and searched to retrieve fragments of the film, until it was fully unearthed, restored and remastered.

Evolving into a politically and socially charged unit after being inspired by the U.S. Civil Rights movement, various African liberation efforts and Rastafarianism, which Bob Marley and the Wailers studied from Rasta elders, their music reflected the soul and struggles of the era. Making poignant statements about life, liberty and social justice, the band imbued its sentiments into the songs, which are beautifully brought to life during this session.

Even in 1973, reggae music still had very little presence in the U.S. That had started to change with the December 1972 premiere of the movie The Harder They Come, starring singer Jimmy Cliff, as well as the soundtrack album from Chris Blackwell’s Island Records.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Live album

“In 1969, Jimmy Cliff’s ‘Wonderful World, Beautiful People,’ ‘Israelites,’ from Desmond Dekker and the Aces, and, a year earlier, Johnny Nash’s ‘Hold Me Tight,’ had received lots of radio airplay and sold records stateside,” remembers reggae scholar, author/DJ Roger Steffens.

“Nash had hired Bob Marley as a songwriter for his label and also a performer for JAD Records. So a lot of Marley songs had come out without anyone knowing who Bob Marley was. Nash struck later with ‘I Can See Clearly Now.’

“Then Michael Thomas wrote an article in June 1973 in Rolling Stone on the Wailers’ album Catch a Fire.”

In the fall of 1973, however, Marley and the Wailers were “in inner turmoil,” continues Steffens. “A few months earlier, co-founder Bunny Wailer, who had been raised as Bob’s brother since his father moved in with Bob’s mother in 1966, left the group. He was upset that Island Records’ chief, Chris Blackwell, told the group he had signed in late 1972 that he wanted them to tour ‘freak clubs.’

In the fall of 1973, however, Marley and the Wailers were “in inner turmoil,” continues Steffens. “A few months earlier, co-founder Bunny Wailer, who had been raised as Bob’s brother since his father moved in with Bob’s mother in 1966, left the group. He was upset that Island Records’ chief, Chris Blackwell, told the group he had signed in late 1972 that he wanted them to tour ‘freak clubs.’

“As I outlined in my recent book, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, Bunny’s response to that suggestion was to ask Blackwell what he meant by freak clubs. He said, ‘Well, you know, clubs where gals meet gals and guys meet guys and freak out. Drug business, all kind of stuff—freak. I said, ‘How you want to take us all in that direction? Why you want draw us down in dem kind of things? We is Rasta, we no stand for dem things.’ And Bunny quit the group on the spot.

“Coming off the critical success of their international debut on Island, Catch a Fire, Blackwell wanted them to tour America for their followup, Burnin’, which would prove to be the trio’s final work together.

“To replace Bunny, Bob invited the group’s initial teacher, the great Joe Higgs, known as the father of reggae music because of his early tutoring of many of the music’s initial stars. Higgs knew the harmonies and could play percussion, so he fit in perfectly as he rehearsed at the Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood that October.

“Outside the famous tower sat a mobile mixing studio, wherein sat a white American, harmonica player and fine artist, Lee Jaffe, who experimented with a brand-new special effects board while the rehearsal went on. Bootleg tapes of the event have circulated since the ’70s in collectors’ circles. But legal difficulties remained for decades.

“Ownership was claimed by Denny Cordell, who founded Shelter Records, and was championed throughout this period by a tireless British entrepreneur, Martin Disney, who was largely responsible for its ultimate release,” continues Steffens.

“Peter Tosh, who would leave the group too a few weeks after this film was made, is seen in an amazing duet with Bob on ‘Get Up, Stand Up,’ where he sings some different lyrics as if to trip Bob up. But this final alignment, after 10 years together, shows the tightness of their arrangements and how Bob was desperate to keep the Wailers’ sound alive. It was Bob who wrote the song, but he gave a verse to Peter to create so that he could share in the writers’ royalties. It was Tosh who wrote about being sick of the ‘bullsh*t game,’ and the mythology surrounding Jesus’ name,” adds Steffens.

“All in all, this refreshing new look at the [original] Wailers’ final days together will shed a welcome light on the power of their creations,” he continues. “I was angry for a long time that Chris [Blackwell] almost took joy in the fact that he helped break up the group. Over the years I’ve begun to think differently. Imagine the world without Bunny’s [album] Blackheart Man or Peter’s Equal Rights. We got three times the music we would have had if the group had not broken up.”

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.