The Beatles’ ‘I Saw Her Standing There’: Way Beyond Compare

by Colin Fleming There’s a tendency to think that the Beatles’ “serious” writing didn’t begin until the middle of their career, but from their very first album-opening moment, the Beatles revealed themselves to be gifted storytellers.

There’s a tendency to think that the Beatles’ “serious” writing didn’t begin until the middle of their career, but from their very first album-opening moment, the Beatles revealed themselves to be gifted storytellers.

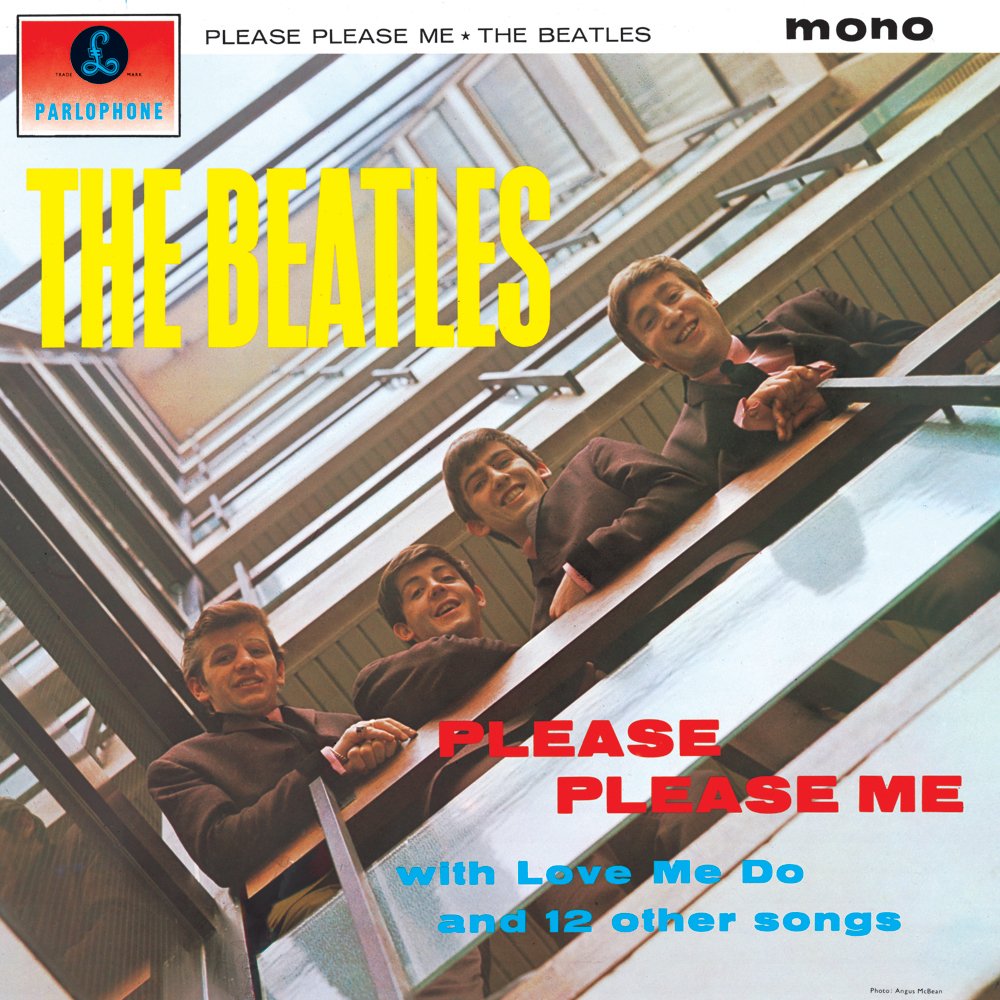

Please Please Me was Britain’s dominant long-player of 1963, a form of mini-Beatlemania. Hitting the top of the album charts in May after a slow, but persistent burn of a climb following from its March release, it remained locked in the premier position for 30 weeks, dislodged only by the group’s sophomore effort, With the Beatles, in time for the Christmas shopping season.

“Love Me Do” had come out as a single the autumn before, and was then joined by “Please Please Me” in the 45 rack a week and a half into 1963. Both songs appeared on the debut, but fans had those earlier discs. There was something else that sold Please Please Me and clearly kept it selling with its high “You need to hear this!” buzzy “it” factor.

We get evidence of that something else on Please Please Me’s first cut, “I Saw Her Standing There,” which also holds part of the secret of why The Beatles endure like the Beatles endure. The song was recorded at was then called EMI Studios in London on February 11, 1963.

The quality that makes “I Saw Her Standing There” a formidable work of authorship remains hidden in plain view these days. It’s as if one is taught to think, Beginning Beatles = Highly melodic but slight and Later Beatles = Weighty and artistic.

You don’t get a lot smarter than the Beatles were with this Paul McCartney-composed “potboiler,” a term favored by producer George Martin, and an apt descriptor for almost every opening song on every Beatles album, with the number formerly known as “Seventeen” representing the touchstone example that also proved a unique work.

Broadway songs were part of a story framework. They had a sort of narrative leg-up, for storytelling was a component of their birthright—why they were there in the first place. Rock and roll songs hardly ever told stories, though Chuck Berry was as much of a writer in a words-based sense as Walt Whitman (a poet-storyteller) or Mark Twain (a storyteller-poet), with his songs having the quality of diary entries from a roving, mercurial life.

Hearing a Berry song was akin to partaking of an audiobook—one that happened to feature the most exciting rhythm and blues in the background—with words that the author had originally written to himself. There isn’t as much of a jump from the Berry cuts on The Great Twenty-Eight to many entries in Thoreau’s journals as one might expect, save that the former details the urban milieu and the latter the rural.

You, a reader, could happen along and experience those journal entries and veritable journal entries, but it’s not as if their authors were taking you aside and saying, “Can we talk? I have to tell you something.“

We experience a form of intimacy with both Berry and Thoreau, but it’s also the intimacy of happenstance, of the found-text, the same way that reading the messages on a person’s phone may be.

The intention of complicity is the radical departure of the first few bars of Please Please Me. You and the Beatles were in on something together. One wasn’t just listening to the Beatles as makers of music; a friendship had started, with an immediate trust factor. The Beatles were in the room, you were in the room, and so was this binding agent of trust.

The people we are closest to are often those that we trust the most. The story of “I Saw Her Standing There”—and the language in which it is told—is a form of fast friend-making. Sometimes we have a friend before we know it. That tends to be how friendship works. Two kids enter the cafeteria at lunch during the school day as near-strangers, and emerge a half hour later as through-thick-and-thin buddies, believing they shall never be parted, though life, being life, always retains an attitude of, “Well, we’ll see about that.”

How did this transformation happen? One kid likely shared something with the other, and there was resonance, as well as gratitude for the sharing, which facilitates reciprocal sharing—or the feeling that one is welcome and safe to share if they wish—and the growing bond.

Nothing interests one person in another like a story well told. Stories are different that way. They’re not someone’s political beliefs, thoughts on the ballgame, comments about the weather or report about where they’re going for dinner. When the story is told with passion, we’re apt to be passionate. Our curiosity itself becomes an unbilled member of the dramatis personae.

We may also feel honored. That person chose us for the hearing of this narrative. Telling a story is a form of opening up one’s self. It’s not the average way of talking. If the story means a lot to the person doing the telling, it takes on greater meaning for us, too. Few emotions are more powerful than the one that drives the need to know more. That’s story, but at the most fundamentally human level.

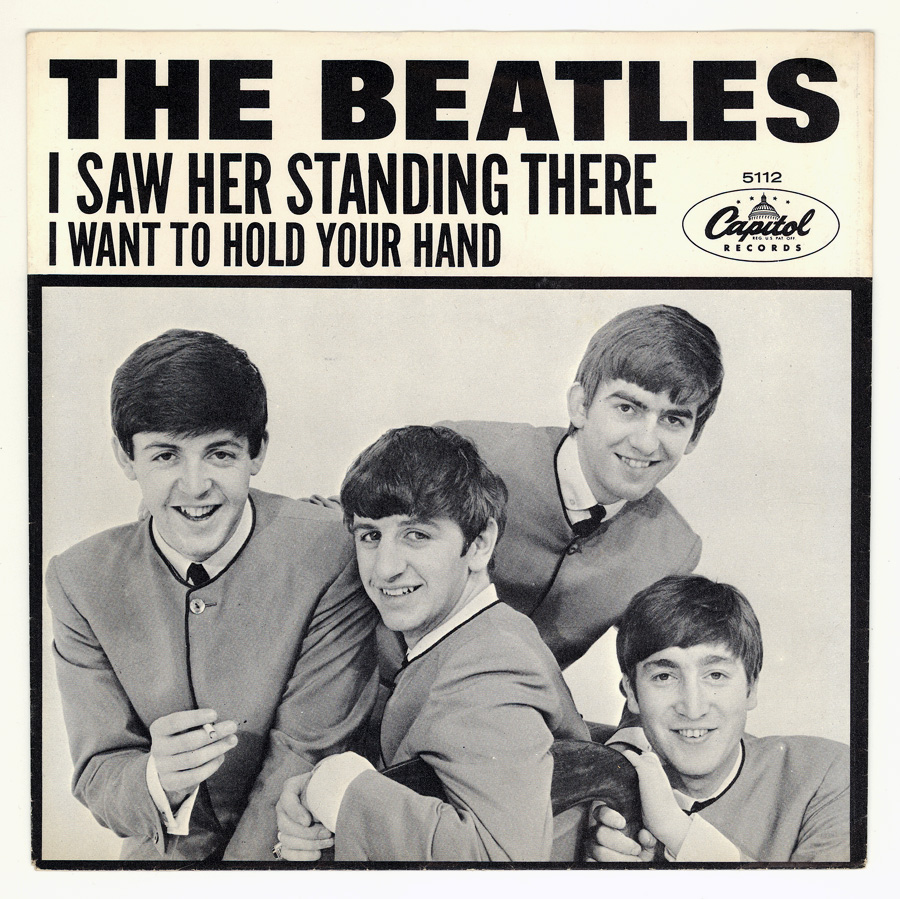

“I Saw Her Standing There” was the lead track on The Beatles’ debut album, Please Please Me.

“I Saw Her Standing There” is a story about being amazed. Teenage boys and young men play affairs of the heart close to the breast. They don’t effuse. To do so is to look less tough, generally regarded as inadvisable.

But the singer of “I Saw Her Standing There”—and we should note that this is a character in a story, not Paul McCartney, Beatle of Liverpool—doesn’t hold back. He makes no attempt to contain his excitement. His ardor—and his respect—become laws unto themselves of this burgeoning romantic land. Who cares if his mates might judge and joke? Some stories just need to be told.

The first word of the song is “Well,” with a comma following after it. We often use this construction to begin the answer to a difficult question. This version of “Well” is also akin to taking a deep breath at the edge of the diving board before up and going for it. Then the narrator gets into the meat of his tale and he starts fast, like the very best stories do.

“She was just seventeen, you know what I mean.”

We might think of this as the between-ness that is present in top-tier writing; there’s what’s said, what isn’t said, and a middle form of communication which is both wordless statement and intuited implication.

One line and we have three pronouns. We’re all involved in this drama. The enthusiasm overflows, but there’s a focused attempt to secure credibility with the next declaration: “And the way she looked was way beyond compare.”

Did you know any kids who talked in that fashion? And yet, there’s no artifice in the line. It tracks. This narrator picked the phrase up somewhere. Perhaps from a respected aunt. The point is, he’s choosing to use it now, because he wants us to trust him and this is a show of authority for a greater purpose.

If he does think in terms of conquest normally—as the ultimate goal of his efforts—he’s not doing so now. For this moment, he is a romantic, trying to elevate our eye lines, as he puts this person above others of his social circle and the constituents of the world he knows.

This young woman sounds remarkable on account of the sincerity we detect in the singer’s voice, and in the thought processes we can follow within his head. He’s trying to be exacting. You wouldn’t be exacting just for anyone. Then he does something startling. He asks a question.

“So how could I dance with another, when I saw her standing there?” It’s both a rhetorical device, and a gesture, a throwing up of one’s arms to the heavens, the fates, a cherub with a bow and arrow, and all but saying, “What do you expect me to do here? I’ve never known such feelings.”

The listener is a de facto friend, because the listener has been trusted with the telling of the tale. This storyteller is out in the open. He’s even appealed to the listener with the above query.

Listen to an early version of the song, from the Anthology 1 album

McCartney and the Beatles began this first album with a story that was tantamount to a young person baring their soul, with something that matters to a young person. And, frankly, something that matters to people of all ages, whether they’re looking back with fondness and gratitude, or hoping to move forward and locate that—and whom—for which they long.

The Beatles had us after that first verse. We were with them. The action proceeds. A heart goes no less than “Boom!” but there is no need for a defibrillator. The girl looks at the singer, and his eyes meet hers. He doesn’t employ that phrase, but he does employ a brilliant little pun by using the pronoun “I” twice (i.e., two eyes).

“And I, I could see.” He’s all but been split in two. He may have also encountered, for the first time, his better half.

John Lennon would also take the “I” pronoun on “There’s a Place,” the penultimate song on Please Please Me, and convert it into no less than four syllables to emphasize the interior world of the individual. The Beatles text-painted like Handel when they were at their best, and they got to their connective best very early.

The singer of “I Saw Her Standing There” is thinking in terms of temporality himself; it’s like he’s counting out every last grain of sand in the hourglass and savoring the flakes of this evening the most.

“And before too long, I fell in love with her,” he tells us. The story hops along, but it’s also a confessional, not for a sin, but an outpouring of joy. The storyteller has to tell his story. It’s as if it tells him—the person he is, the person he is becoming.

Listen to a live version of “I Saw Her Standing There” from the BBC

We have no idea how the romance will work itself out. It’s possible that this story is the story of an evening—an enchanted evening.

Some romances—and connections—are meant to last but several hours in real time, but live for the rest of one’s life in mind and memory. That doesn’t make them less viable.

“I Saw Her Standing There” is itself an endless (and endlessly relatable) story in one sense, but also a finite one in that it moves through its action in less than three minutes.

The pot didn’t just boil—it sold us on the power of story. Not that we ever really need to be sold on story’s power. We simply have to be put in the position to hear the story that someone has to tell.

For the Beatles, that particular position was right at the beginning of their first album. And before too long—well, you know the rest.

Watch the Beatles perform the song on The Ed Sullivan Show

Related: The same author wrote a feature about The Beatles recording of “Mr. Moonlight”

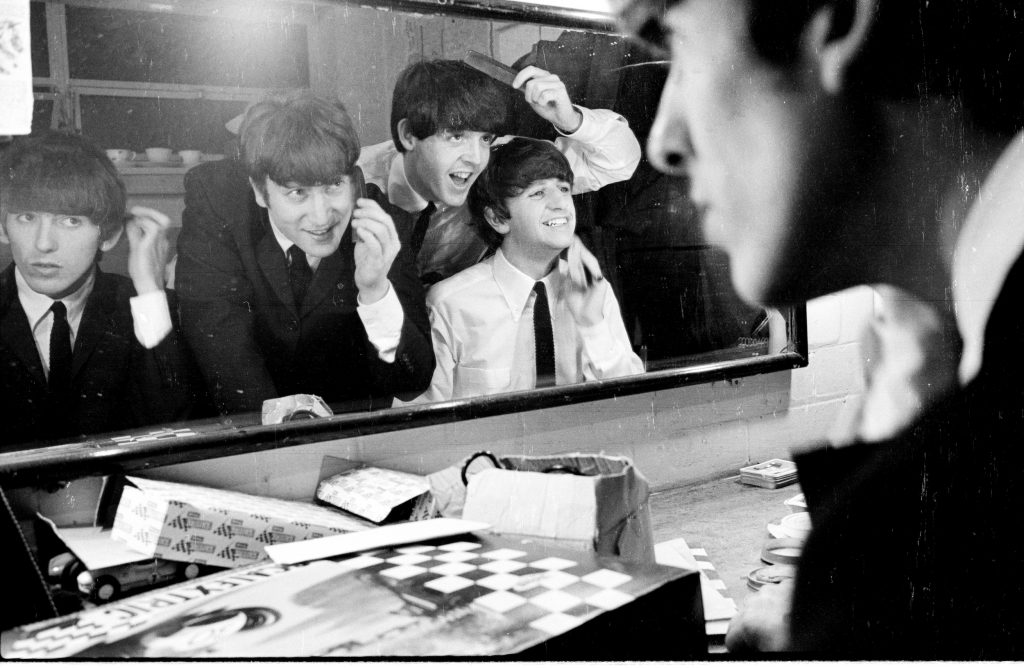

McCartney documented The Beatles’ 1963-64 days in a photo book, available here. The Beatles’ “red” and “blue” albums were upgraded in 2023. They’re available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. The Beatles: 1964 U.S. Albums In Mono are in a 2024 eight-LP boxed set available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

The 12-LP and 8-CD editions of the Beatles’ Anthology Collection are available in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Anthology 4 is available as a standalone 3-LP or 2-CD set in the U.S./worldwide here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

5 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThis was the first 45 record I ever bought. I remember it clearly, and it started me down a long road of playing and loving rock ‘n roll that continued for the next 50 years. Thank you, Beatles. You were the absolute best.

Any analysis of this song cannot be considered complete without considering that McCartney originally intended the opening lines to be “she was just seventeen, and she’d never been a beauty queen.” IIRC, John suggested the change to “You know what I mean” even though Paul wasn’t confident that one would know what one meant.

talk about great storytelling… good job, colin!

Chuck Berry? Paul admitted he got the bass line from “I’m Talking About You”.

My favorite song from the “early” era. Not to mention I have the framed Michael McCartney photo of John and Paul working on the song in Paul’s boyhood home…a spot I got to stand in on a tour in Liverpool.