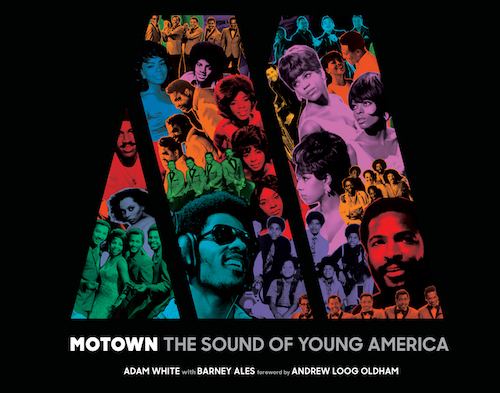

A stunner of a book, described—accurately—in its jacket as “the definitive visual history” of Motown, is indispensable for anyone interested in the label’s history, its business dealings, how it paralleled America’s political, economic and social events in the ’60s and its impact on pop culture. Motown: The Sound of Young America is authored by longtime music industry writer, editor and executive Adam White with Barney Ales, for years the influential label’s #2 exec to its founder, Berry Gordy Jr. The book, from Thames & Hudson, was published in 2016. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

The 400-page hardcover book features over 1,000 illustrations, many of which span across two pages, gorgeously devoted to so many of the revered label’s much-honored subjects including Marvin Gaye, the Jackson 5, the Supremes, the Temptations and more. Dozens of original album covers and single sleeves are also included.

The Temptations, The Miracles, Stevie Wonder, Martha & the Vandellas and The Supremes at EMI Records in March 1965, for the U.K. launch of the Tamla-Motown label. (Photo: Paul Nixon Collection; used with permission)

While pictures of the stars and their recordings will be considered the main attraction of Motown: The Sound of Young America for some, it’s White’s and Ales’ exhaustive knowledge of the Motor City label that offers readers a unique behind-the-scenes look at Motown. They answered some questions for Best Classic Bands.

As a Motown expert, can you share some of the more surprising revelations that you discovered while researching the book?

Adam White: The surprises mostly came in the form of detail about, and insights into, the people who worked there: the “backroom believers,” as I call them. Such as the time that my collaborator on the book, Barney Ales, who is white, effectively desegregated one of Detroit’s top restaurants when he and Berry Gordy—and their wives—went to the London Chop House some time in 1961, to be told at the front desk, “We don’t serve colored people.” Barney shot back, “That’s good, because we don’t eat ’em.” This may sound like a music hall joke, but clearly it wasn’t. Anyway, because Barney knew the owner and told the woman at the desk to check with him, the four of them were soon seated. A friend of Barney’s who was already inside sent over a bottle of champagne by way of congratulation.

Then there was George Schiffer, the Viennese émigré who handled Motown’s legal affairs, who—upon meeting someone for the first time—would hand them a copy of Mao Tse-tung’s “little red book.” Can you imagine the confusion that must have caused for the recipient? Was Motown a communist organization? Those are the kind of revelations which appealed to me.

Another example concerned the time when Berry’s second wife bootlegged copies of Mary Wells’ “My Guy” hit in 1964. I knew that had happened, but didn’t know how one of the music industry’s most controversial figures, Morris Levy—who had connections to organized crime—was involved. Getting below the surface of incidents like that proved satisfying.

You had told me many times about “the Motown book you were working on.” When I finally saw it at my local bookstore and started thumbing through it, I was blown away by the enormity—and majesty—of it. The book jacket indicates that there are over 1,000 illustrations. Can you describe how the book evolved in its scope? And how many times that changed (upwards)?

AW: The original aim was to tell the story of the men and women who helped Berry to build and expand his business from the beginning. The most important of these was Barney, who joined full-time in 1961 to get the records played on the radio and the company paid by its distributors. Without those achievements, Motown arguably would never have become the commercial, cultural powerhouse that it did.

There’s been so much written about Motown over the years—especially about the artists, songwriters and producers—but relatively little about the backroom believers. Barney and I wanted to add to the sum of knowledge about the company, rather than repeat what’s already been documented. The music is Motown’s primary legacy, of course, and rightly so, but there was more to its accomplishments than that.

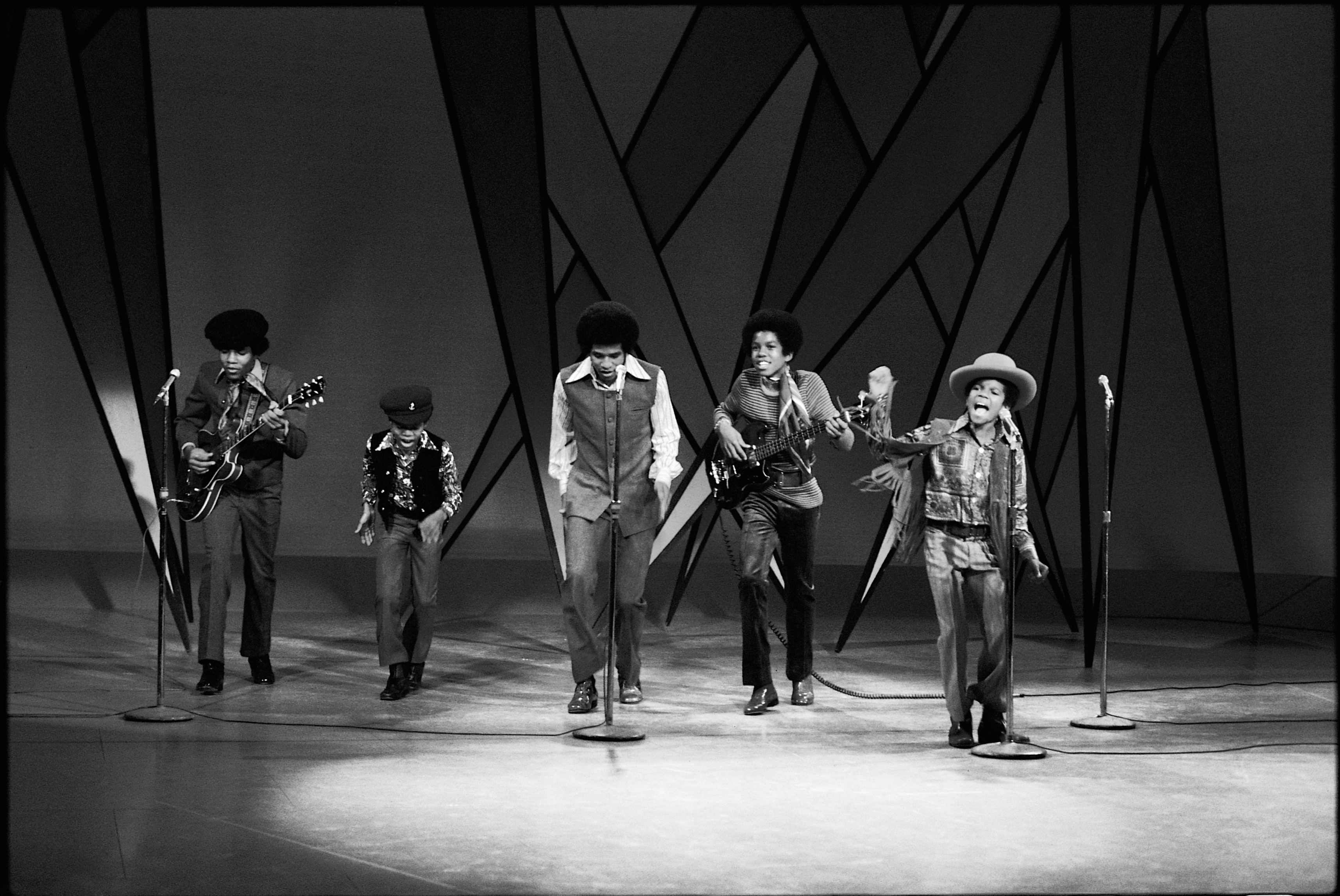

When I met with Thames & Hudson, they suggested a fresh approach: augmenting the narrative with visuals, and illuminating the story by using the power of images. After all, it was the look, style and choreography of the Motown artists—the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, the Jackson 5—which made them stand apart. And which made them so attractive on television, which played a central role in bringing the music into America’s living rooms.

The Jackson 5 make their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in NYC, December 14 1969 (Photo via Motown Records Archives via EMI Archive Trust and Universal Music Group; used with permission)

Knowing that we had access to photos from Barney’s own collection, and to Motown archive photos through Universal Music, Thames & Hudson’s idea sounded good, and it was “official” because of Universal’s cooperation. I originally had more text with Barney, but it must be said: a great picture is worth 1,000 words. Nothing like this about Motown has been done so extensively and colorfully before.

What Motown recordings do you find yourself playing the most?

AW: That’s almost impossible to answer, because there’s so much music. Personally, I was hypnotized by Motown’s 1963 output, like Marvin Gaye’s “Can I Get A Witness” and Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave” or Mary Wells’ “You Lost The Sweetest Boy” and the Supremes’ “When The Lovelight Starts Shining Through His Eyes.” But then you must consider the innovation of 1966, with the Four Tops’ “Reach Out I’ll Be There” and Jimmy Ruffin’s “What Becomes Of The Brokenhearted,” to name just a couple of extraordinary records. I go back to those two years, more often than not.

Then again, “What’s Going On” is extraordinary. Like some others devoted to Motown from the early days, I found it difficult to adjust at first to the concept and texture of the album. But soon enough, I found it as compelling as anything before or since—and it’s music to be played forever.

BCB was able to ask Barney Ales an insider question.

Ales has been described as Gordy’s indispensable right-hand man since he was handpicked by the legendary figure to join the label in 1961 as national sales manager and radio promotion director. And while its Gordy who was the logical face of Motown alongside its stunning array of stars, it was often Ales, a white man at a company synonymous with black music, who presented Motown’s new recordings to record retailers and radio stations as head of the label’s day-to-day operations. He ultimately rose to become Motown’s president.

Stevie Wonder had eight #1 solo hits. Five additional singles—that I believe to be as good as any he recorded—were big hits but didn’t reach #1 on the Hot 100: “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” (#3 in 1965), “I Was Made to Love Her” (#2 in 1967), “For Once in My Life” (#2 in 1968), “My Cherie Amour” (#4 in 1969) and “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours” (#3 in 1970). Can you take our readers back to working any of those and share anecdotes of the week when you knew they weren’t going to make it to #1?

Barney Ales: Was there a moment when I thought any of those Stevie records might not make #1? It didn’t matter, I just kept on pushing, and I kept on pushing my promotion team. You kept going for as long as you could, just like in football. Besides, the chart people at the trades would never tell you when a record was going down. And the hits were still selling even if they were going backwards. They were still getting played by radio stations. You never gave up.

OK, so there are a couple of other factors. Stevie’s ballads, like those written by Ron Miller, had a different flavor. I’m thinking of, say, “My Cherie Amour.” A ballad like that may be more popular in the long run, but in the short-term, it’s tough to compete against a rock-oriented or uptempo tune like Zager & Evans’ “In The Year 2525” or “Spinning Wheel” by Blood, Sweat & Tears.

Related: Motown covers Motown – Our feature on classic “double dips”

Barney Ales presents Gold Record awards to Marvin Gaye (Photo courtesy of Barney Ales; used with permission)

With Stevie’s “For Once In My Life,” the #1 record that was up against was one of ours: Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” It was just a monster, no getting away from it. Nothing was going to move that mother, week after week after week. But I think Stevie probably forgave Marvin. It was all in the family.

What are some of the most prized Motown recordings in your collection? (They don’t necessarily have to be rare… but perhaps simply meaningful to you.) Were many friends and colleagues looking out for you—for decades—and sending you unexpected items? Do you have any garage sale/flea market stories where you were surprised to find a needle-in-a-haystack item?

AW: Well, “Heat Wave” is certainly among the most prized, because it was the first Motown record I ever bought. The Four Tops’ “Ask The Lonely” is another, because it reflected the depth and soul of Levi Stubbs’ voice like nothing else. I couldn’t believe one record was capable of capturing such emotion, and it made me revere the Tops above all others. Then, the best show I ever saw in my life was their first concert in Britain in November 1966, at the Saville Theatre in London.

Friends certainly came to know—and tolerate—my devotion to Motown, but they also knew to check with me first about anything they saw in a secondhand store or garage sale, because I had quite a lot of stuff. But my all-time greatest find was Tamla 101—the very first release on the label from early 1959, “Come to Me” by Marv Johnson. Berry licensed this to United Artists Records after it first came out in Detroit, so the Tamla version is quite rare. When working for Billboard, I was at a record retail chain’s annual convention near Pittsburgh, and had the afternoon off. A friend and colleague—Fred Goodman, later the author of Mansion on the Hill, among other great books—and I went to visit nearby Johnstown. There was a record store, selling new and secondhand releases, and there, for two bucks, was a copy of “Come to Me.” I felt like I had died and gone to heaven.

Finally, since we’re talking about artists—who in many cases are still active—are there topics that have occurred that you would love to have included had your deadline been today? Conversely, can you tell us about some 11th hour “gets”… whether they were interviews, photos, etc.?

AW: I wish there had been more time and space to write about Motown’s music publishing arm, Jobete, because in many ways, that’s been the most valuable and enduring part of the business. You still hear those songs today, hugely popular on streaming services and featured in all sorts of places through sampling, TV, film, sync use, on stage and so on. Many of these will last long into the future. Because Berry had started out as a songwriter, he knew the value of music copyrights. And when he finally sold Jobete, he netted more than five times the amount he had earned by selling the record company previously. I’d like to have delved deeper into Jobete.

An eleventh hour “get”? Those candid photos of the artists and musicians backstage at London’s Finsbury Park Astoria theatre, before the opening show of the Tamla Motown U.K. package tour of 1965. Because most of the artists were hardly known to British audiences, the photos weren’t published at the time. We found them through the Victoria & Albert Museum, because the family of the photographer had donated them to the V&A after his death. I defy you to find more evocative photos than those.

Ales died April 17, 2020, of natural causes, in Malibu, Calif., at age 85. He was born Baldassare Ales and grew up in northwest Detroit. “I liked Barney right off the bat,” Smokey Robinson told Adam White. “He was a very straightforward kind of guy, not a bullsh*tter or anything like that. Especially for me, being a kid, he seemed to know what he was going to do. I was amazed how he knew everybody.”

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.