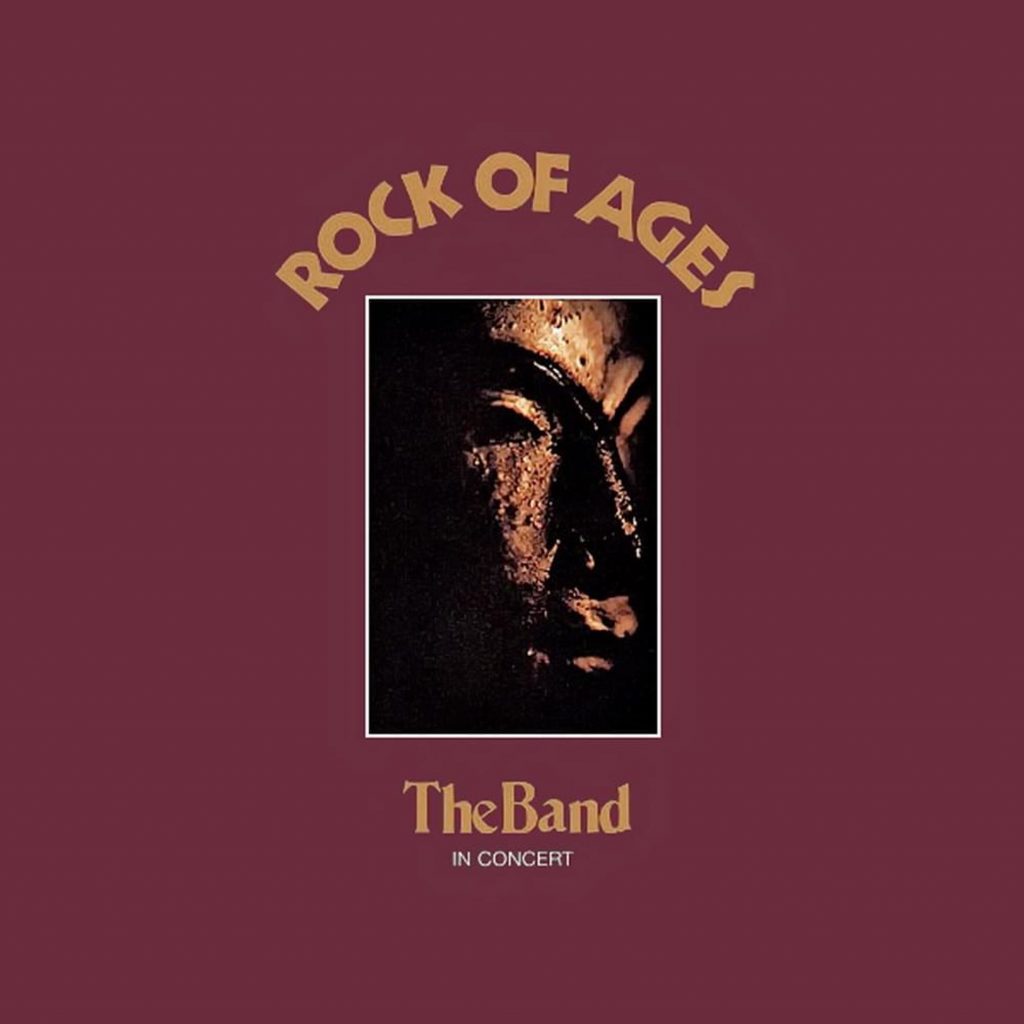

Recorded over the last four nights of 1971, The Band’s Rock of Ages belongs on any short list of the best live albums ever committed to tape, while serving as a coda to the group’s groundbreaking influence on musicians on both sides of the Atlantic. The original release documented peerless musicianship with state-of-the-art clarity, elevating their best material with expanded arrangements on a carefully edited and sequenced double LP that would serve as a capstone for their defining chapter during their four years based in Woodstock.

Recorded over the last four nights of 1971, The Band’s Rock of Ages belongs on any short list of the best live albums ever committed to tape, while serving as a coda to the group’s groundbreaking influence on musicians on both sides of the Atlantic. The original release documented peerless musicianship with state-of-the-art clarity, elevating their best material with expanded arrangements on a carefully edited and sequenced double LP that would serve as a capstone for their defining chapter during their four years based in Woodstock.

At that point in their career, the Canadian/American quintet found itself on the cusp of creative fatigue after more than a decade together since their scuffling days as the Hawks, backing rockabilly wild man Ronnie Hawkins, and their trial-by-fire backing a plugged-in Bob Dylan on his infamous 1966 tour. That seasoning undergirded the unhurried power of their playing and the thematic maturity of their stunning 1968 debut, Music from Big Pink, and the earthy alchemy of their eponymous successor a year later. Taken together with the rough drafts of Dylan’s “basement tapes,” those two albums changed the course of rock by tracing folk, blues, country and gospel fault lines that would anticipate the roots renaissance of Americana decades later.

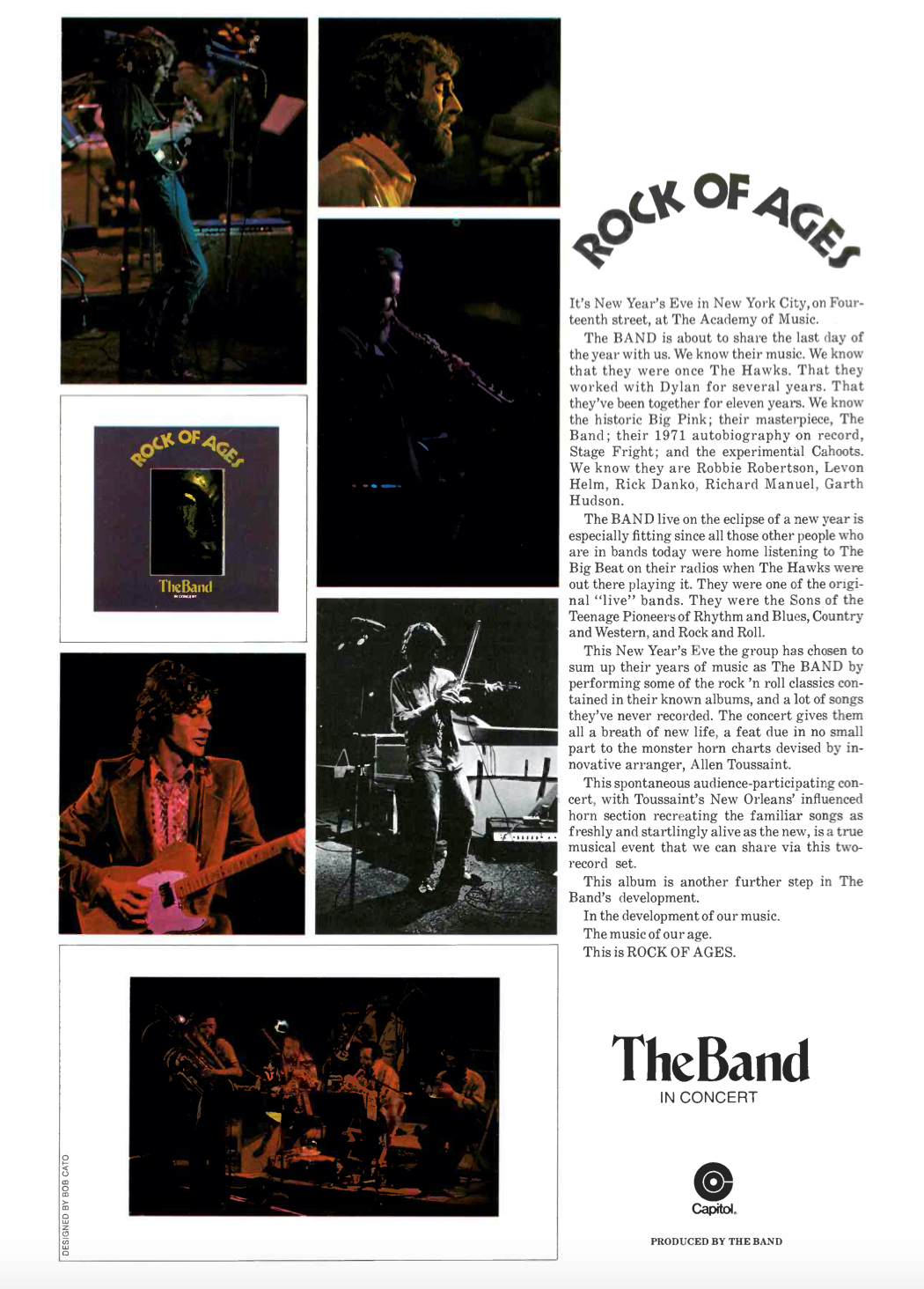

Bob Dylan with The Band, Dec. 31, 1971, at NY’s Academy of Music (Photo © Ernst Haas via Iconoclast and UMe)

Big Pink and The Band clinched the Band’s headlining status while raising lofty expectations at a time when an emerging rock press and FM radio sought more than seven-inch earworms. Their third studio album, 1970’s Stage Fright, drew mixed reviews and a general sense of disappointment despite its success on the album chart, reaching #5 even as critics lamented the studio polish and slighter material on offer.

The songwriting collective forged during their sojourn with Dylan had withered, leaving guitarist Robbie Robertson to emerge as principal writer, generating friction with his partners, especially erstwhile Hawks leader Levon Helm. Sessions in early 1971 for the next album, Cahoots, found Robertson straining lyrically, his weakest lyrics succumbing to dogmatic musings.

The Cahoots sessions did serve up one song that rekindled a musical dialogue between Robertson, Helm and Rick Danko. In “Life is a Carnival,” the trio devised a slippery, off-centered rhythm track of guitar, bass and drums bubbling with syncopations that pointed south toward New Orleans. The Band’s members were fans of Crescent City R&B, especially the rich catalog of songwriter, arranger and producer Allen Toussaint, whose sophisticated funk reached a pinnacle the previous year with Lee Dorsey’s classic Yes We Can album. Robertson approached Toussaint to arrange horns for the track, to which he responded with intricate brass and reed parts that bypassed conventional block chords, lobbing an antiphonal volley of horn lines that bounced off the rhythm section in a giddy, sonic kaleidoscope that would open the finished album.

With album tracks completed, the Band resumed touring behind Stage Fright, heading for Europe for their first concerts since the ’66 tour that subjected them to abuse from audiences outraged by Dylan’s rock ’n’ roll apostasy.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Stage Fright

Any trepidations about a similar reception were banished from the first show in Hamburg, with the group energized by the ecstatic response: The Band was playing in peak form every night, feeding off the audiences’ energy in 10 cities, including two triumphant nights at London’s Royal Albert Hall, notoriously (if incorrectly) cited as Waterloo for Dylan and the Hawks five years before.

That reception proved restorative as they headed back to America and a string of summer festival dates, followed by a fall tour culminating in four nights at New York City’s venerable Academy of Music. With renewed confidence in their playing, the prospect of a live album offered a chance to cement their onstage stature at a time when remote recording technology and concert sound reinforcement afforded a new level of commercial and critical viability for live albums. Since 1969, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Cream and the Allman Brothers Band had all delivered powerful live sets that only burnished their careers. Now it was the Band’s turn, and they were determined to make their first live album more than a souvenir or a stopgap.

The Academy dates would provide four consecutive shows to get things right technically and musically, in a venue built as a 19th century opera house. A customized remote recording van with 16-track tape machines was booked, with Phil Ramone set to engineer.

With Cahoots about to hit the street and Toussaint’s raucous contribution fresh in their ears, the Band recruited him to craft bespoke arrangements for 11 of the night’s songs, including “Life is a Carnival.”

Toussaint’s impact is spotlighted from the downbeat, juggling the shows’ running order to effectively start with the second set and Robbie Robertson’s introduction of the five “best horn men in New York” joining the Band. An expectant hush gives way to Rick Danko’s elastic fretless bass riff leading into the now 10-piece ensemble’s cover of “Don’t Do It,” a 1964 Marvin Gaye hit energized by a rowdy lead vocal from Helm and Danko’s bounding bass, which surpasses the original part from legendary Motown bassist James Jamerson.

The song sequence then turns toward the strongest songs in the group’s quiver, with “King Harvest (Must Surely Come),” the simmering closer to The Band, paced by Richard Manuel’s clenched vocal and Robertson’s tart Telecaster figures against the elegant backdrop of Toussaint’s horns.

In concert, the Band left little to chance, adhering to fixed song lists and hewing closely to arrangements memorialized in the studio—there were no long jams, impromptu medleys or grandstanding solos save for Garth Hudson’s nightly freak-out on his hot-rodded Lowrey organ, originally gene-spliced from Bach as the intro to “Chest Fever” and now titled “The Genetic Method.” Instead, they played concise songs highlighting their versatility as multi-instrumentalists: Manuel could move from piano bench to drum stool while Helm played mandolin or electric guitar; Danko would unstrap his bass and pick up a fiddle; and Hudson moved freely between keyboards, accordion and saxophones. As for the era’s arms race between bigger, louder P.A. systems, the Band favored quieter, clearer stage mixes revealing their instinctive ensemble interplay.

Rock of Ages offers two other new songs, including an unreleased Robertson original, “Get Up Jake,” and the closing rave-up of Chuck Willis’ “(I Don’t Want to) Hang Up My Rock ’n’ Roll Shoes),” a 1958 B-side foreshadowing the Band’s affectionate oldies tribute, Moondog Matinee, a year later. Otherwise, the setlist leaned into Big Pink and The Band’s atmospheric songs to satisfying effect on future classics “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” now linked in a familiar segue to the second album’s opener, “Across the Great Divide.”

The original two-LP collection was released on Aug. 15, 1972. The Band’s stature as a superb live band would ultimately be documented on six albums from the original quintet, plus three expanded editions, including a 2001 two-CD edition of Rock of Ages, a further expansion and remix from the same Academy concerts, and an expanded deluxe edition of The Last Waltz, their 1976 all-star big screen sendoff. Add their live recordings with Dylan (including 1974’s Before the Flood double set and a whopping 36-disc CD box documenting Dylan’s 1966 tour) plus six live sets featuring the regrouped lineups following Robertson’s departure, and the legacy of their live shows is substantial.

Yet there is strong evidence to cite 1971 as the Band’s peak year onstage, with Rock of Ages their formal bid for posterity. A second CD’s worth of material from the 2001 remastering approaches a more complete record of the New Year’s Eve show estimated as source for 80 percent of the material on the album, including three loose-limbed performances with surprise guest Dylan, which fill out the repertoire without improving on the original 19-track version.

What does buttress the case for ’71 as zenith is the Royal Albert Hall concert captured in June at the Band’s request after their triumphs in Germany, Austria and France. EMI (then owner of the Band’s label, Capitol) brought four-track tape machines to the venue with a complete 20-song set captured, if only for posterity. Sonically, the RAH tapes could not approach the pristine mixes Phil Ramone would pull from December’s 16-track coverage.

BONUS AUDIO: Hear “The Shape I’m In” from The Band’s June 1971 concert at the Royal Albert Hall, released with the 50th anniversary remixed and re-sequenced Stage Fright.

What the Albert Hall show does offer is the core quintet playing with a muscular urgency that often surpasses Rock of Ages, their tougher material taken at a faster pace and the vocals on their more confessional material (especially “The Shape I’m In” and “Stage Fright”) almost feral in projection.

This ad appeared in the Sept. 9, 1972 issue of Record World

By contrast, the December performances sound deliberate and even cautious, if beautifully rendered, a likely consequence of having had only a day to rehearse the added horn section playing Toussaint’s elegant charts. The original EMI tapes may have been deemed too muddy for commercial release, but Bob Clearmountain’s remix retrieves detail that was likely unattainable with 1971’s gear.

Taken together, the London and New York live recordings afford a last look at the Band as they rang out 1971 and headed into what would later be regarded as the “lost” year of 1972, following Dylan out of Woodstock and across their own great divide to Malibu and a period of dissolution and disillusionment. Four years later, the original incarnation of the Band would disband, following The Last Waltz.

[The Band’s recordings, including Rock of Ages and many expanded editions, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

BONUS VIDEO: Watch the Band perform “Don’t Do It” live at New York’s Academy of Music on December 31, 1971

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationGlad to see you mention the Royal Albert Hall CD.

I was at one of those two gigs (IIRC the second) and it was truly spectacular.

Although I bought Rock of Ages as soon as it was released (and the CD reissue) I always found it somewhat disappointing.

Hearing the Albert Hall recording properly (as opposed to the dimly-recorded Royal Albert Rags boot) simply underlines the reason. Nice though Toussaint’s arrangements were I feel it was a mistake for their first live recording not to be just the five of them – just compare Don’t Do It on the two sets: the RAH rocks so much harder.

And Rick Danko’s Loving You (etc) was a highlight that I kept in my mind for decades.

For me this CD is THE finest live recording of the Band, period.

Appropriate that you should publish this right before New Year’s Eve. Garth’s “Genetic Method” ultimately breaks into “Auld Lang Syne” (before going into “Chest Fever”) and so listening to that performance has become a New Year’s tradition for me.