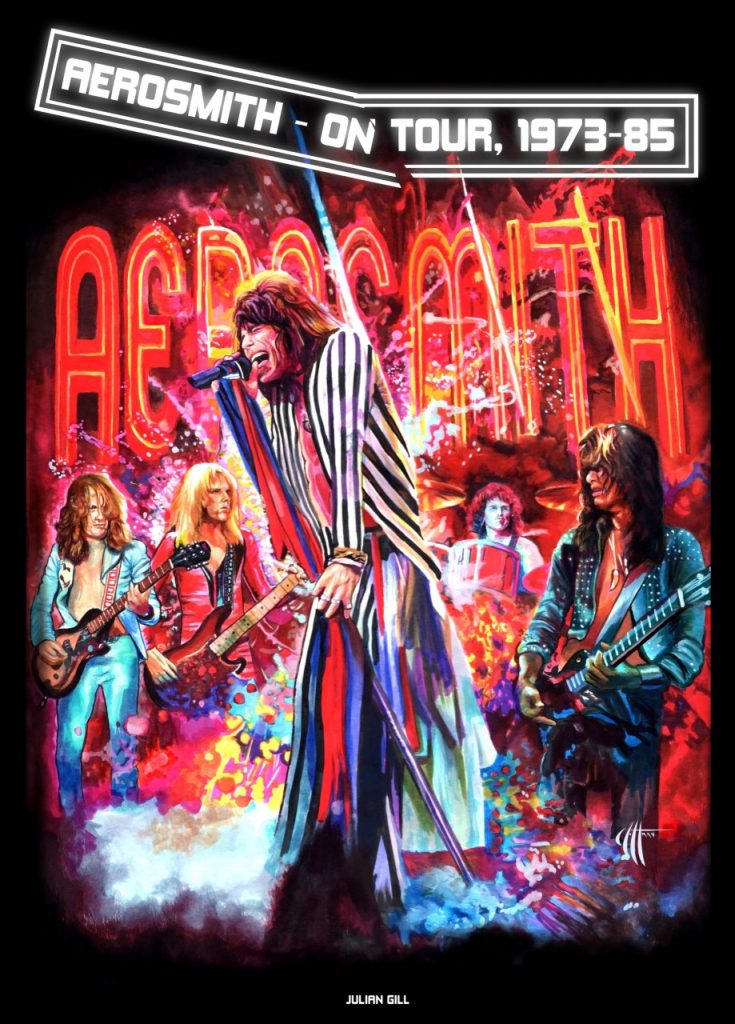

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the formation of the classic Aerosmith lineup—Steven Tyler, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Hamilton and Joey Kramer—a new book, Aerosmith On Tour: 1973-1985, exhaustively chronicles for the first time the band’s career on the road, from early gigs in high school auditoriums and ratty clubs to headlining arenas and stadiums. Written by Julian Gill, Aerosmith On Tour: 1973-1985 unveils its tale via local reviews, eyewitness reports, press accounts and interviews with key insiders.

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the formation of the classic Aerosmith lineup—Steven Tyler, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Hamilton and Joey Kramer—a new book, Aerosmith On Tour: 1973-1985, exhaustively chronicles for the first time the band’s career on the road, from early gigs in high school auditoriums and ratty clubs to headlining arenas and stadiums. Written by Julian Gill, Aerosmith On Tour: 1973-1985 unveils its tale via local reviews, eyewitness reports, press accounts and interviews with key insiders.

The following excerpt from the book recalls the band’s earliest days as a performing outfit. We’ve reprinted it here with permission from the publisher, the author and publicist Ken Sharp.

***

Joey Kramer: “There are bands that are really terrible that are making a million dollars. There are bands that are really good that are making no money. It’s all a matter of chance. No matter how good you are, you have to be lucky to a certain extent” (Boston Herald, 9/16/1973).

Clones of the Stones or heirs apparent to Jim Morrison or a neo-Dead-End Kids? It ultimately matters not a damn; a half-century of music stands as solid testament to a Boston group that became America’s band. In popular culture, the Dead-End Kids were a group of menacing New York City street kids. Punks, in other words, though that term would be appropriated for a style of music that had emerged from the garages of disaffected youths in the late ’60s. Early acts wearing the label, willingly or not, included the MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges, with the latter particularly having taken inspiration from the Stones but transformed it to the point of being nearly unrecognizable (apart from a few unfortunate physical analogues). Where the nihilism of the Velvet Underground broke from direct connections with the Warholian art scene, the emerging glitter movement of the early ’70s was firmly rooted in style, performance and attitude not always translating into quality. Aerosmith’s goals were simple: To get off playing music and to get people off to their playing. Though [guitarist] Joe Perry also wanted to play loud, pushing the levels until he could see the sonic waves, much to the chagrin of [vocalist] Steven Tyler. The battles were present from the beginning, and conflict and tension fueled Aerosmith to the heights of stardom and popularity while slowly poisoning the band’s very soul.

Clones of the Stones or heirs apparent to Jim Morrison or a neo-Dead-End Kids? It ultimately matters not a damn; a half-century of music stands as solid testament to a Boston group that became America’s band. In popular culture, the Dead-End Kids were a group of menacing New York City street kids. Punks, in other words, though that term would be appropriated for a style of music that had emerged from the garages of disaffected youths in the late ’60s. Early acts wearing the label, willingly or not, included the MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges, with the latter particularly having taken inspiration from the Stones but transformed it to the point of being nearly unrecognizable (apart from a few unfortunate physical analogues). Where the nihilism of the Velvet Underground broke from direct connections with the Warholian art scene, the emerging glitter movement of the early ’70s was firmly rooted in style, performance and attitude not always translating into quality. Aerosmith’s goals were simple: To get off playing music and to get people off to their playing. Though [guitarist] Joe Perry also wanted to play loud, pushing the levels until he could see the sonic waves, much to the chagrin of [vocalist] Steven Tyler. The battles were present from the beginning, and conflict and tension fueled Aerosmith to the heights of stardom and popularity while slowly poisoning the band’s very soul.

Nipmuc Regional High School, site of Aerosmith’s first paying gig (Photo by Julian Gill, used with permission)

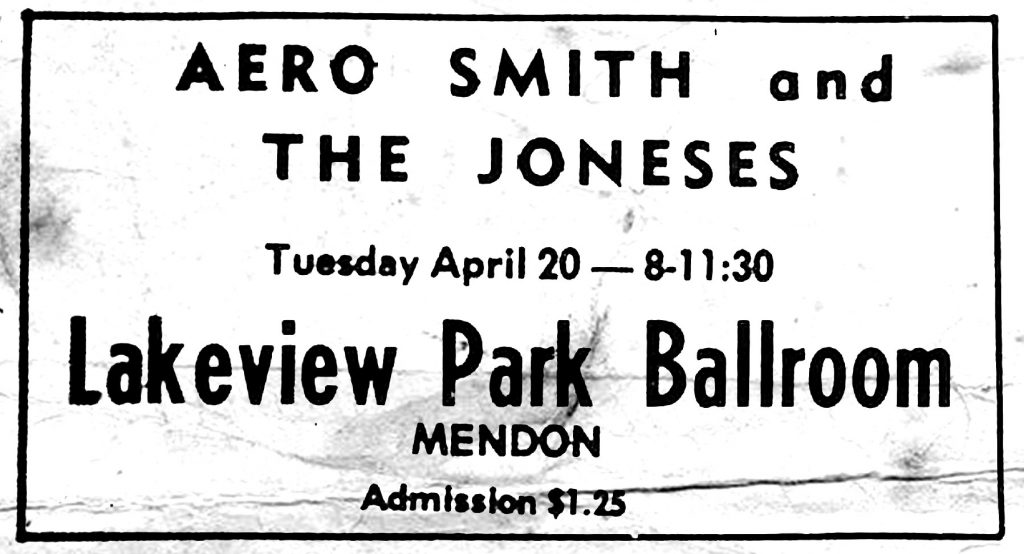

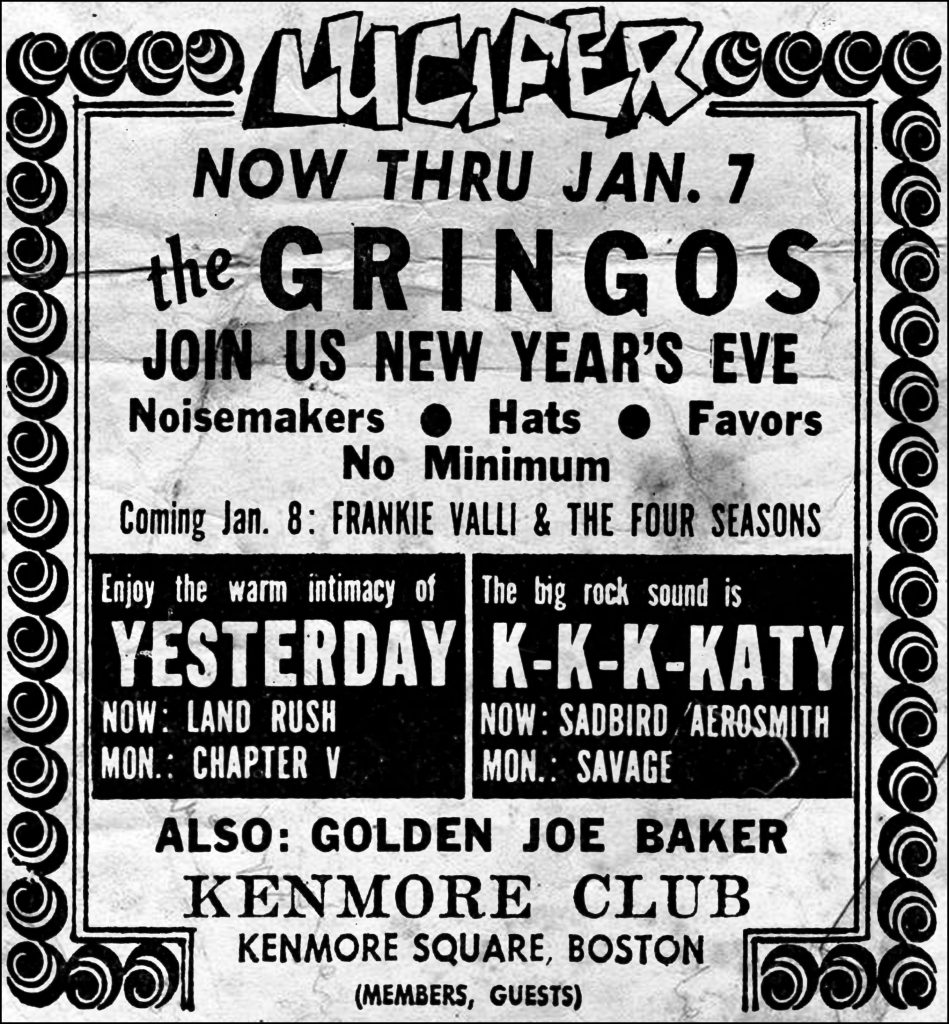

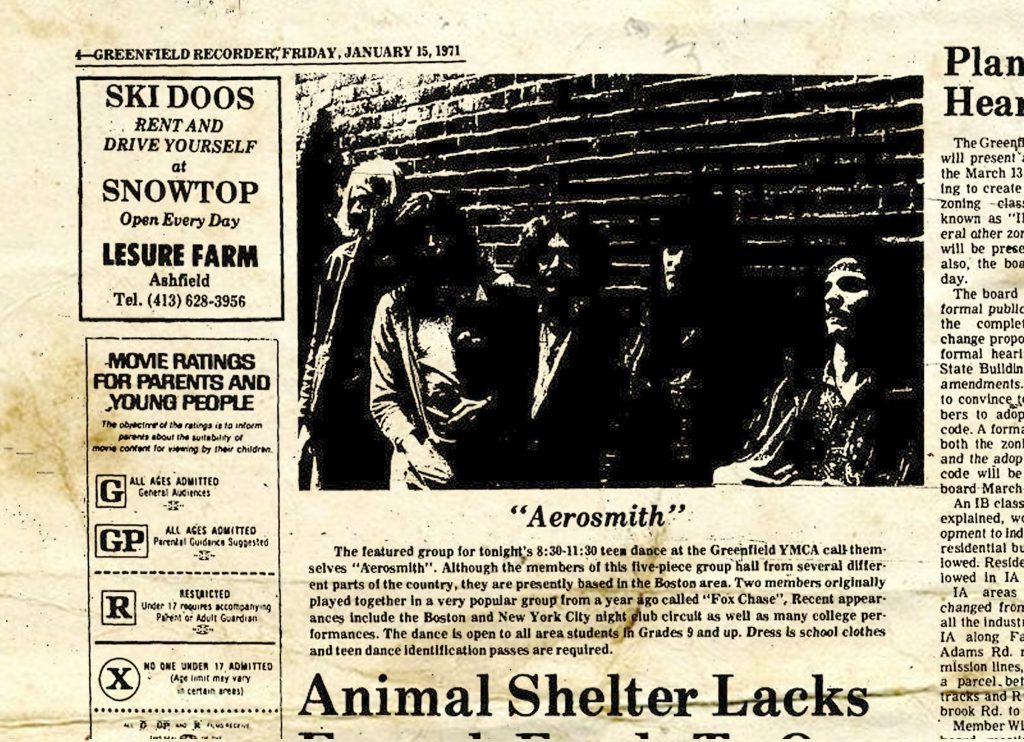

With a few weeks of rehearsals under their belt, Aerosmith played their first paying gig at the Nipmuc Regional High School’s gym in Mendon [Massachusetts] on November 6, 1970. Their set consisted mostly of covers), though six of the songs performed that night later turned up on Aerosmith albums. Steven and Joe had a big blow-up following the show with Joe being accused of playing too loud. It wasn’t the first argument on that topic, and it certainly wasn’t the last. For Tom [Hamilton, bassist], the band wanted to start out doing things their way: “We were not at all interested in going to clubs and playing five sets. So, we picked out songs that were fun for us to play and that people could dance to. We did frat parties and gigs like that. So, you first create and realize your stylistic identity by the songs that you pick to cover” (Guitar for the Practicing Musician, 5/1986).

Other shows in town hall auditoriums followed through the end of 1970. As 1971 dawned, the group broadened their horizons toward various regional venues they had played with other bands previously, often shows booked by Ed Malhoit. By April 1971, with just a handful of shows performed, the band was starting to look to recording demos to send in to record labels, but other than Steven, they were utter novices with few useful connections. They were very much a cottage industry, a band paying their dues slowly trying to work their way up. During the summer of 1971, the band started undergoing a crisis, caused by a deterioration with the band members’ relationship with [founding second guitarist] Raymond Tabano.

Playing with Raymond for a few months made it clear to Joe that it was not the sort of dual-guitar relationship he had been looking for. He recalled, “That’s one of the reasons I was so attracted to Fleetwood Mac and especially the Yardbirds when they had Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page in the band at the same time. They were breaking tradition with two lead guitar players in the same band. It wasn’t like listening to the Shadows or the Ventures where you had one guy playing lead and one guy playing chords. I didn’t have that with Ray, and I wanted that element in Aerosmith” (Ken Sharp/Rock Cellar Magazine, 11/7/2014). Furthermore, Raymond was strong-willed, independent and often combative.

Playing with Raymond for a few months made it clear to Joe that it was not the sort of dual-guitar relationship he had been looking for. He recalled, “That’s one of the reasons I was so attracted to Fleetwood Mac and especially the Yardbirds when they had Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page in the band at the same time. They were breaking tradition with two lead guitar players in the same band. It wasn’t like listening to the Shadows or the Ventures where you had one guy playing lead and one guy playing chords. I didn’t have that with Ray, and I wanted that element in Aerosmith” (Ken Sharp/Rock Cellar Magazine, 11/7/2014). Furthermore, Raymond was strong-willed, independent and often combative.

Listen to “Movin’ Out,” recorded in 1971

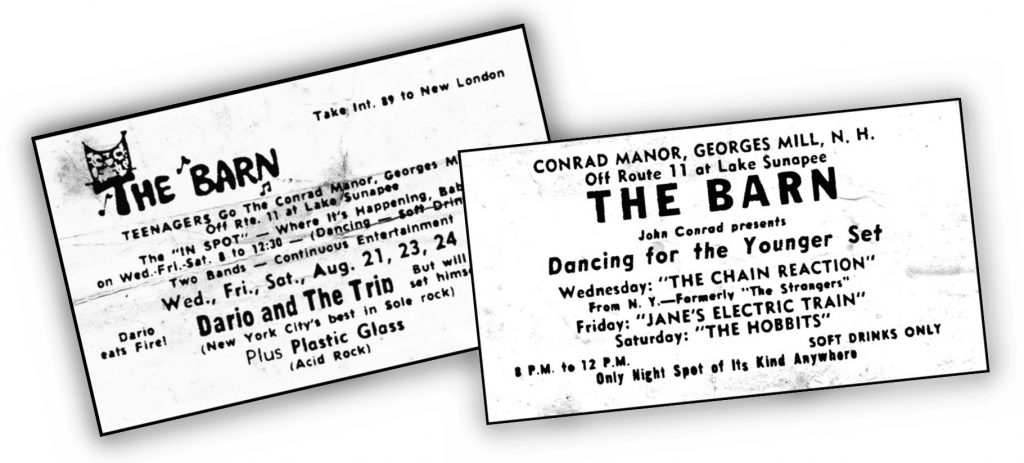

But for Joe, the most important issue was Raymond’s musical growth. Raymond was very much aware of his musical inadequacies and external distractions but was unapologetic. When the band returned to Sunapee [New Hampshire, where the band had an early home base] to play a show with Joe Jammer at The Barn in the summer of 1971, they attended a Justin Thyme show down the lake at Sunapee Harbor. From the moment Aerosmith encountered Brad Whitford, Raymond’s days were numbered, even though he attempted to force the other band members to choose him or Steven.

The site of the Savage Beast in Ascutney. Brad Whitford’s first show took place here. (Photo by Julian Gill, used with permission)

Raymond recalled his exit: “When Joe started going out with Elyssa Jerret and she met this guy, Joe Jammer. But he’s the one that put that thought into her head that, ‘You got to get somebody else, Ray’s not dedicated enough.’ It turns out that Twitty Farren, who used to play with me and Steven in William Proud, had a band in Salem, Mass., called Justin Thyme. It was him, Bobby Lidel, Jerry Belligue and Brad Whitford. So, Elyssa told Joe to check out Brad, and Joe decided he liked Brad’s playing better than mine and that I wasn’t dedicated enough. So, Tom told me, ‘We think that maybe you’ve got to practice more. We’re going to get another guitar.’ I didn’t really even give a shit at that point. So, Brad basically came from his band into Aerosmith, and I wound up in Justin Thyme. We even opened for them one time, in Revere, Mass., in 1972. I can’t remember the name of the place.” But he didn’t go meekly. Ultimately, it took Steven’s direct intervention, prior to a booking at the Savage Beast in Ascutney, Vermont, to make it clear to Raymond that he was out of the band.

Boston-born Brad Whitford started out on the piano and trumpet, neither of which lasted long. When his father bought a cheap acoustic guitar, Brad co-opted it, finding it more appealing. By his early teens, Brad was informally attached to his guitar, preferring to learn material himself, after taking some basic lessons locally. Sharing a room with his older brother, he was introduced to the songs of the day, and those songs were naturally the ones he’d learn to play along with. After high school, Brad studied at Berklee College of Music for a year while playing in another band, Stray Cat. He dropped out of Berklee, finding what he perceived as a snobbish attitude of the jazz crowd contrary to his rock outlook. And anyway, he wanted to focus on playing music full-time.

Brad recalled, “I felt that there was something telling me, ‘Hey, man, you should be playing, not studying.’ So, I left Berklee after a year because I thought I would learn a lot more out in front of people, playing my axe every night” (Circus Raves, 11/1975). He then joined Justin Thyme, which included Dwight “Twitty” Farren on lead, a band that Farren had put together following the demise of William Proud. During the summer of 1971, they had a gig scheduled at Lake Sunapee during the summer. Members of Aerosmith turned up to check out Farren’s new band, and Brad wowed them. He impressed them more the following night at The Barn when Joe Jammer jammed with Aerosmith and Perry left his guitar on stage. Brad picked it up and proceeded to rip it up with Jammer. A week after the hijinks at The Barn, Joe Perry called Brad to get a feel for his interest joining the fledgling Aerosmith. When Brad moved into 1325, living arrangements there were still cramped, but helped by Steven and Joey having moved to another nearby apartment.

Brad started rehearsing with the band, with Raymond still part of the scene, making his debut during a Labor Day residency at the Savage Beast. He recalled, “My first gig was at a little club in Vermont. The name of the club was the Savage Beast (laughs), and we were playing a rock ’n’ roll club show, so it wasn’t like a real high-pressure thing, and we’d been rehearsing like crazy. It felt good and it worked out really well. I think we knew we were on the right road” (Glide Magazine, 7/1/2014). Brad’s addition had little other than an impact on the music in the autumn of 1971, and they continued in much the same way as they had been. The band’s first major break came when they auditioned for George Paige, who was road-managing Edgar Winter at the time. After hearing them play he became a believer and agreed to help them, even though he thought the band’s internal tensions might quickly result in the band’s dissolution.

Related: Producer Jack Douglas talks about the Aerosmith years

Aerosmith recorded a demo of “One Way Street,” which was duly submitted for consideration to the label, not that they had much confidence with their performance of a song that was relatively new at the time. George duly took the tape to Stephen Paley, Epic’s A&R contact in New York City, and was flatly rejected. A second break around this time was Aerosmith’s debut in New York City, though it’s debatable whether it was much of a glorious homecoming for Steven. The band managed to land the opening slot at the Academy of Music on a bill headlined by Humble Pie, which would have pleased Brad, and Edgar Winter’s White Trash. With the show not being in a school cafeteria or local club, it was, essentially, their professional industry debut.

Following another taste of the big time, the band limped back to Boston and returned to the school cafeterias where they’d been performing. It was a rude awakening to the vagaries of broken equipment, but also an indication that they needed proper guidance and organization to progress. Sometimes, the gods are fickle—what is given with one hand is taken away with the other. A series of misfortunes followed the band during the winter of 1971-72, some of which were unnecessarily self-inflicted. A steady stream of bookings at the Officers’ Club at the Charlestown Navy Yard were cancelled after an incident of petty theft. Not only did the band lose a decent payday, but the side benefit of a hearty roast dinner thrown in, would have made a nice break from the monotony of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches or brown rice that formed the staple of their diets.

Following another taste of the big time, the band limped back to Boston and returned to the school cafeterias where they’d been performing. It was a rude awakening to the vagaries of broken equipment, but also an indication that they needed proper guidance and organization to progress. Sometimes, the gods are fickle—what is given with one hand is taken away with the other. A series of misfortunes followed the band during the winter of 1971-72, some of which were unnecessarily self-inflicted. A steady stream of bookings at the Officers’ Club at the Charlestown Navy Yard were cancelled after an incident of petty theft. Not only did the band lose a decent payday, but the side benefit of a hearty roast dinner thrown in, would have made a nice break from the monotony of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches or brown rice that formed the staple of their diets.

Then came the departure of their original roadie, Mark Lehman, which should hardly have been surprising with the later admissions of how poorly they had treated him. Once his van had been superseded by the group’s purchase of a school bus, his days may well have been numbered anyway. Regardless, his importance to the band from their very conception can’t be minimized. He made their first 14 months of existence much easier than it might otherwise have been, performing much of the thankless heavy lifting and lugging equipment and bodies that made their gigs possible. When he left, they still had the bus, but not the road manager/roadie with the experience required, even at a basic level. Gary Cabozzi filled in for the interim, to lug the band out to a gig at Marlborough High School, halfway between Boston and Worcester. But they also lost their rehearsal space at Boston University. And, to add to their woe, the band members still living at 1325 Commonwealth received their first eviction notice. It was a bleak period where the challenges facing the young band were mounting.

Searching for a new place to rehearse, the band was advised to check out the Fenway Music Theater by a connection to the facility’s assistant manager. There, at a time morale was at a low, Aerosmith was introduced to John O’Toole. After trying to get them to pay for the privilege of rehearsing there, he allowed them a few days free—in case he liked them. The Fenway had been closed for much of 1971 but had reopened for a single show during the summer (June 30, for Frank Zappa the Mothers with Gross National Productions for two sold-out shows). It then reopened on a more regular basis on December 17. In between bookings, the owners planned to showcase and audition unknown acts on Sundays. A February 1972 date had originally been booked for a T-Rex show, with that band having embarked on their first major U.S. concert tour. However, ticket sales were so poor that the show was canceled, and the theater’s manager asked Aerosmith, who’d been rehearsing there, to perform the date for what audience turned up.

Searching for a new place to rehearse, the band was advised to check out the Fenway Music Theater by a connection to the facility’s assistant manager. There, at a time morale was at a low, Aerosmith was introduced to John O’Toole. After trying to get them to pay for the privilege of rehearsing there, he allowed them a few days free—in case he liked them. The Fenway had been closed for much of 1971 but had reopened for a single show during the summer (June 30, for Frank Zappa the Mothers with Gross National Productions for two sold-out shows). It then reopened on a more regular basis on December 17. In between bookings, the owners planned to showcase and audition unknown acts on Sundays. A February 1972 date had originally been booked for a T-Rex show, with that band having embarked on their first major U.S. concert tour. However, ticket sales were so poor that the show was canceled, and the theater’s manager asked Aerosmith, who’d been rehearsing there, to perform the date for what audience turned up.

After the positive audience response, an impromptu audition followed. Hamilton continues: “The next day John said, ‘There’s a manager here to see you.’ We couldn’t see him, the lone figure in this big theater, but we said to ourselves, ‘OK, start playing, he’s out there.’ So, we played for about half an hour, the lights went off, the curtain closed, and he was gone, but he left behind a management contract. It was pretty exciting—that was really a scene out of some movie! So, he started to manage us” (Shark Magazine, 8/24/1989). The “he” was one Francis “Frank” Connelly.

After the positive audience response, an impromptu audition followed. Hamilton continues: “The next day John said, ‘There’s a manager here to see you.’ We couldn’t see him, the lone figure in this big theater, but we said to ourselves, ‘OK, start playing, he’s out there.’ So, we played for about half an hour, the lights went off, the curtain closed, and he was gone, but he left behind a management contract. It was pretty exciting—that was really a scene out of some movie! So, he started to manage us” (Shark Magazine, 8/24/1989). The “he” was one Francis “Frank” Connelly.

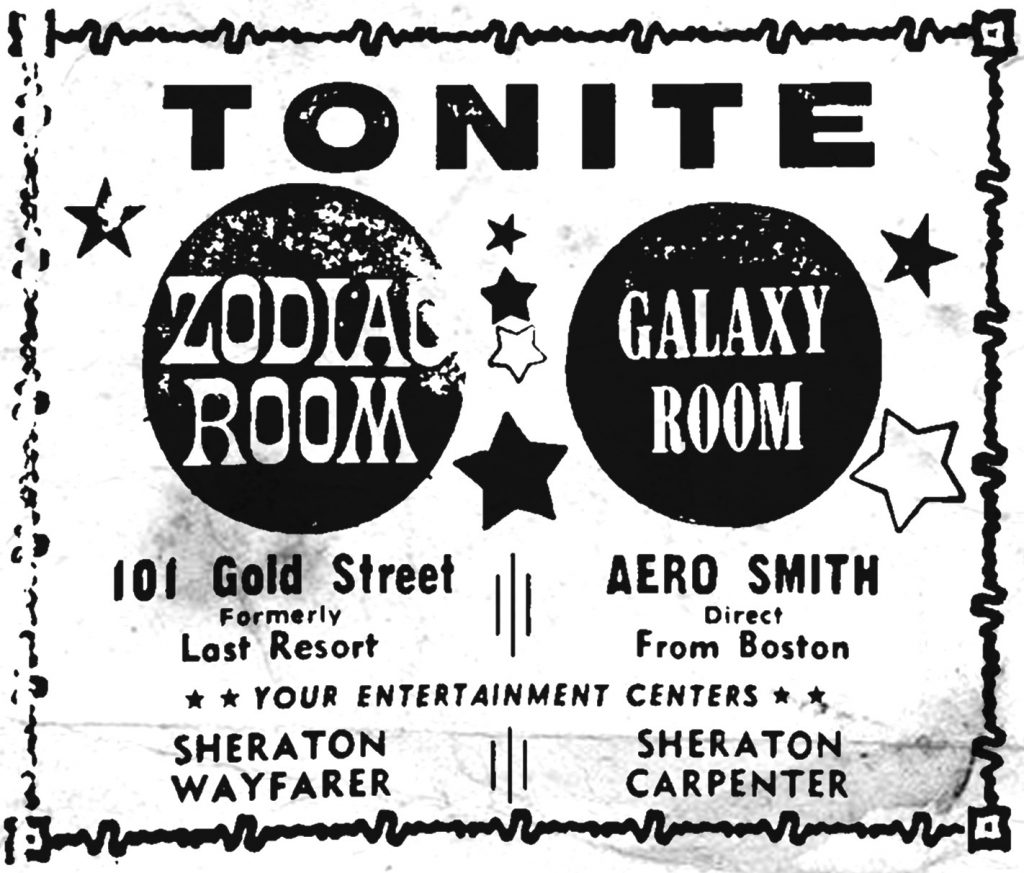

As Perry recalled, the timing couldn’t have been more perfect: “We took the contracts back to our apartment, and we sat down at the kitchen table with the contracts in one hand and the eviction notice in the other. We just looked at each other and shook our heads in disbelief. That’s how close it was.” Frank then installed them at engagements at various hotels to tighten up their performance through a grueling series of nightly sets. As he told Steven at the time, the multiple sets nightly weren’t for his benefit, but for the benefit of the rest of the band. They simply lacked the performance experience that Steven had already earned. It also reinforced that the club grind was not something they wanted to be doing. The band focused on their job—making music and writing and refining the arrangements of their original songs.

Following this period of woodshedding, the band returned to New York City to perform a showcase at Max’s Kansas City. There was no interest, though Aerosmith also opted not to enter the same glitter scene that New York Dolls were part of; performing at venues such as the Mercer Arts Center, Kenny’s Castaways and the Popcorn Pub. In mid-1972, Aerosmith still wasn’t much welcome outside of New England, and, shockingly, they only played their first billed non-BU show in Boston on May 20 (filling in at the Fenway on Feb. 26 doesn’t quite count).

Connelly, who drove the band to gigs in his car once their bus finally died, also obtained rehearsal space for the band at Boston Garden. They were using that space when the Rolling Stones returned for a pair of shows, July 18-19, 1972. He also had the band rehearse at Caesar’s Monticello in Framingham, Mass. Managing a band in Boston was one thing, getting them a national record deal was an entirely different proposition, and Frank knew his limitations. Part of his skill was knowing the right people, and he was already close with Steve Leber. Leber had been the head of the William Morris Agency music division but had broken off to partner with David Krebs. They formed Leber-Krebs in early 1972. Leber-Krebs was interested in Aerosmith and made them their second signing (Record World, 12/13/1975). After further woodshedding by the band, Leber-Krebs set up a showcase for Columbia Records’ Clive Davis and Atlantic’s Ahmet Ertegun at Max’s. Ertegun wasn’t overly impressed with Steven’s very obvious parallels with Mick Jagger, and regardless, Atlantic was already the distributor for Rolling Stones Records (via Atco) and had a solid rock band roster.

Listen to an outtake of “On the Road Again” from 1972

Most importantly, he felt that Aerosmith wasn’t quite ready for a record deal and needed another year of development. That was a blow to the band in one sense, Atlantic was the rock label powerhouse of the time, while Columbia was better known for softer acts such as Barbra Streisand, Simon & Garfunkel, and Chicago. Ultimately it didn’t matter, Davis was more than impressed with them. With Aerosmith, Columbia had a hard rock act that would present new challenges.

Related: Aerosmith will return to the stage in 2022

- Aerosmith’s Early Years: 1970–72—Book Excerpt - 03/26/2022

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationAerosmith, America’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band. I’ve seen them multiple times, even with Jimmy Crespo in the line up when Joe Perry and Brad Whitford left the Band.To this day, that is still one of my favorite Aerosmith albums, “Rock In A Hard Place.”