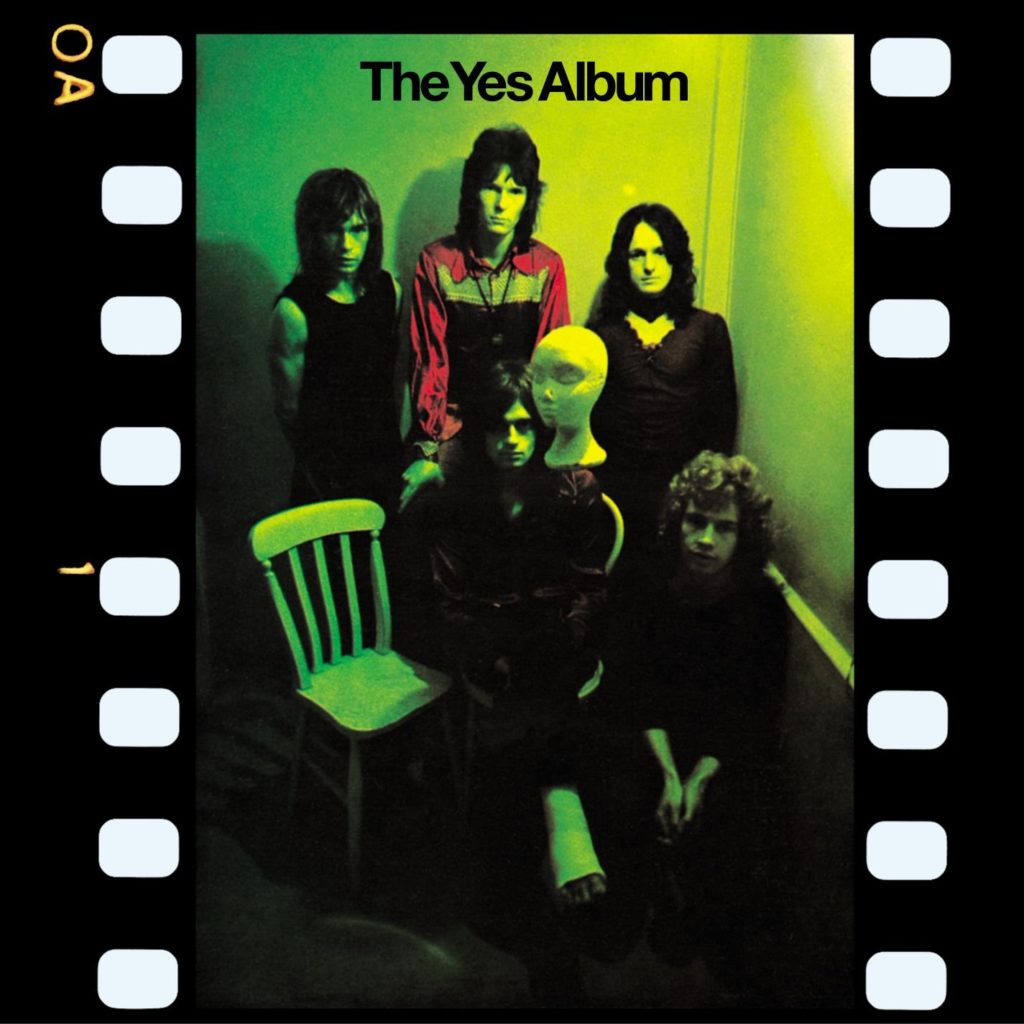

After two musically solid but poor-selling albums, the five-piece psychedelic-progressive rock group Yes privately suspected their label Atlantic was looking for some serious commercial progress in order to justify keeping them under contract. Their London-based A&R man Phil Carson was typically hands-off, but with label-mates like Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Led Zeppelin and CSNY catching fire, Yes could easily be left behind. In late spring 1970 they retired to a farm in Devon, England, for rehearsals with a “make or break” attitude.

After two musically solid but poor-selling albums, the five-piece psychedelic-progressive rock group Yes privately suspected their label Atlantic was looking for some serious commercial progress in order to justify keeping them under contract. Their London-based A&R man Phil Carson was typically hands-off, but with label-mates like Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Led Zeppelin and CSNY catching fire, Yes could easily be left behind. In late spring 1970 they retired to a farm in Devon, England, for rehearsals with a “make or break” attitude.

The band had been used to building LPs from a combination of their own compositions and a sprinkling of unusual cover tunes, often radically reworked from their sources (the Byrds’ “I See You,” the Beatles’ “Every Little Thing,” Buffalo Springfield’s “Everydays” and Richie Havens’ “No Opportunity Necessary, No Experience Needed” had appeared on the Yes and Time and a Word albums). This was to be their first album of entirely original material.

Vocalist Jon Anderson (who initially spelled his first name John), drummer Bill Bruford, keyboardist Tony Kaye and bass player Chris Squire were integrating their new guitarist Steve Howe, after original member Peter Banks left in April. Howe, who’d previously been with the “freakbeat” band Tomorrow, was at home in a number of genres, including folk, blues and country, and was soon exerting a strong influence on the group sound as they wrote and rehearsed new material. His main axe was the Gibson semi-acoustic ES-175, often considered a jazz guitar. He was the type of versatile player who could take advantage of it. He could play powerful block chords, wail jagged solo lines, flat-pick or fingerpick; whatever it took, he supplied it.

Bruford was likewise able to be subtle one minute and crash the next. Using a jazz approach, he tended to imply the main beat rather than always state it as a rock drummer would. His approach was defined by variety. Squire played bass like a lead instrument, generally with a heavy-gauge pick. Like the Who’s John Entwistle, he sounded at times like a low-pitched guitarist rather than a harmonic accompanist, part of the rhythm section. Kaye had trained as a concert pianist, but he’d abandoned classical music for pop, playing a Vox Continental in various groups before joining Yes in 1968 and settling on the Hammond B-3 organ as his main squeeze.

Anderson sang in a high tenor, and was responsible for most of the group’s lyrics, which tended toward the mystical, pastoral and mythological. Yes’ producer-engineer Eddy Offord described how the group teased Anderson for his wordplay: “The band gave him such a hard time. They’d all say to him, ‘John, your f**king lyrics don’t make any sense at all! What is this river/mountain stuff?’” Offord says Anderson would always explain, “I use words as colors, for the sounds of the words, not the actual meaning.”

Related: Our interview with Jon Anderson on Yes’ early years

Working at Advision Studios in London during autumn 1970, the group aimed for precision and even perfection. Most of the time Squire and Bruford recorded their parts and all other instruments and vocals were meticulously stacked on top, filling the 16 tracks available. Recording their complex, multi-part songs sometimes in takes as short as 30 seconds, they redesigned and edited pieces together as they went. Some heavily rehearsed sections were wedded to spontaneous studio creations. Offord was so expert that for much of the time the listener can’t hear the seams. So what appears to be superhuman effort, with musicians switching tempos, moods and effects at will, is actually a result of brilliant musicians who could hear the totality of the music in their heads as it emerged in bits, and a producer who could make it sound organic even when it was built like an assembly-line machine.

In an interview for yesworld.com, Offord recalled, “Bill Bruford didn’t like Jon messing with the tracks once they were recorded. I remember we were trying something—Jon wanted to have some echo in the background—and Bill got up and yelled, ‘Why don’t you put the whole f**king record in the background with echo then?’ But what I learned about working with them was, if somebody has an idea, it’s better to try it than sit around debating it.”

The nine-minute “Yours Is No Disgrace” kicks off the LP with a show of force, a sort of warped tango rhythm with Bruford and Howe assertively locked in, extremely prominent bass work, a Howe transitional solo and Kaye’s organ holding the strands together. Anderson and harmony vocals don’t enter until 1:30, with a tempo change, a Hammond B-3 bed and lyrics that are both evocative and opaque: “Yesterday a morning came, a smile upon your face/Caesar’s palace, morning glory, silly human race.”

Instrumental effects and changes in dynamics and tempo continue to oscillate, circling back like a classical sonata to theme and variations. There are sections that sound like prime King Crimson or Genesis; the arrangement keeps us guessing. At the 6:00 mark, Howe performs a dazzling series of solos in different styles, but isn’t allowed to linger before Anderson re-enters. At this point the lyrics are even wilder: “Battleships confide in me and tell me where you are/Shining flying, purple wolfhound, show me where you are.”

Strangely, the next track is “Clap,” a Chet Atkins-style acoustic guitar piece recorded at Howe’s very first live gig with Yes, at the London Lyceum on July 17, 1970. Incorrectly and unfortunately listed as “The Clap” on the original LP, it’s a fine showcase for Howe, but what it’s doing sequenced between “Yours Is No Disgrace” and another nine-minute epic, “Starship Trooper,” is a mystery. Surely such a contrast would have worked better tucked somewhere on side two? Howe laid down a longer version of “Clap” at Advision, but it wasn’t released until 2003 when Rhino issued an expanded CD of the album.

“Starship Trooper” is in three parts running together, with “Life Seeker” written by Anderson, “Disillusion” by Squire and Howe’s “Würm.” Anderson’s at his peak, and again the instrumentalists are constantly impressive and in motion.

Listen to Bruford’s variations as he moves around the kit and Squire puts in spectacular punctuation. At one point, Howe’s guitar track is run through a flanger, giving it a synthetic sound. He also does another Atkins-like country backing for a multi-tracked vocal grouping. Howe’s final section is a solid rocker that pounds a couple of chords into submission, Kaye dominating the background and Howe up front.

Related: Remembering Chris Squire

Side two begins with a two-parter meshing Anderson’s “Your Move” and Squire’s “All Good People.” The first half, with lyrics that use a game of chess as a metaphor for relationships, was released as a single and did get some AM airplay, but the FM dial took to the whole thing and made it ubiquitous, helping The Yes Album on its slow but steady trek to gold record status when released on February 19, 1971. It’s one of Yes’ most melodic and even fun tracks, all the while quoting multiple John Lennon lyrics, and Anderson turns out to be right about the shape of the words being more important than the literal meaning.

“Your Move” utilizes a drum-bass tape loop, which was Offord’s solution to a frustrating session in which Bruford and Squire labored hard but couldn’t get it right for long enough. Listen for Howe’s overdubbed 12-string. Squire’s bouncy “All Good People” is about as jaunty as Yes ever got, and it’s remained a fan favorite for 50 years.

“A Venture,” written by Anderson, fades in on Kaye’s delicate piano, Howe chimes in and the track becomes a very Beatlesque upbeat romp. On an extended version, released in 2014 as part of a deluxe CD/Blu-ray reissue supervised and remixed by Steve Wilson, there’s nearly two minutes of extra soloing, Howe and Bruford doing some excellent work. Offord has said he regrets the early fade on the original LP.

The album concludes with the strong “Perpetual Change.” It’s got a very cinematic, dramatic opening, after which Howe does a brief countrified electric solo, and the tumult dies out for Anderson’s gentle entry. The choppy main theme re-enters (listen what Bruford does here), and then, true to the title, it switches back into a lower gear. Much of the track consists of two overdubbed Yes bands playing in different time signatures.

The Yes Album was very successful, and Yes was at last well-established as one of rock’s perennial stadium-filling acts. It would be Kaye’s last album with the group (until he returned to the lineup more than a decade later). They wanted him to integrate synthesizers and other electronic sounds into the mix, and he wasn’t having it. His replacement, Rick Wakeman, was more than amenable, and Yes’ next discs, Fragile and Close To The Edge, were even bigger hits. The behemoth Tales From Topographic Oceans, which partisans cite as the apotheosis of ’70s prog-rock, was waiting in the wings.

Watch Yes perform “Yours is No Disgrace” live in 1971

A 2023 Super Deluxe Edition, along with many other expanded editions of Yes classics, is available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and the U.K. here.

9 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI saw Yes perform this album in summer 71 as the opening band for Jethro Tull. I had never heard of them but went out and bought the album the next day and played for as many people as I could.

Well I saw the same concert 1971 Wildwood convention center New Jersey where the best concerts I’ve ever seen in my life yes I went out bought that album too

After being a Yes fan for 40+ years, it is the Yes Album that I have come to realize is the most appreciated by me. It simply is timeless, and I find new things to appreciate about it every time I listen to it. It is Yes in top sonic form, condensed down to it’s very core of talent and purity.

Thank you my friend and congratulations on such an excellently written, finely detailed article. I will surely revisit this album with your deep insights will make it more interesting and enjoyable.

Never forget hearing this for the first time. It struck me as sounding bright, tight, positive and uplifting. The very essence of the word yes. I always thought wow this music needs to have Mellotron. Obviously the band thought so too. Goodbye Tony Kaye. Hello Rick Wakeman. Yes!!!

Loved them all and have seen many line-up changes over the years and just sad as many groups, the infighting and egos get in the way, with separate groups playing until recent! Don’tcha ya just hate it when talent like this, lays waste because they can’t get along and their induction so long overdue by the biased Hall is insane, but nice they were inducted too by fellow progressives from the Great White North..Geddy and Alex! I see the colors in Jon’s words too and maybe sometimes the others couldn’t see them, but they felt them! If you haven’t ever heard Wakeman’s Journey to the Center of the Earth it’s an amazing album and can’t recommend the trip enough! One of their shows supporting the 90125 album tour I believe in 84 at Forest Hills stands out as a memorable performance with Trevor Rabin they played Gimme some Lovin’ Spencer Davis classic to close out the show, very cool and awesome show! Would hope Steve and Jon could bring it together for some final shows, though unfortunately not likely with Chris and Alan gone now!!

It was nice to get 5.1 mixes of some Yes albums a few years ago. Vinyl just couldn’t contain everything going on, and the bass would sometimes overwhelm the rest.

Thank you, Mark, for your excellent research. It was a pleasure to read you. On my side, the first time I heard Yes was on an AM station playing Your Move during the summer of 1971. Good song! so I bought the single (the format I loved at the time). Weeks later, I saw the LP at my favorite record store and noticed on the back cover that Your Move was 3 minutes longer. As progressive music was inspiring me more and more (Procol Harum, Jethro Tull, King Crimson,…), I bought my first Yes’ album. I was so curious to hear the longer « hit » Your Move that I listened to the side 2 first. The music was so great that I have listened the side 2 again and again. Days later, I finally listened to side 1. Accidentally, this LP became for me this way to listen : side 2 first and side 1 after (so Clap was just at a good place) and Starship Trooper was really an incredible final song with its nearly 4 minutes of insistant rythmic that was remind me the final part of I Want You by The Fab Four 😉

Another band turned down by Apple Records and a good thing too . They would have gone the way of Jackie Lomax and Badfinger .