Talking Heads—‘More Songs About Buildings and Food’: Artful Music

by Mark Leviton Having put themselves on the map with their debut Talking Heads ’77 and its single “Psycho Killer,” Talking Heads were unafraid to inject an even higher level of spontaneity and playfulness into the sessions for their follow-up. If their first album sounded, in the words of The Village Voice’s Frank Rose, “like a well-orchestrated epileptic fit,” what might happen if the quartet invited the producer Brian Eno to oversee their next? “When you encounter something new in art, you get a feeling of being slightly dislocated,” Eno had said after encountering the punk and “no wave” scene in New York City, of which Talking Heads was a major part. “And with that are emotional overtones that are slightly menacing as well as alluring.”

Having put themselves on the map with their debut Talking Heads ’77 and its single “Psycho Killer,” Talking Heads were unafraid to inject an even higher level of spontaneity and playfulness into the sessions for their follow-up. If their first album sounded, in the words of The Village Voice’s Frank Rose, “like a well-orchestrated epileptic fit,” what might happen if the quartet invited the producer Brian Eno to oversee their next? “When you encounter something new in art, you get a feeling of being slightly dislocated,” Eno had said after encountering the punk and “no wave” scene in New York City, of which Talking Heads was a major part. “And with that are emotional overtones that are slightly menacing as well as alluring.”

For Talking Heads drummer Chris Frantz, Eno’s “special talents” meshed with their own. As he told Melody Maker’s Ian Birch at the time, “It seemed like every idea he had we thought was a good idea…He would be the first person to admit that he’s not a virtuoso in the sense that he plays a really boss guitar or mean piano…We were all completely open to the idea of him ‘treating’ the sound. He did it on almost every instrument, distorting or changing or intensifying sound.”

Working at Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas during March and April 1978 on the LP eventually dubbed More Songs About Buildings and Food, David Byrne (vocals, guitar, synthesized percussion), bassist (and Frantz’s wife) Tina Weymouth and ex-Modern Lovers multi-instrumentalist Jerry Harrison could take advantage of cheaper hourly rates, glorious weather and the Sony MCI mixing console Eno favored for his previous work with Devo, David Bowie and others. Basic tracks were reportedly completed in five days—mostly first or second takes—which allowed three weeks dedicated to experimenting, with a spontaneous, collaborative spirit fostered by Eno, who contributed his own instrumental and vocal parts here and there as the tracks were fleshed out. Weymouth praised how Eno and engineer Rhett Davies miked the room and their instruments, and says, “We left all the mistakes in and were just as happy with the result.”

Talking Heads’ aesthetics were highly influenced by the world of modern art (Franz, Weymouth and Byrne had all attended the Rhode Island School of Design, although Byrne didn’t graduate). Musically, they ignored borders and genre limitations: Frantz once told Rolling Stone, “The big difference between us and punk groups is that we like K.C. and the Sunshine Band and Funkadelic/Parliament,” and Harrison insisted to journalist Joe Nick Patoski, “We don’t fit into anyone else’s category, so we’re going to have to create our own.”

Related: Our Album Rewind of the band’s next release, Fear of Music

As to the tunes, in 2003 main writer Byrne looked back on the first Talking Heads albums in his liner notes to the Once In A Lifetime boxed set, writing, “The songs have a disturbing emotional resonance that I probably didn’t appreciate at the time. They are, it now seems to me, the work of a fairly disturbed mind—my own—that was using this writing and performance to find out how to be in the world…The bizarre syntax and skewed outlook that produced these songs are unrepeatable…a gift from a stranger, and that stranger is me.”

Released on July 14, 1978, More Songs About Buildings and Food made it as high as #29 on the national Billboard album chart, and their version of Al Green’s “Take Me To the River,” the only non-original on the set, became the group’s second unlikely pop single hit.

“Thank You for Sending Me An Angel” leads off the album with a galloping beat and a relentlessly circular set of lyrics, delivered in a hiccupping style by Byrne, wholly committed to lyrics that don’t easily yield meaning: “You can look, you’ll walk circles around me/But first, I’ll walk in circles ’round you/But first, I’ll walk around the world.” At just a bit over two minutes, it ends abruptly before you can catch your breath. The mutant funk of “With Our Love” follows, one of several songs that depend on Weymouth’s fluid bass, overlapping staccato or chiming guitar lines, tempo shifts and Byrne’s alternation between gulping, yelping and shouting lyrics that are both assertively aggressive and tongue-in-cheek: “Forgot the trouble, that’s the trouble/With our love.”

“The Good Thing” has a hint of John Lennon’s “Hold On” in the opening melody, until a ragged multi-voice choir billed as “Tina and the Typing Pool” comes in to handle the deadpan words, pitched somewhere between a term paper and haiku: “A straight line exists between me and the good thing/I have found the line and its direction is known to me/Absolute trust keeps me going in the right direction/Any intrusion is met with a heart full of the good thing.” Byrne told Birch the song was “written as a reaction to dealing with the music business. I felt the music business is essentially amoral.” (Good luck finding that sentiment in the lyrics.) The last minute or so sounds like an affectionate parody of James Brown and the J.B.’s, with Byrne exhorting everyone to “Work! Work!”

The Byrne-Frantz co-write “Warning Sign,” according to Byrne, is “the most decadent song. I get images of naked people and drugs and people being sick from taking too many drugs. It’s just a lot of images of depraved behavior.” Frantz and Weymouth lead, with a mid-tempo intro that’s almost cinematic. Byrne’s voice is heavily treated as he declaims typically opaque lyrics (“Warning sign/Look at my hair, I like the design/It’s the truth”), but it’s the variety of guitar sounds and rhythms—choppy, pretty, scratchy—that are the buried treasures here.

“The Girls Want to Be With the Girls” is a happy, poppy confection, and features a swirling synthesizer line and tinkling piano for extra color. It contains some of the DNA of “Psychotic Reaction,“ “96 Tears,” “1-2-3 Red Light” and other AM radio one-hit-wonders the group would sprinkle into its earliest sets at the Mudd Club and CBGB. To close the side, “Found a Job” explodes as a kind of twin to the opening “Thank You for Sending Me An Angel.” The pushy chorus is among Byrne’s strongest: “Judy’s in the bedroom, inventing situations/Bob is on the street today, scouting up locations/They’ve enlisted all their family/They’ve enlisted all their friends.” The whole band is locked into the infectious dance groove; K.C. and the Sunshine Band would be proud.

The lovely, chiming theme of “Artists Only” weaves a spell for 30 seconds as side two of the original LP begins, until Byrne shouts “Let’s go!” and it morphs into a passionate, quirky, altogether enthralling performance, perhaps the best of the LP. Its off-the-wall humor (words by Byrne and his RISD friend Wayne Zieve) is spot on, skewering the sensitive artiste who won’t show you his piece—or his song?—until it’s finished. The track seems to emerge in real time like an audio action painting, as the protagonist announces, “I’m painting, I’m painting again.” That might have been followed by “I’m cleaning my brushes” but Byrne goes for “I’m cleaning my brain” instead. He yelps, “I don’t have to prove that I am creative!” twice before admitting, “All my pictures are confused.”

The tinny guitar intro of “I’m Not in Love” is quickly followed by a track full of stop-start tempo changes, mood alterations, the driving 4/4 of Frantz and Weymouth and exclamations from Byrne in half a dozen different voices. At three minutes in, the track turns into a full rave, with plenty of timbre-swapping effects courtesy of Eno. The momentum continues with the brilliant “Stay Hungry,” a Franz-Byrne co-creation with a title copped from a muscle magazine (no doubt inspired by the 1972 novel of that title about body-builders). According to Franz, the song’s “tying together the feeling of being a hard-working artist with trying to be a handsome young man at the same time.” The opening African rhythm looks forward to Talking Heads’ Fear of Music and Remain In Light albums, before the tempo throttles down, and we get a series of sections that keep the listener guessing, the repetitious chorus (“Move a muscle, move a muscle, move a muscle/Make a motion, make a motion, make a motion”) delightfully off-kilter.

“Take Me To the River” is next, unabashed “white soul” with a terrific drum, bass and organ sound, and a Byrne vocal performance that goes from restrained to unleashed as the moment dictates. “We had been performing it and people liked it live,” Byrne said, explaining its inclusion to Ian Birch, admitting it might be “the least expected genre for us to pick. Those Al Green songs are really weird, though—mixing Jesus with sex and stuff.” Green had written it with his guitarist Mabon Hodges and cut it for the 1974 album Al Green Explores Your Mind. The Talking Heads version went Top 40 when released as a single and has been a radio and streaming favorite ever since.

The album’s longest cut, at 5:30, “The Big Country” is one of Byrne’s most ambitious compositions, and concludes the LP. He wanted to make the verses “as objective as possible, just by straight recording what you see from an airplane, and then the choruses I guess you’d call more subjective. They were pretty irrational and it got a little mixed up toward the end. I thought it would be interesting to present something very objectively and then throw in this irrational hatred of it and not give any reason why.” Hence, a chorus that insists, “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me/I couldn’t live like that, no siree!” The slide guitar gives it a light “country” feel, and the soaring melody is some of the first evidence that film scoring might be in Byrne’s future. There’s some real weight when he sings, “I’m tired of travelling, I want to be somewhere.”

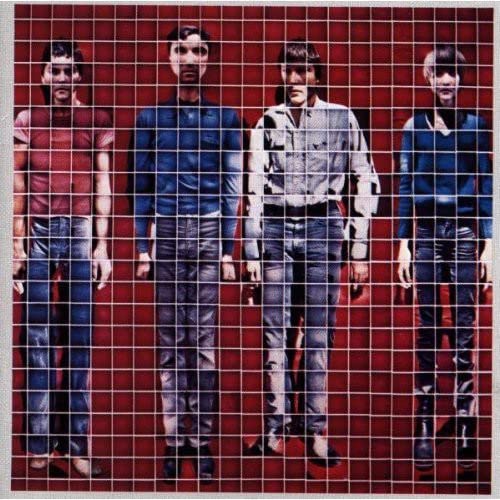

The striking front cover of More Songs About Buildings and Food, conceived by Byrne and executed by artist Jimmy de Sana, comprises 529 close-up Polaroid photographs of the group. The rear cover features “Portrait U.S.A.,” a photomosaic image of the country as seen from space, built from more than 500 photos taken by the Landsat satellite. Such impressive visual elements and design carried over to the lighting and costuming for Talking Heads shows, eventually culminating in their celebrated Jonathan Demme-directed Stop Making Sense film in 1984.

Around the time of the release of More Songs About Buildings and Food, David Byrne was asked if in some sense what he was doing with Talking Heads was more art than music. He replied, “I’m sure it’s music. However, I’m not sure it’s rock and roll. Rock and roll is a dead issue. What’s interesting to me is what function we do perform for people…I’m not sure yet.”

The album is getting a Super Deluxe Edition on July 25, 2025. It’s available for pre-order in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. A 4-LP vinyl version is available for pre-order in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Other Heads’ classics are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Related: The band paid tribute to Sire Records co-founder, Seymour Stein, who died on April 2, 2023

2 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThis was a big improvement over the first Talking Heads album. Although most of the material originated along with the songs on ’77 (Artists Only was their traditional opening song when they played as a trio at CBGB), it was produced much better; the first album didn’t do justice to their sound.

“Found a Job” anticipated the YouTube revolution of two decades later (“Inventing situations, putting them on T.V.”).

The version of “Stay Hungry” here is a truncated edition (with a coda added) of the original song they used to perform live. I haven’t been able to locate any recording of the original version, which was longer and held together much better as a song. The only record I have of it is a badly made cassette taping of one of their CBGB concerts (spoiled by a malfunctioning erase head).

Byrne’s comments about his emotional state confirm what I feel about the group: their output falls into 3 phases – the first being the acutely original songwriting up through “Fear of Music”, which I consider their finest achievement; then there was the period where they made songs out of single-chord jams, which still resulted in some classics; then the third period where they returned to conventional songwriting but somehow the songs from that period never struck a chord with me the same way that the older ones did.

My close friend, who worked at the local Tower Records, brought MSABand F over one day and said we had to hear it. The first listen completely threw me. I didn’t know what to think of this crazy sound and band. Soon, it was the only music our small group could listen to. Nothing else was comparable or satisfying during that summer of ’78. I still listen to it often and it still sounds fresh.