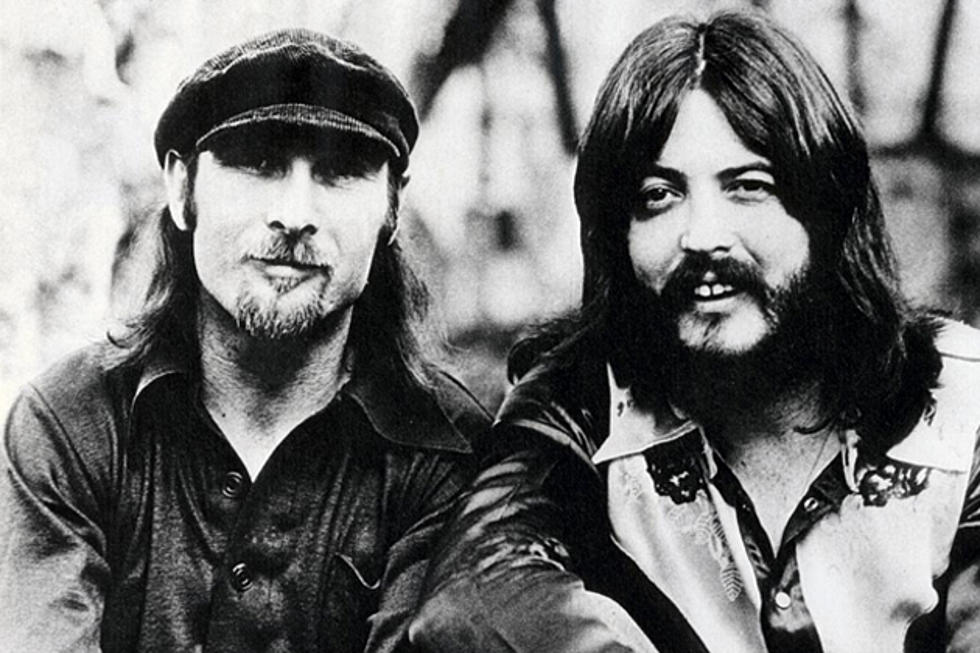

You could easily sum up their career in less than 50 words: Seals and Crofts were a soft-rock duo that scored three big hits in the 1970s: “Summer Breeze,” “Diamond Girl” and “Get Closer.” They disbanded in 1980 to devote more time to the Baháʼí faith.

But there is, not surprisingly, more to the story, both leading up to and following Seals and Crofts’ relatively brief moment in the sun.

Like so many other pop-rock tales, theirs begins in Texas.

James Eugene Seals, known as Jim, was born in the small Central Texas town of Sidney, on October 17, 1942 (some reports say 1941), while Darrell George “Dash” Crofts, from nearby Cisco, preceded him by roughly three years. The two musically inclined teens met in 1958 as members of Dean Beard and the Crew Cats, a rockabilly band led by the same-named singer/pianist dubbed the West Texas Wild Man.

The same year that Seals and Crofts joined his band, Beard was asked to join the Champs, the Los Angeles group that was just coming off a national #1 instrumental smash, “Tequila.” Not having anything better to do, the two friends headed west with Beard and also got the gig with the Champs, with Seals on tenor saxophone and Crofts playing drums. By 1959 Beard had departed the Champs but Seals and Crofts stayed with them, also adding vocal backups, billed as the Chimes. In addition, they began recording their own singles, at least one time billed as the Trophies.

Just as things were really kicking in for the group, Crofts, born August 14, 1938, was called up by Uncle Sam, who required his service in defending his country; he spent most of his time in the military until 1964, when he rejoined the Champs full-time. During those years, there would be several other charting singles for the group, none coming close to that first classic, but the Champs had enough work to keep them employed into the mid-’60s. Seals was also able to polish his songwriting chops, contributing a number of his own compositions to the band’s repertoire. He also spent a bit of time touring with rockabilly great Eddie Cochran (who died soon after) and wrote a tune recorded by country-pop hitmaker Brenda Lee. For a while, both Seals and Crofts also backed Glen Campbell, as part of the group the singer called the GC’s.

Listen to the Champs’ single “Mr. Cool,” featuring Jim Seals on tenor saxophone, Dash Crofts on drums and Glen Campbell on guitar

By 1965, it had become obvious to the two old friends that they were in a position to head out on their own and, besides, the Champs were fading quickly as the new British bands took over the rock scene. Seals had cut four singles for Challenge Records, and he opted to leave the group that year, although Crofts stayed on long enough for a Japanese tour. Upon his return, they both concentrated on session work and songwriting, lending their talents to the likes of Rick Nelson, Buck Owens and Gene Vincent. (Seals also reportedly contributed sax parts to More of the Monkees, the made-for-TV band’s second LP.)

Sometime in the early ’60s, Seals and Crofts also joined a band called the Dawnbreakers, and during that time they were introduced to the Baháʼí Faith, a century-old religion with roots in the Middle East. Baháʼí would become central not only to the lives of both artists but to their music: many of their songs were written around ideas espoused by Baháʼí scriptures, and Seals and Crofts, even at the height of their fame, never failed to talk about it and spread its principles every chance they got.

The most prolific and high-profile phase of the Texans’ career began in 1969, when the two musicians decided to team up as a duo that they would simply call Seals and Crofts. With Seals playing guitar, saxophone and violin, and Crofts on guitar and mandolin—both sharing vocals and harmonizing pristinely—they began crafting music that fit snugly into the still-emerging soft-rock and singer-songwriter modes.

It wasn’t easy at first. Their self-titled 1970 debut album failed to chart at all in the United States; the followup, Down Home, later that same year, squeaked in at #122. Even a gig at the famed Fillmore East, opening for England’s Procol Harum in 1970, failed to ignite their career as a stand-alone act. The third album—and first for the Warner Bros. label, titled Year of Sunday—fared even worse than the one before it, peaking at #133 in early 1972.

They were determined though, and in 1972, Seals and Crofts finally caught their break. One of their self-penned tunes, “Summer Breeze,” was released at the perfect time, August 1972, and found its audience readily. The single climbed all the way to #6 in America, and boosted the album of the same name to #7 in Billboard’s LP chart. Nearly a decade and a half since they’d joined the Champs, Jim Seals and Dash Crofts were finally tasting success.

“Hummingbird,” the song that opened the Summer Breeze album, reached #20 in early 1973, but by that time the duo was already at work on their next album. It, too, took its name from a hit single: “Diamond Girl,” its authorship again credited to both Seals and Crofts, became their second top 10 hit, peaking at the same position as “Summer Breeze,” #6.

Related: The biggest hits of 1973

The Diamond Girl album jumped to #4, outpolling the earlier collection—it would become the biggest seller of their career, establishing Seals and Crofts permanently as fixtures on soft-rock radio. Another single from the album, “We May Never Pass This Way (Again),” climbed to #21 and fans waited to see what the pair—now one of the hottest acts in the business—would come up with next.

What they came up with was a single—and album of the same name—that looked to Seals and Crofts’ faith for its inspiration and ultimately caused a severe blow to their popularity. “Unborn Child,” a song co-written by Seals and Lana Bogan, the wife of the duo’s recording engineer Joseph Bogan, was unabashedly anti-abortion in its lyrical stance. Released in early 1974, just a year after the landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision that ruled in favor of a woman’s right to choose the procedure, “Unborn Child” alienated a sizable segment of Seals and Crofts’ audience. Warner Bros. begged the duo not to release it, but Seals and Crofts ignored the warnings. While most of the pair’s more dedicated fans were aware of Seals and Crofts’ adherence to the Baháʼí Faith, many thought they’d gone too far in bringing their religion so unambiguously into their music. The single stalled at #66, although there were enough other songs on the Unborn Child album to elevate it to #14.

They had undeniably taken a hit commercially—“King of Nothing,” the followup single, from the same album, topped out at #60, and as the middle of the ’70s came into focus, it remained to be seen just how Seals and Crofts would fit in. (Ironically, the year 1974 also saw Seals and Crofts playing perhaps their biggest-ever gig, but one of the strangest: California Jam, a festival date that put them in the company of Black Sabbath, the Eagles, Deep Purple and others wielding considerably more volume.)

I’ll Play for You, their 1975 album, brought them back into the game, peaking at 30, with the title track finding its way to #18. But if there was any doubt in anyone’s mind, by 1976 it had evaporated. The single “Get Closer,” once again taken from an album of the same name, brought Seals and Crofts right back to that now-familiar #6 position—their third and final visit to that same spot. The album itself reached #37, their last to go gold.

For the most part, that was it for Seals and Crofts’ chart reign. There would be one last top 20 single, 1978’s “You’re the Love,” and an album, Takin’ It Easy, in 1978, that reached #78 (it even contained a disco-flavored tune). The Longest Road, released in 1980, didn’t even chart, and Warner Bros. dropped the duo.

With the music scene having shifted radically away from the sound they favored, Seals and Crofts decided to break up the act that same year, although they did occasionally continue to meet up for Baháʼí-related events. Crofts continued to play music in a country vein, while Seals took up coffee farming in Costa Rica.

(A trivia note: Dan Seals, Jim’s brother, was one-half of the duo England Dan and John Ford Coley, whose career path roughly coincided with that of Seals and Crofts. They actually scored four top 10 hits, most prominently “I’d Really Love to See You Tonight,” in 1976. Their last chart hit came in 1980. Dan Seals later enjoyed popularity as a country artist, and the two brothers even toured together—as Seals and Seals—but Dan died in 2009.)

Seals and Crofts reunited in 1991 for about a year and then again in 2004. They recorded a final album that year, titled Traces, but the audience for their kind of music had long ago moved on. Their recordings are available to order here.

Watch Seals and Crofts perform “Summer Breeze” live

9 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI remember a concert in the mid 70’s at the Hartford Civic Center – Michael Murphy opened for S&C, singing his one hit ‘Wildfire’.

Then, S&C put on a really good show. I still remember a ‘loud’ jam, where the sax figured prominently.

They put on a really good live show.

My Fair Share from the movie One On One was a big hit in late 70s.

After the concert they stayed and discussed their Bahai faith …

It’s a shame that their music, and many others as well, has to be qualified by how many “hit’s they continued to have. But it sounds like S&C, as well as many other recording artists who had a number of charting songs and albums picked up that mindset, about their own creativity and recordings, themselves, as so many disband when the huge sales wane. So I guess, at first, it’s about making music, and down the road it becomes about how much of it you sell. But I’m surprised that a musical pair such as S&C, who went ahead and put out such a controversial recording such as “Unborn Child,” against their record company’s, and everyone else’s, advice, because they believed in it, would simply throw in the towel when their record sales leveled off.

But as I was very familiar with the “Summer Breeze” album, I was simply amazed one day while driving along on a highway listening to the long version of “Hummingbird.” I know I’d heard that sound in the past countless times, but, somehow, it was like I was hearing it again for the first time. What I mean by that is that I was thrilled and astounded by the jazz-like innovative musical directions and amazing soaring harmonies that song took, especially toward the end of the song. Somehow, after all this time, and many vacant listens, I realized how astounding the song was. I’ve never quite looked at Seals & Crofts in the same light again.

Yes, Hummingbird is a song written in and for Heaven! It’s truly and purely beautiful! When mandolin takes over at the end!! Genius!

The dip-shit hat always weirded me out.

Back in the mid-seventies I was on a flight from Seattle to Memphis. I was assigned a seat next to Seals for the long flight. He seemed a pretty down to earth guy. Only thing is I thought he was Crofts. Turned out Crofts was on the flight too but several aisles up.

my parents told me their songs were completely relevant for that time and they will always be no matter what time!! when i need a calming time..i listen to them..the music today..too disruptive and disturbing…

My favorite and what I consider to be there most technical was Gabriel Go on Home