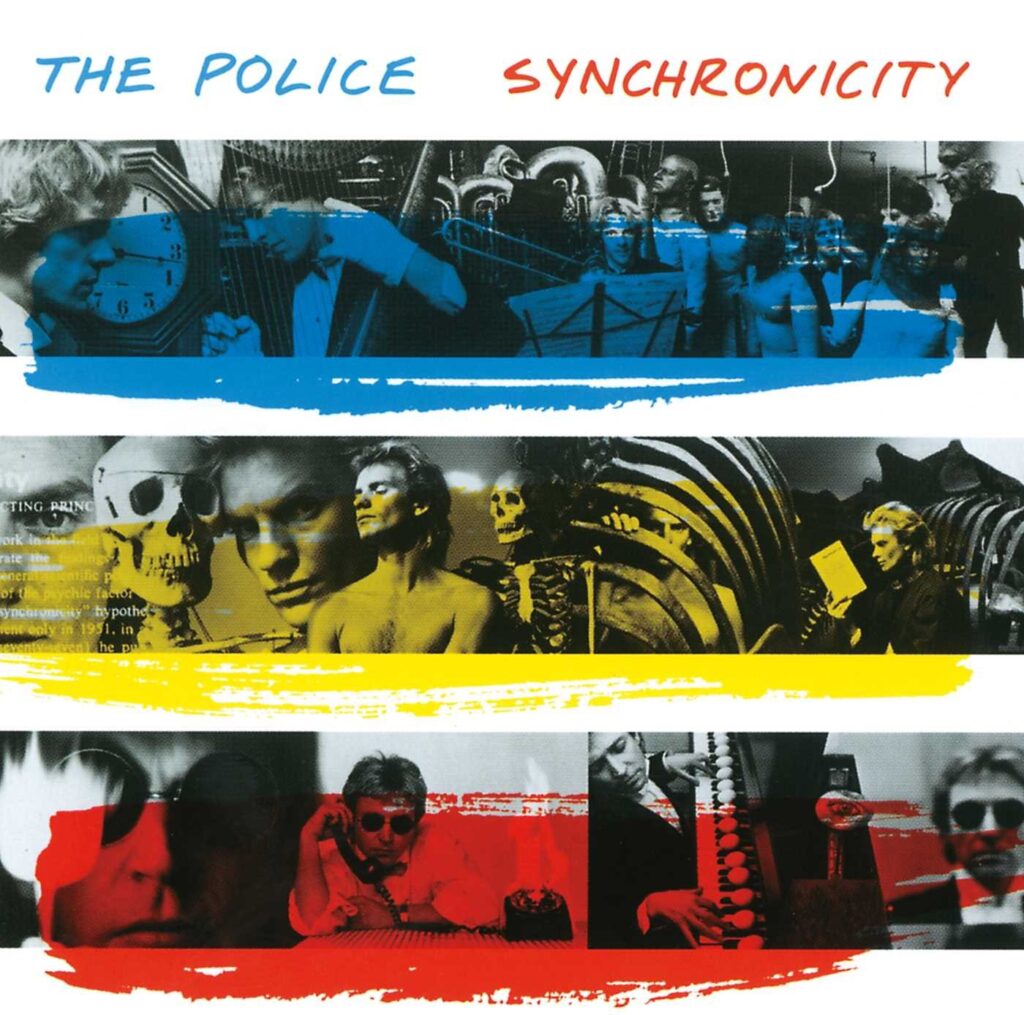

A Look Back at the Final—And Most Successful—Police LP, ‘Synchronicity’

by Amy McGrath The Police’s Synchronicity, released on June 17, 1983, marked a significant shift in the band’s sound, blending elements of rock, new wave and world music. Yet no one could have forecast that this album would be the finale to a trio that was distinctly at the top of unquestionable worldwide domination.

The Police’s Synchronicity, released on June 17, 1983, marked a significant shift in the band’s sound, blending elements of rock, new wave and world music. Yet no one could have forecast that this album would be the finale to a trio that was distinctly at the top of unquestionable worldwide domination.

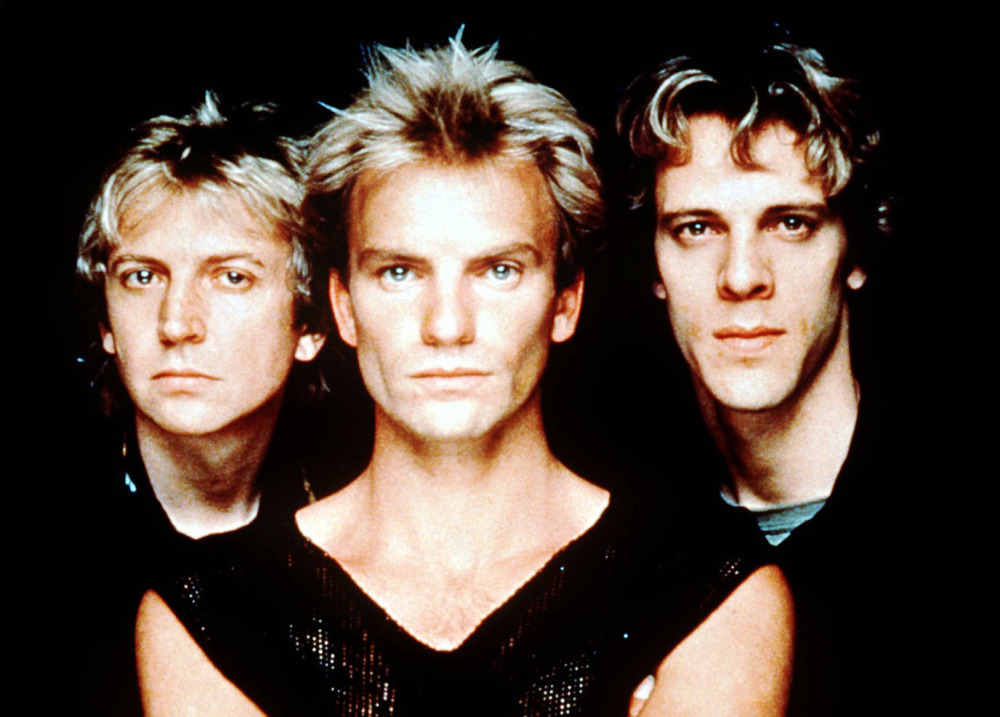

Having come off the success of 1981’s Ghost in the Machine, The Police—Sting, Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland—had been on a recording hiatus while touring the world, including the memorable 1982 Labor Day weekend headline appearance at the US Festival in San Bernardino, California. Copeland later termed this performance one of the band’s best ever and given the accolades since, it wasn’t hard to argue with that sentiment.

The secret sauce contained within Ghost in the Machine hinged on a number of elements, chief among them producer Hugh Padgham. Having made a name for himself with Phil Collins (Padgham created the monumental gated drum sound for the latter’s 1981 Face Value), he was brought back into the trio’s circle in December 1982 at AIR Studios in Montserrat, West Indies.

Significant overall was the dampening of the reggae influence heard on their previous releases. Padgham was herding the band away from their punkish ska minimalism and amplifying the trendy new wave synth melodies that were blazing hot and fast across the music industry: acts as far-ranging as Culture Club, Thomas Dolby, Duran Duran and Naked Eyes were already chart-grabbing just before the release of Synchronicity. But all of that would pale by year’s end in comparison to the Police.

With not a hint of irony, the lead-off track “Synchronicity I” takes no prisoners, with a skippy, bell-like synth twang and Copeland’s masterful syncopated cymbal ride that jumps to Sting’s hyperventilating rush of words, explaining what “synchronicity” is. Aside from Carl Jung’s definition (described as “events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection”), it’s a powerful intro. The further-released concert video ratcheted up the intensity, courtesy of directors Godley and Creme, and Copeland later remarked with humor, “It was a real ‘rama-lama’ way of starting our set on tour, though it almost killed me to start with that kind of onslaught every night.”

“Walking in Your Footsteps” has a swampy jungle backbeat from an OB-X synthesizer, courtesy of Sting finding a default program on the machine and composing the song the morning of the recording. Lyrically, the song addresses the extinction of dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period (“Fifty million years ago/You walked upon the planet so”) as the droning melody plays off smatterings of Summers’ screechy guitar.

A prominent footnote for the album’s third track, “O My God,” is the connection to Sting’s first band. Formed in 1974, Last Exit was the catalyst that brought Summers and then Copeland into Sting’s orbit during several years of crossing paths on the U.K. gig circuit. “O My God” had been performed as a Last Exit song with a dreamy, soft jazz undertone and Sting riding along with a hushed vocal. The 1983 version was transformed into a more Police-style offering, with a suspicious melodic helping of their 1979 song “Walking on the Moon.”

Summers’ offering of “Mother” occupies a curious slot, not only within Synchronicity, but in the Police canon. Generally regarded as the worst song on the album, with Summers’ manic discordant recitations over a barrelhouse rhythmic tempo, one wonders how this song ended up getting recorded in the first place. At the time, Rolling Stone found the screed “corrosively funny,” but unless one is a true devotee, best to jump the needle.

On the upside, the writing credit for Copeland’s “Miss Gradenko” benefits in large part to letting Sting handle the lead vocal. The subject matter has been speculated down through the decades as a storyline about Cold War espionage and the narrator’s concern for a female Russian spy’s safety. The rendering is no doubt fueled by the drummer’s family background—his father was a founder of the CIA—and it’s saved only by Sting’s confident treatment and less by Copeland’s repetitive lyrics.

Side one closes with “Synchronicity II,” which, for better or worse, is the apocalyptic cousin to the opening track. While Copeland has claimed in interviews that he put Sting “up against a wall” trying to wrangle any sort of meaning, one can surmise, as Sting has done in interviews, that it’s merely a connected element. However, there was nothing left to the imagination in the accompanying music video: the band, surrounded by scaffolding, performs in a windy, dystopian environment as Summers play-acted with the experimental Gittler guitar, Copeland hammered away on the kit and Sting lip-synced with his most zonked-out “Sting” look, all courtesy again of Godley & Creme.

Side two opens with the band’s first single, released ahead of the album, on May 20, 1983. What can be said 40-plus years on about the #1, eight-week chart topper “Every Breath You Take” that hasn’t already been critiqued, analyzed and/or celebrated? Largely overlooked by the public at the time in the brilliantly voiced delivery from Sting, is the portrait of a narrator of questionable character as he literally stalks a spurned partner. It’s almost a certainty how the song would be received in today’s cultural landscape, but in 1983, Sting was in the middle of a painful divorce and trying to find his emotional footing, although he publicly acknowledged the creepy and sinister overtones projected in the tune. However, the defining characteristics within the composition—Summers with his Robert Fripp-inspired plucking note riff in particular—meshed with Copeland’s understated percussive accompaniment, have made this song an undeniable classic.

The album’s third single, released in August, “King of Pain” (which topped out at #3 on Billboard’s Hot 100) is another bead in the string of connectivity found on Synchronicity. To modern ears, it comes off sounding a little self-centered with a sprinkling of redundancy. Yet the striking images conjured by the lyrics (“There’s a blue whale beached by a springtime’s ebb/There’s a butterfly trapped in a spider’s web”) were grounded in Sting’s post-breakup of his first marriage. Not unironically, his then-girlfriend, now wife Trudie Styler, contributed to his frame of mind in the songwriting. When he pointed out some solar activity in the sky, Sting explained, “Trudie discreetly raised her eyes to the heavens. ‘There he goes again, the king of pain.’”

One month ahead of that single’s drop was “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” another in the line of Sting’s word-stuffing verses, with mentions of Greek mythology (“Caught between the Scylla and Charybdis”) and,, according to Sting “bits of Doctor Faustus and the Sorcerer’s Apprentice thrown into the pot for good measure.” Its dark and foreboding tone, strung together with Copeland’s drum brush couplets and buzzy bottom drones, was put to good use in the accompanying video. Presented in slow motion (once more courtesy of Godley & Creme), the band is surrounded by corridors and altars of burning candlesticks, with an overacting Sting bopping throughout. Half pretentious, half relatable, the single charted on Billboard’s Hot 100 at #8.

The album’s final track, “Tea in the Sahara,” is a direct lift from the Paul Bowles book The Sheltering Sky. The character Port told a story in which three sisters are joined for tea in the Sahara desert by a prince, who then leaves, assuring them he will come back. Which he never does. It’s the kind of song structure Sting would more fully explore once he left the Police, characterized in his 1985 solo debut The Dream of the Blue Turtles.

The CD and cassette versions of Synchronicity contained an additional track, “Murder by Numbers,” that came together as the trio was having dinner at the studio. Summers had summoned up a plunking jazz riff, Sting got excited and the three rushed into the studio to record a dark-humored tale on the art of killing, that did end up as the B-side to “Every Breath You Take.”

Related: The inside story of MTV’s disastrous Police contest

The statistics of the 1983 version of Synchronicity can fill volumes. The jacket artwork was released in the U.S. with 36 variants containing differentiating color stripes of yellow, blue and red, along with interchanging band images. The album was then pressed on audiophile vinyl that appears as a dark purple hue when backlit. It reached #1 on the U.S. Billboard 200 and U.K. Official Charts and the group was awarded three wins at the 26th Annual Grammy Awards. Synchronicity was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2009 and in 2023 it was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

[A 2024 release of a 6-CD Super Deluxe Edition of the album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. A 4-LP collection is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. A 2-CD set is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. There’s a picture disc as well: U.S. and U.K.]

Watch the Police perform “Every Breath You Take” live

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationI remember turning cable on in the morning (USA Network?) in the 1980s, and watching Kathy Smith and two other athletic women doing exercises on a rotating stage as “Synchronicity II” played.

Ohhhhh-Ohhhhh-Ohhhhh!