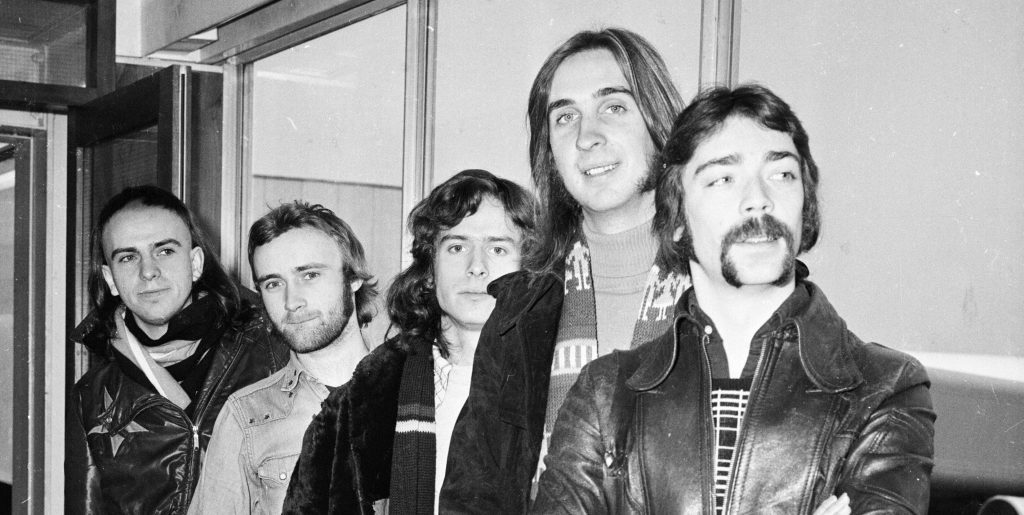

From the moment singer and composer Peter Gabriel began recording with Genesis, the band formed in 1967 with his friends at the posh English boarding school Charterhouse, it was clear his musical interests were only part of his wide-ranging curiosity. In his lyrics and onstage, he combined his study of history, science and philosophy with flamboyant visual and theatrical elements.

From the moment singer and composer Peter Gabriel began recording with Genesis, the band formed in 1967 with his friends at the posh English boarding school Charterhouse, it was clear his musical interests were only part of his wide-ranging curiosity. In his lyrics and onstage, he combined his study of history, science and philosophy with flamboyant visual and theatrical elements.

When this writer interviewed Gabriel in December 1973, during Genesis’ three-night run at the Roxy Theatre in Hollywood, he was staying with the band at the seedy Tropicana Motel, paying little attention to the rock and roll antics unfolding nearby on the Sunset Strip. He spent much of the interview talking about the science fiction novels and philosophy books he was reading while on tour, and how his onstage costumes (a geometric headdress, bat wings, a fox mask) helped the songs come to life. He was one of the most polite, intellectual rock frontmen in the business, but he did have a rather strange “reverse Mohawk” haircut, with a big notch of hair missing in front.

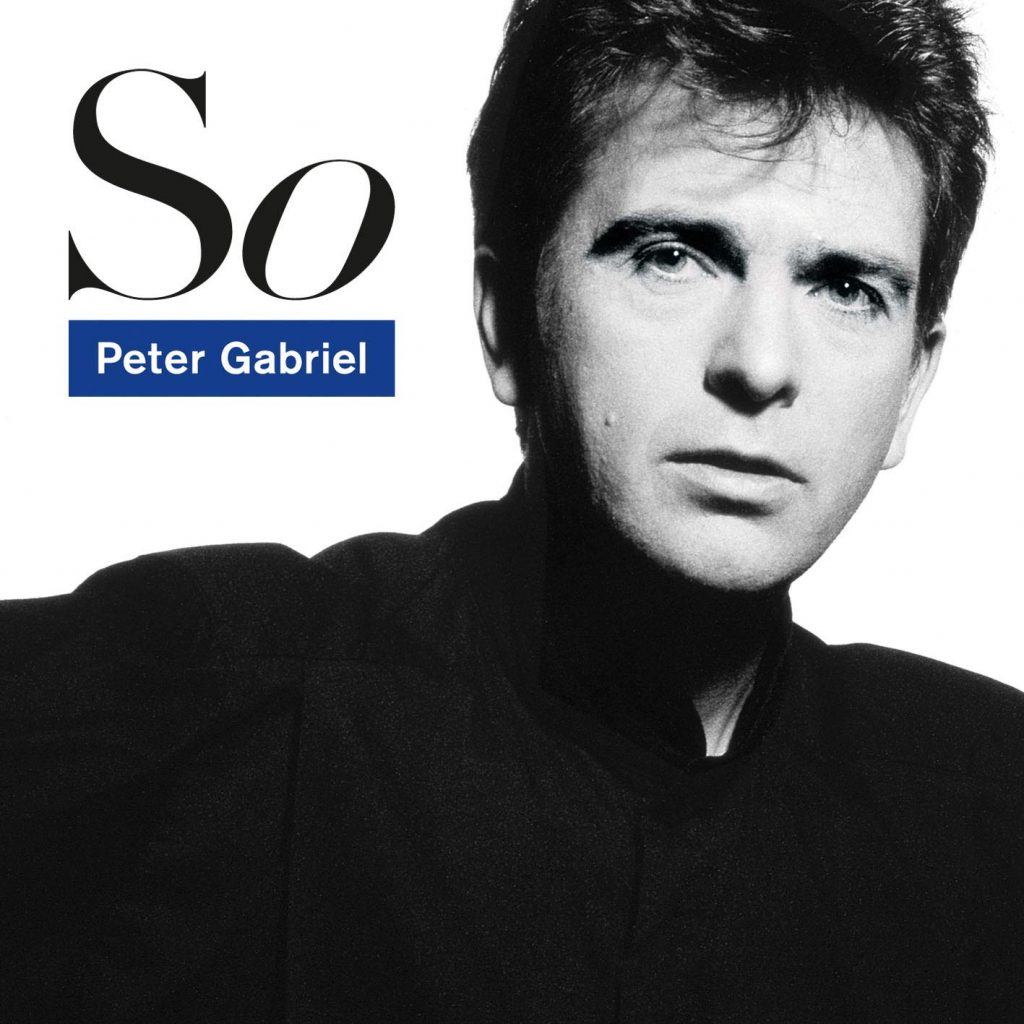

Through his time with Genesis, and his subsequent solo career, he continued to merge his intellectual pursuits into music that could be experimental, pop, R&B or whatever struck his fancy. After four well-received but commercially underperforming solo LPs, each titled Peter Gabriel, and the soundtrack to Alan Parker’s extraordinary 1984 film Birdy, Gabriel was looking for a co-producer who might shake him up in a good way. After considering Chic’s Nile Rodgers and the eclectic bass player Bill Laswell, he convinced his Birdy collaborator Daniel Lanois to continue staying with him, working in his well-appointed home studio, known as Ashcombe Studios, near Bath, England.

At the start of sessions, neither man could have anticipated they were about to produce an album that would not only bring unorthodox recording techniques, “art rock” and “world music” to the mainstream, but sell a zillion copies, yield the most-played video in the history of MTV, and make Gabriel an unlikely pop star. In a 2011 interview for Uncut, Gabriel said, “I’d had my fill of instrumental experimenting for a while, and I wanted to write proper pop songs, albeit on my own terms.” Lanois—no slouch when it comes to avant-garde ideas and the construction of subtle “ambient details”—helped Gabriel create a genre-bending masterpiece that didn’t require artistic compromises. And they had fun doing it.

The album that became So was recorded from February to December 1985. The proceedings started with guitarist David Rhodes, Lanois and Gabriel improvising on musical themes without lyrics (they called themselves “The Three Stooges”). Bassists Tony Levin and Larry Klein, pianist Richard Tee, violinist L. Shankar and percussionists Jerry Marotta and Stewart Copeland (of the Police) were among the many contributors who arrived in due course. Lanois added several guitar parts, and Gabriel played piano and, on nearly every track, the Fairlight CMI, Linn 9000 and Prophet synthesizers. Lanois engineered with Kevin Killen. The sessions in Bath (and subsequent overdubs at the Power Station in New York City) were lengthy, meticulous and far from cheap, even with time in a home studio being basically free: So reportedly cost upwards of $300,000. It was worth every penny.

The set begins with the powerful and mysterious “Red Rain,” with lyrics Gabriel says were based on a dream. The continual invocation, “Red rain is coming down/Red rain is pouring down,” suggests the color of blood is at the center of his vision. Gabriel and Lanois use several different “voices,” with echo, falsetto and a high “roughened” scream. The words may be simple (“I come to you defenses down/With the trust of a child”) but the effect is deeply ominous and disturbing.

The following “Sledgehammer” is nothing like “Red Rain.” It’s based on Gabriel’s love of American soul from the Atlantic and Stax labels, which he told Musician’s John Hutchinson “have been a pivotal influence on me… I was definitely trying to borrow the style of that period, and it is no coincidence that the man leading the brass section is Wayne Jackson, who is one of the Memphis Horns. I remember sneaking out from school [in 1967] to see them at the Ram Jam Club in Brixton. It was probably the best concert I’ve ever been to.”

At times the lyrics seem right out of the blues playbook (“Show me ’round your fruitcage/’Cause I will be your honey bee”), or a tongue-in-cheek way of referring to the very uncharacteristic funkiness on display (“This is the new stuff/I go dancing in, we go dancing in”). But given Gabriel’s literary bent, could the overall concept of a sledgehammer being “my testimony” refer obliquely to Franz Kafka’s famous dictum that “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us”? Drummer Manu Katché locks in perfectly with Tony Levin and David Rhodes, and the joyous background vocals from P.P. Arnold, Coral Gordon and Dee Lewis give Gabriel’s own authoritative singing a wonderful cushion. Released as a single, “Sledgehammer” went to #1 in Billboard, and the clever video directed by Stephen Johnson (with Claymation and stop-motion effects by Aardman Animations and the Quay Brothers) won a record nine MTV Video Music Awards.

Another of the album’s singles, “Don’t Give Up,” is powered by Gabriel’s discontent with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s economic policies. The narrator has hit hard times, unemployed and hopeless: “No fight left or so it seems/I am a man whose dreams have all deserted/I’ve changed my face/I’ve changed my name/But no one wants you when you lose.” His lover (played by Kate Bush after Dolly Parton turned down the gig) tenderly responds, “Don’t give up/’Cause you have friends/Don’t give up/You’re not beaten yet.”

“I started off on that song singing both parts myself, but I thought it would work better with a man and a woman singing, so I changed the lyrics around,” Gabriel told Hutchinson. “At one point I tried to work it up in a gospel/country style, and there are still echoes of that approach in Richard Tee’s piano-playing. The basic idea is that handling failure is one of the hardest things we have to learn to do.”

Few songs have the social impact of “Don’t Give Up.” Since release the song has transcended the story of its specific inception to achieve a universal impact, providing comfort to millions around the world. Gabriel’s ability to convey deep emotion is ever present in his work, whether political or personal.

The first side of the original LP concludes with “That Voice Again,” written as part of Gabriel’s preparation to score Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. Gabriel says he had the Byrds’ use of 12-string guitar in mind as he recorded the track, but it’s a long way from any jingle-jangle. L. Shankar’s violin is part of the dense background, while Manu Katché’s snare sound jumps out of the mix. There’s a stunning long-held note from Gabriel at the end of “Only love can make love.”

“In Your Eyes,” a gorgeous mid-tempo ballad released as a single from So, is another impressive outing for Katché, on various percussion instruments including talking drum. Senegalese vocalist Youssou N’Dour enters with wordless power at 4:39, joined by bass voice Ronnie Bright as the track fades. Michael Been from the Call and Simple Minds’ Jim Kerr are also part of the chorus. “In Your Eyes” is a romantic tour-de-force, with one of Gabriel’s most passionate vocals. In 1989’s hit film Say Anything, directed and written by former Rolling Stone journalist Cameron Crowe, Lloyd (John Cusack) holds up a boombox playing “In Your Eyes” to woo his love Diane (Ione Skye), a scene that’s become so iconic other rom-coms have parodied it. Lloyd doesn’t have to speak because Gabriel does it for him: “In your eyes/The light, the heat/In your eyes/I am complete.”

“Mercy Street,” with lyrics inspired by the poet Anne Sexton, is in the Brazilian “forro” rhythm. Gabriel had recorded the percussionist Djalma Correia in Rio de Janeiro, playing congas, triangle and surdu (a large bass drum). Improvising over the tracks at Ashcombe for a song called “Don’t Break the Rhythm,” Gabriel became dissatisfied with it, substituting an “English folk melody” he’d been toying with and importing the “Mercy Street” lyrics from yet another unfinished song.

In the 1986 Musician interview, he explained, “I tentatively added some great piano playing by Richard Tee, but that made the song too complex in terms of arrangement. There was a period when I was left on my own in the studio, and I started going at it again with the Fairlight. The percussion was put in then.” The track, which fades in slowly and delicately, features a near-whispered set of lead and harmony vocals, a “processed” sax from Mark Rivera, Larry Klein’s restrained, slinky bass and a whole stack of keyboards played by Gabriel. Credit to Lanois for helping design the remarkable atmosphere and background/foreground effects.

“Big Time” is another raver that might rightly be heard as a bit of a Talking Heads knock-off. It was almost as big a pop hit as “Sledgehammer” (it peaked at #8), with another droll MTV video starring Gabriel in a wacky-but-cuddly mood. Wayne Jackson’s horn section is back, as is the female vocal trio, and Tony Levin’s invention, the “drumstick bass,” drives the rhythm with plenty of help from Copeland’s drums, Simon Clark’s conventional and synthesized basses, and some very Chic-like guitars from Lanois and Rhodes.

“We Do What We’re Told (Milgrim’s 37)” refers to a famous psychology experiment that tests obedience to authority. Gabriel refers to the song as a “dark corner.” Minimal lyrics are quietly chanted, until at the very end, Gabriel erupts with a plaintive, yearning cry: “One doubt, one voice, one war, one truth, one dream.”

“Perhaps it’s the only track that rests on texture and atmosphere as its key elements. Most of the others are songs that you could strum along with on a guitar.” Jerry Marotta’s drums are meant to sound like “a heartbeat heard from the womb.”

“This Is The Picture (Excellent Birds)” appears only on the CD and cassette versions of So. It’s a co-write with Laurie Anderson, and was developed for a television project by the video artist Nam June Paik. “We were being pushed to combine forces, so we wrote and recorded the video and song in three days, which may be a record,” Gabriel told Hutchinson. “We quite liked the song, so we agreed that we could both use it on our separate albums. Hers [Mister Heartbreak] came out ahead of mine. The TV version is closer to Laurie’s recording; mine is based on the groove, while hers is more fragmented.”

Released May 19, 1986, So went multi-platinum as the big radio play and videos spread the word everywhere. Suddenly, Gabriel was competing commercially with Genesis and Phil Collins’ solo albums. At the 29th Annual Grammy Awards, So was nominated for Album of the Year, losing to Paul Simon’s Graceland, and “Sledgehammer” was up for Best Male Rock Vocal (Robert Palmer won), Record of the Year (Steve Winwood took it) and Song of the Year (lost to “That’s What Friends Are For”). Gabriel had never had such attention from the mainstream record business.

Gabriel’s live performances became a worldwide phenomenon, and he used his new clout to support human rights and various charities; he was part of the 20-date Human Rights Now! tour for Amnesty International in 1988. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2010 as a member of Genesis. and as a solo artist in 2014. Gabriel’s received numerous awards, including a Man of Peace recognition from Nobel Peace Prize laureates in 2006, the Polar Music Prize for songwriting, and an Ivor Novello Award for lifetime achievement.

In 2011, a partially re-recorded So was part of his orchestral project New Blood, and in 2012 a three-CD deluxe edition of So was released, with a fantastic 1987 Athens live show as the bonus discs. Gabriel continues to be a force as both musician and activist; he turned 75 on Feb. 13, 2025.

Watch Gabriel perform “Sledgehammer” live

Gabriel’s solo recordings, including his 2023 album, i/o, are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K here.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Gabriel’s final album with Genesis, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationGreat review of a truly groundbreaking bit of sustained brilliance. I had no idea Dolly had been asked to do the “Don’t Give Up” vocal. I have no doubt she would have given a great take on it, but Kate was the truly perfect choice. Have you heard Willie Nelson’s cover of it (with Sinead O’Connor) on his Across the Borderline LP? As is his wont, he owns it and makes it feel like an American lament. (Have youse guys ever reviewed that album? It’s a gem.) Thanks for your continued excellent journalism!