When the American literary institution Mad Magazine announced in the summer of 2019 that it was winding down publication after 67 years, commentators everywhere praised the publication for its biting satire and often absurdist, irreverent humor.

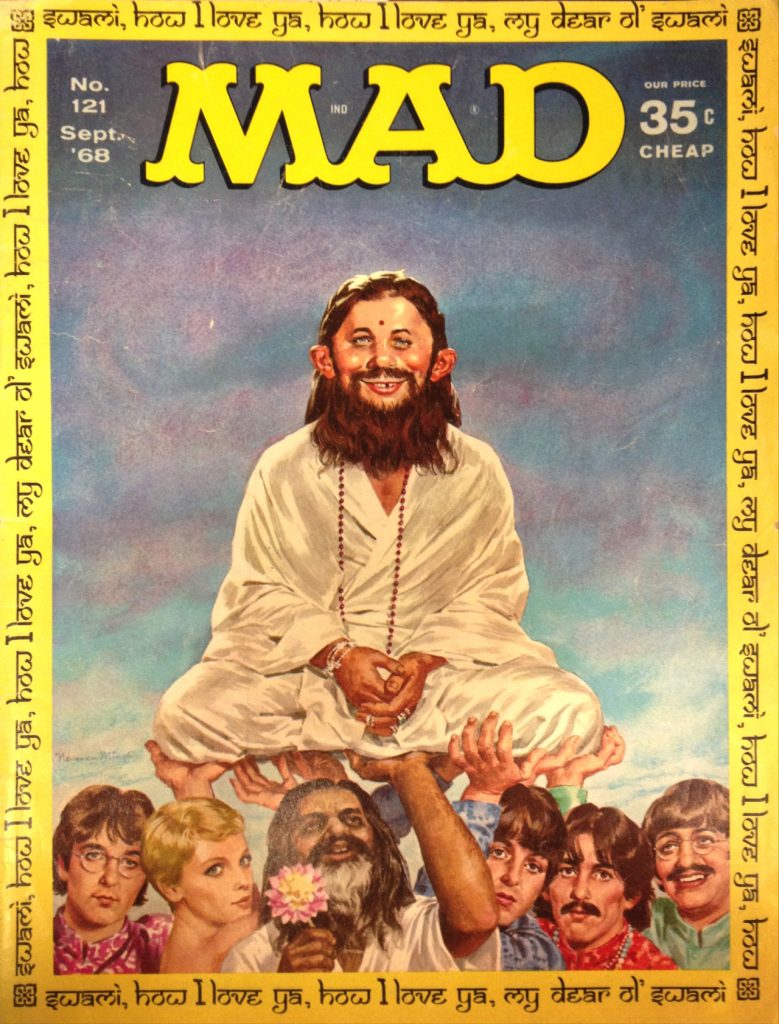

Known for its mascot, the gap-toothed, perpetual cover boy Alfred E. Neuman, and its “What, Me Worry?” slogan, the magazine was highly influential among the younger generations of readers during its heyday of the 1950s-’70s. What would a world without Mad be like?

Although publisher DC Comics confirmed rumors that the magazine would no longer publish new content or be sold on newsstands after its August 2019 issue (except for year-end reviews), instead recycling classic content, all seemed to agree that the end of Mad was truly the end of an era. Or was it? Its publisher is still churning out new issues every few months.

Mad, which called its staff of contributors “The usual gang of idiots,” was founded in 1952 as a comic book by editor Harvey Kurtzman and publisher William Gaines. (Its premiere issue had a cover date of October-November 1952 but actually arrived in August.) Under editor Al Feldstein, who took over from Kurtzman in 1956, by which time Mad had converted to the magazine format, it increased its circulation until it reached its 1974 peak of more than two million readers. Mad published more than 500 regular issues in all, as well as paperback books, reprinted special issues and more. It also spawned spinoffs and a popular TV program.

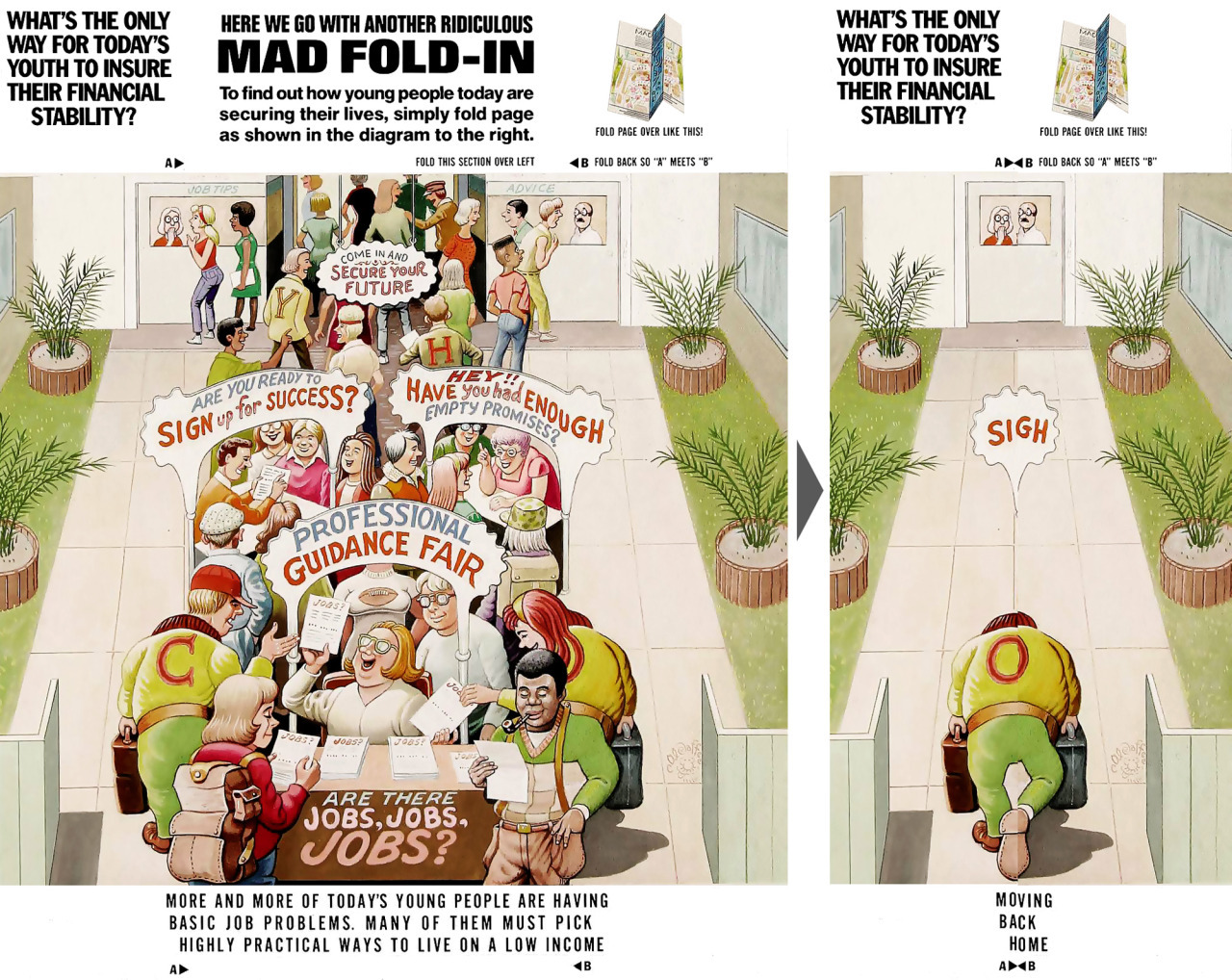

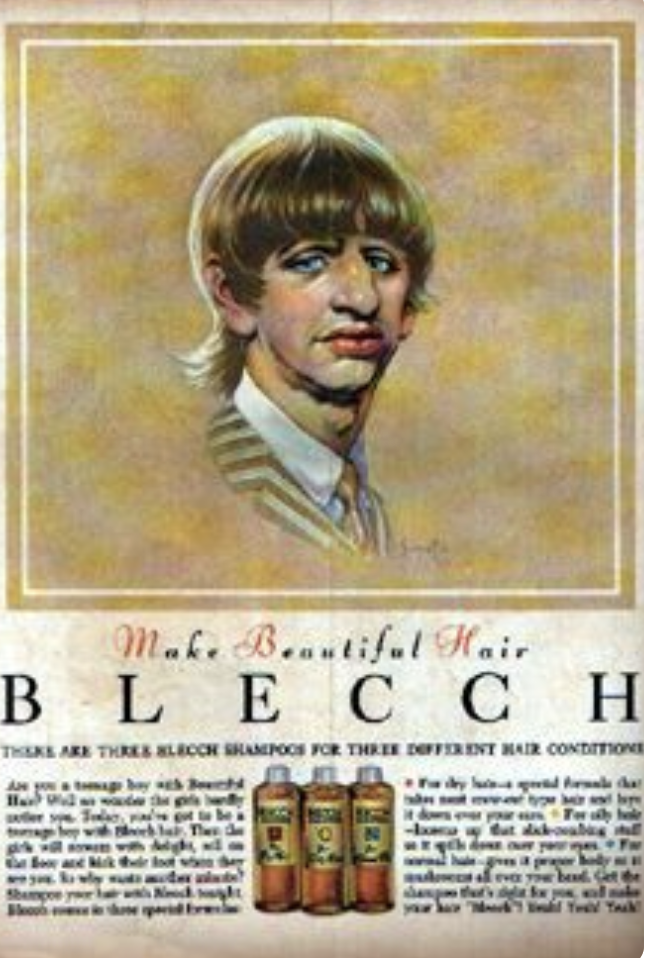

One of its “usual gang of idiots,” the caricaturist Mort Drucker, died April 9, 2020, at his Woodbury, NY, home. He was 91. His death was first reported by The New York Times, in a lengthy obituary. And on April 10, 2023, Al Jaffee, the cartoonist responsible for the ingenious Mad Fold-In that appeared on the inside of the magazine’s back cover and transformed an otherwise straightforward image with script into another image altogether, with surprising results.

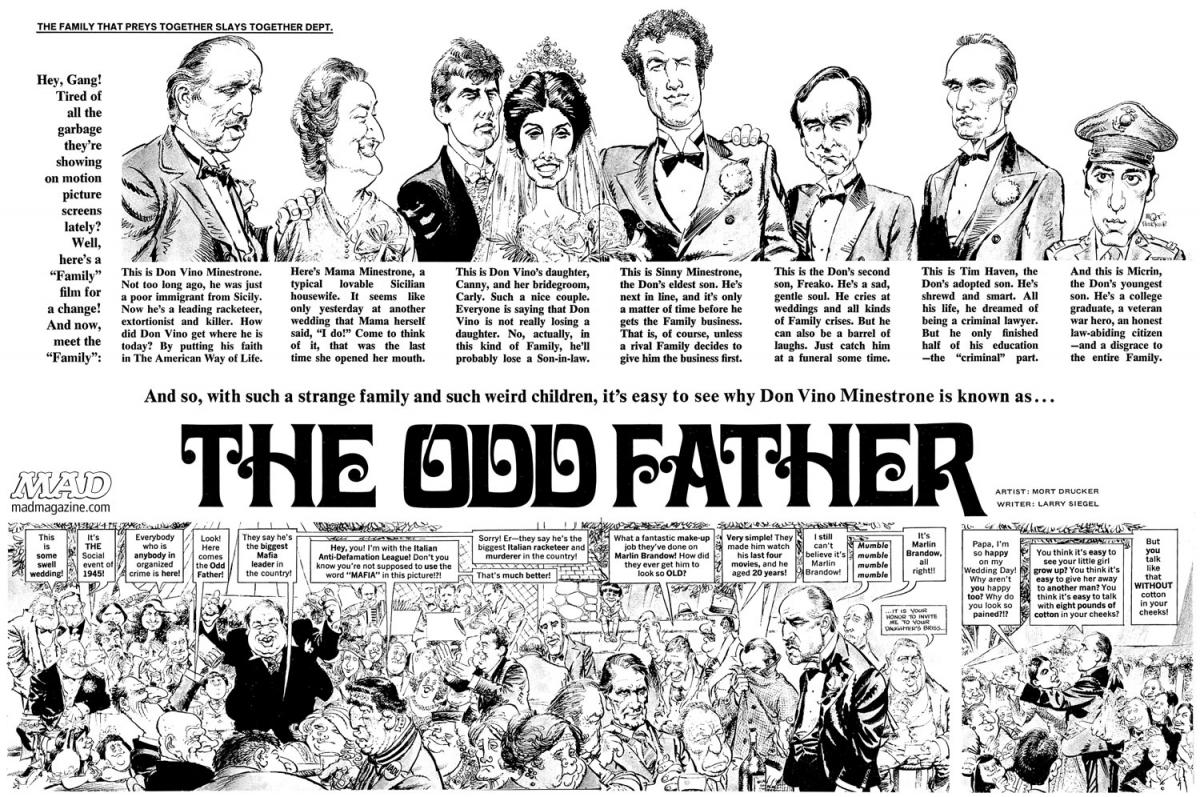

A book of his work, Mort Drucker: Five Decades of His Finest Works, was published in 2012. Drucker won numerous awards and honors including the National Cartoonists Society’s Cartoonists prestigious Reuben Award. Drucker’s most famous features were his movie and television satires, capturing characters from The Godfather (parodied as The Oddfather) to Star Wars (The Empire Strikes Out).

Mort Drucker’s artwork for The Oddfather in Mad’s Dec. 1972 issue

Michael J. Fox once told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that he knew he had made it when Drucker drew his caricature in Mad. Charles Schulz once wrote, “Frankly, I don’t know how he does it, and I stand in a long list of admirers … I think he draws everything the way we would all like to draw.”

Drucker’s work outside of Mad is also noteworthy. Among his most famous pieces was the key art for the 1973 George Lucas film, American Graffiti.

The magazine’s major contributors also included Don Martin, Al Jaffee, Frank Jacobs, and later Antonio Prohías, Dave Berg and Sergio Aragonés, each of whose names were well known to its readers. Editor Feldstein retired in 1984 and was replaced by Nick Meglin and John Ficarra, who remained at the helm for the next two decades. Other editors followed, but Mad’s circulation began a steady decrease as the years went on and reader tastes changed. (Gaines sold the magazine during the 1960s and it was henceforth published by DC, which itself became swallowed up by Time Warner; Gaines died in 1992.)

Listen: A popular Mad magazine recording of the 1960s, “It’s a Gas,” featured Alfred E. Neuman belching to a rocking beat

Mad appealed primarily to adolescents with its combination of topical humor, parody and outright daftness. Until 2001 it accepted no outside advertising so that it might continue to lampoon companies as well as celebrities and other sacred cows. Many of Mad’s articles exposed staples of American culture—nothing and no one was safe from its pointed humor, from hit movies to popular products to the media to politicians. Irony and skepticism reigned in Mad features.

Weird Al guest edited an issue of Mad

Upon the announcement of the magazine’s impending demise in 2019, Weird Al Yankovic (see photo above) tweeted: “I am profoundly sad to hear that after 67 years, Mad Magazine is ceasing publication. I can’t begin to describe the impact it had on me as a young kid – it’s pretty much the reason I turned out weird. Goodbye to one of the all-time greatest American institutions. #ThanksMAD.”

Related: Paul Krassner, a ’60s countercultural figure, once wrote for Mad

Each issue of Mad featured a fold-in on its inside back cover, designed by Jaffee, that Wikipedia describes as such: “In each fold-in a question is asked, often of a topical nature. The subject is illustrated by a picture taking up the bulk of the page, with a block of text underneath. When the page is folded inward, the inner and outer fourths of the picture combine to reveal an alternate answer in both picture and words. Jaffee’s precise layouts sometimes include false visual cues designed to trick the reader’s eye towards an incorrect solution.”

Jaffee, who holds the Guinness World Record for longest-ever career as a comic artist, turned 100 on March 13, 2021.

Watch: Mad‘s fans included Homer and Bart Simpson

Other regular features included “Spy vs. Spy,” “The Lighter Side of…,” “A Mad Look at….,” “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions” and many others. . Don Martin’s invented words for sound effects often found their way into the general culture, as did Mad’s usage of bizarre (but usually real) words such as potrzebie, poiuyt and axolotl.

The New York Times, in a 1977 article, wrote: “Mad’s consciousness of itself, as trash, as comic book, as enemy of parents and teachers, even as money-making enterprise, thrilled kids…Such consciousness was possibly nowhere else to be found. In a Mad parody, comic-strip characters knew they were stuck in a strip. ‘Darnold Duck,’ for example, begins wondering why he has only three fingers and has to wear white gloves all the time. He ends up wanting to murder every other Disney character.”

According to Wikipedia, “Mad’s satiric net was cast wide. The magazine often featured parodies of ongoing American culture, including advertising campaigns, the nuclear family, the media, big business, education and publishing. In the 1960s and beyond, it satirized such burgeoning topics as the sexual revolution, hippies, the generation gap, psychoanalysis, gun politics, pollution, the Vietnam War and recreational drug use. The magazine took a generally negative tone towards counterculture drugs such as cannabis and LSD, but it also savaged mainstream drugs such as tobacco and alcohol. Mad always satirized Democrats as mercilessly as it did Republicans.”

Mad’s approach to humor is said to have had a profound influence on later comedic institutions such as Saturday Night Live, National Lampoon and The Simpsons.

Watch: In 1977, publisher William Gaines recalled the origin of Alfred E. Neuman

Many Mad magazines and books are available here.

- Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan to Headline 2025 Outlaw Music Festival Tour - 02/03/2025

- Radio Hits in February 1965 - 02/03/2025

- AC/DC Expands 2025 Edition of ‘Power Up’ Tour - 02/03/2025

8 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationRIP MORT

you could always tell that he loved doing what he did. Almost as much as we loved reading about it.

MAD’s musical influence cannot be forgotten! Here’s Harold Bronson’s band, laying the groundwork for what became Rhino Records’ general attitude: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtFuMVxZdDk

I didn’t buy a copy of Mad Magazine once I graduated from high school, I guess because of other interests (girls, cars, music, etc), but it sure was a staple in my years between about 9 years old through 18 – everytime a “Spy Versus Spy” paperback came out (about 2-3 times a year), I was at the local magazine store (yes, published print was once the norm), and bought every copy during that period, ad well as my monthly copy of Mad.

The success of Mad Magazine was that it did not target any one group – everyone was fair game, and subject to Mad’s sharp wit and social commentary.

Thanks for another well-written, researched, and informative article from BCB.

The end of an era indeed.

The link to Mort Drucker’s NYT “lengthy obituary” is broken in the article text.

Fixed. Thanks, Batchman.

You wrote that “The magazine’s major contributors also included Don Martin, Al Jaffee, Frank Jacobs, and later Antonio Prohías, Dave Berg and Sergio Aragonés,” implying that Berg, like Prohías and Aragonés, arrived at MAD in the early 1960s. In fact, Berg was there from the start of the Feldstein era along with Martin, Drucker, Jaffee, Jacobs et al., but his “Lighter SIde” feature didn’t appear until 1961. Before that he was contributing regular feature articles, usually about some aspect of suburban life.

Listening to the “It’s A Gas” song, I clearly remember the record being included in a mid-60’s issue of MAD as one of those cardboard records that you could tear out and play on your phonograph. 12 year-old me was delighted.