John Hammond, in an undated photo

If the late Columbia Records talent executive John Hammond had signed any one of Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen, his legacy would be golden. To sign all three—as well as discover and/or foster the careers of such talents as Billie Holiday, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen and Stevie Ray Vaughan—puts him in his own special category.

This Q-and-A with the legend originally appeared in the September 30, 1972 issue of Record World, a music industry publication when Hammond was 61. We’re pleased to run a substantial two-part excerpt of it.

John Hammond is Director of Talent Acquisition for Columbia Records, the company he has been associated with almost continuously since 1932. His career, still very active, has included the discovery of many of the greatest American artists, from Billie Holiday to Bessie Smith to Bob Dylan to Aretha Franklin.

You’ve somehow survived in a very distinguished position at a giant record company, on and off, for some 40 years. How did you do it?

I think the way I’ve done it is by offending everybody. In my time I think I’ve offended just about everybody I’ve worked with. I was headstrong, and I liked jazz at a time when nobody else did and I liked chamber music at a time when nobody else did; and those are my two sort of special fields in music.

Let’s start from the beginning. How did you get into the music business?

I’ve been a collector all my life, since before I was ten. I had at one time about 33,000 records. Every nickel that I had went into buying records and hearing everything. By 1933, I was writing for Melody Maker, which was my idea of what a trade/consumer paper should be, because they had really rough critics. I was the first American correspondent they ever had that went to Harlem, and I came to the attention of Columbia Gramophone in England and they figured that maybe for a very cheap price they could get jazz records made in America. And Columbia knowing nothing about jazz anyway, they thought maybe I could do something for them. So I gave them a huge list of people I wanted to record, most of whom I didn’t even know. Just people I liked, like Benny Goodman, whom I had met once. I got all the groups together and supervised the damned things for nothing. I must have made 150 sides on that contract.

You weren’t making any money on this?

Not a nickel. I had a small income, and I lived on that. If there was anything left over I’d lend it to musicians, who were always broke in those days.

So here I was, age 21, a nut, a fanatic; people didn’t take me terribly seriously, and also they didn’t have to pay me, and that’s terribly important. And that’s the dreadful thing that’s happened to me all my life in the record business—I’ve never gotten properly compensated I don’t think.

I got my first real paying job in 1939, at $125 a week. The New Yorker did a profile on me, and so Columbia raised my salary. But I think they hired me for sound commercial reasons—they wanted Goodman, Basie and a strong jazz field, and I provided a lot of this for them.

How did you come upon Aretha?

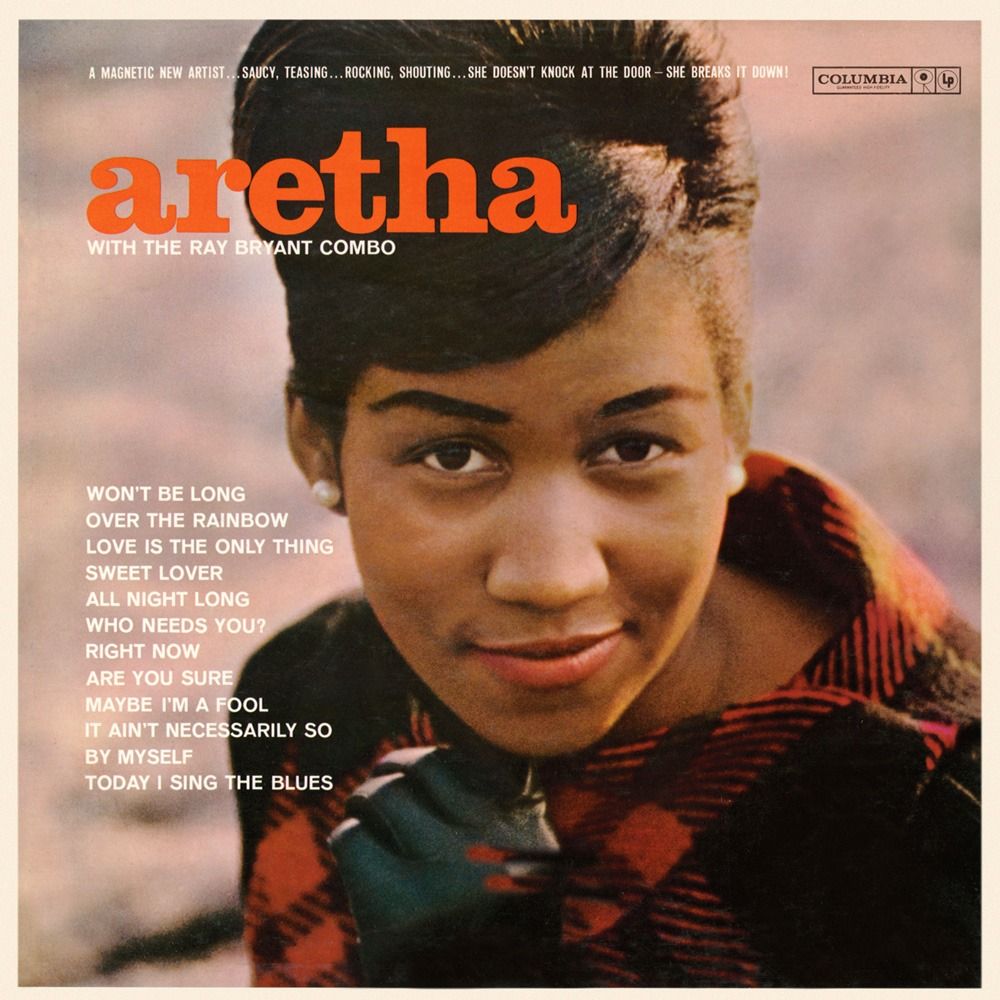

The cover of Aretha Franklin’s 1961 Columbia debut describes her as “a magnetic new artist”

Aretha is really one of the fascinating stories, because at that time [1960] I was sort of living in the past, you know. I was saying, gee there’s never been another singer like Billie Holiday or Bessie Smith, whom I had recorded in the early days.

But I’ve always been a freak for gospel music. So one day a songwriter named Curtis Lewis came in with a demo of about five of his tunes. The third tune was a thing called “Today I Sing the Blues,” and it was just this girl on piano. And I screamed! I said for Chrissakes who is this? He said: “She’s a 17 year old girl from Detroit.” And I said can she do anything else, and he said she was a gospel singer who sang with her father’s choir with Sam Cooke.

So I said, uh-oh, if RCA ever finds out about her, I’m in great trouble. It took me a while to find out where she worked, because I knew it was in Detroit, and I hadn’t heard the greatest things about the old man, the Reverend C. L., but I had his records on Chess, so I knew that he was a good artist in his own right.

Finally a woman by the name of Jo King, wonderful person, became Aretha’s manager. And she got Aretha to make a full demo, and this time I was even more knocked out. [Goddard] Lieberson was still President of Columbia and I said “Goddard, we’ve got somebody really major.” Mitch [Miller] was also impressed and Bill Gallagher, who was sales manager, didn’t care much one way or the other. But Jo King was a good businesswoman and Aretha got herself a good contract.

Related: Top music stars reflect upon Aretha’s passing

[The Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, opens on Christmas 2024 and early reviews—including Best Classic Bands‘—are touting Timothée Chalamet’s performance.]

How about Dylan?

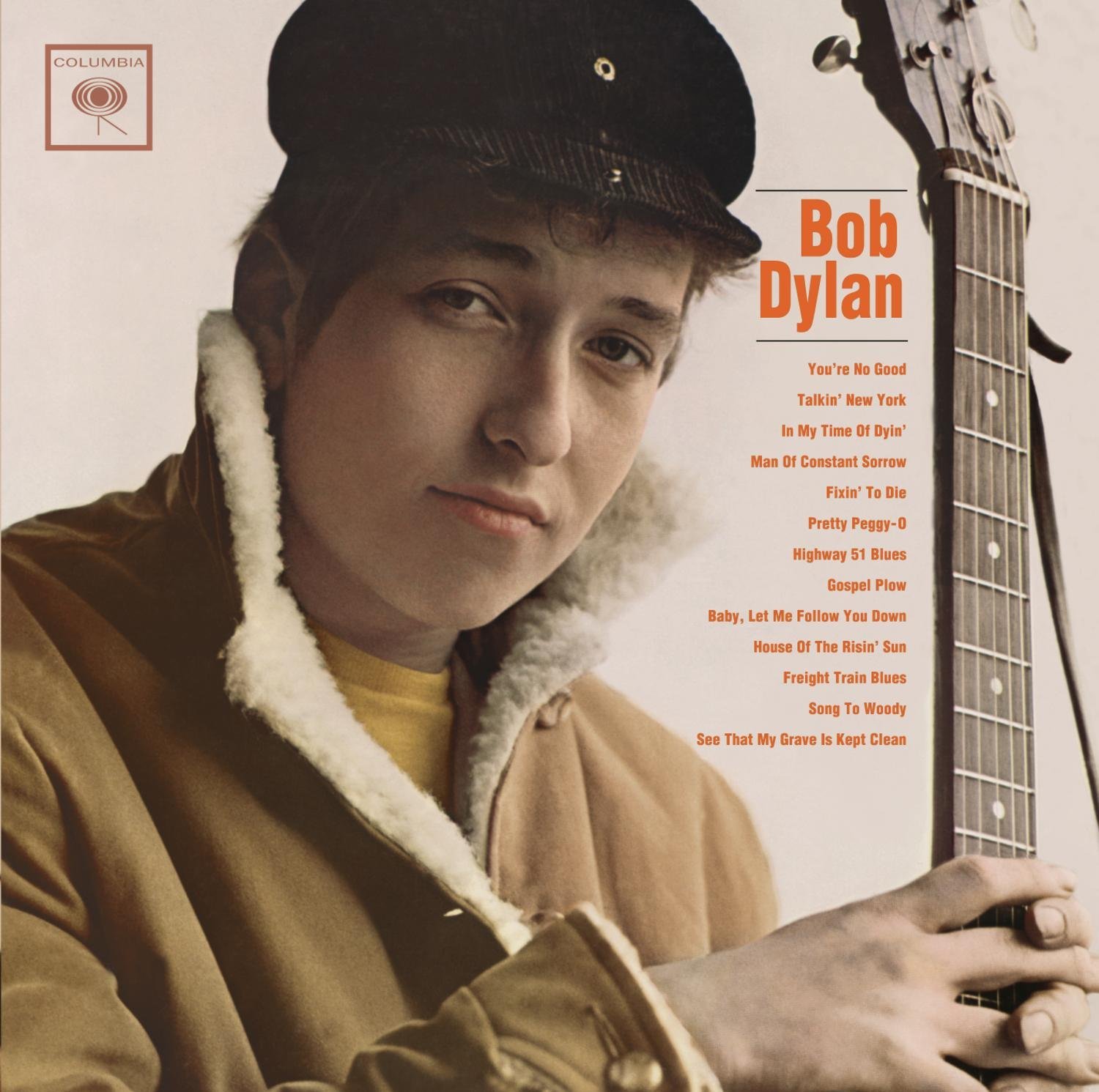

Bob Dylan’s self-titled debut album, released in 1962

I brought in Dylan and signed him, and this was over everybody’s dead body. One vice president at Columbia was annoyed at me because I had let Joan Baez go to Vanguard, and his son was at Harvard, and he thought the world began and ended with Joan, which it almost did–she was that good. But Vanguard offered her more money than I did—I decided I didn’t like her manager, who was Al Grossman.

Anyway, I got Dylan—this was long before Grossman had come into the Dylan picture—I must say that his first records didn’t sell all that much, but he got an awful lot of attention. And [A&R exec David] Kapralik sniffed that this was really something pretty special, so he sort of got in the way between me and Dylan. And by this time I didn’t get along at all with Grossman. I had given my blessing to Bobby going with Grossman because he had lined up a BBC documentary and a couple of thousand bucks for Bob which he needed badly. And so I bowed out.

Hammond was born on December 15, 1910 and died July 10, 1987. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationMy copy of the 2nd part of the Record World you did with Mr Hammond, in the 7 October 1972 issue, is missing page 20. It is an interesting article, and he deserves far more credit than he received.

Two things, one in the intro and one in the interview itself with the full realization you’re just reprinting the interview.

John Hammond did not discover Pete Seeger. He signed Pete Seeger to Columbia Records roughly around the 1960. Seeger had been recording since the ’40s, as a solo artist and with The Almanac Singers and then The Weavers. When Hammond signed him, he already had dozens of albums recorded for Folkways. Hammond in signing Seeger to Columbia was courageously ending the blacklist.

Hammond interestingly enough is wrong about Albert Grossman managing Baez. Her manager back then was Manny Greenhill.

Many thanks for taking the time to share that, PSB. We’ve amended the intro but left Hammond’s own words as-is.