Jim Croce ‘You Don’t Mess Around With Jim’: An Everyman Arrives

by Mark Leviton The myth of “overnight success” in the music business never seems to lose its hold on the public imagination. Today, when teenagers achieve break-out success from a single YouTube or TikTok video and “influencers” command huge audiences for their recommendations, the myth has become at least in part the new reality. It is in fact possible to “come from nowhere” and reach the pop charts in one bound, without ever playing a live show or using a recording studio that isn’t your bedroom laptop.

The myth of “overnight success” in the music business never seems to lose its hold on the public imagination. Today, when teenagers achieve break-out success from a single YouTube or TikTok video and “influencers” command huge audiences for their recommendations, the myth has become at least in part the new reality. It is in fact possible to “come from nowhere” and reach the pop charts in one bound, without ever playing a live show or using a recording studio that isn’t your bedroom laptop.

Back in the ’70s, what Joni Mitchell called “the star-making machinery behind the popular song” ground away more slowly. Acts, like the Philadelphia-born Italian-American Jim Croce, often served apprenticeships in dive bars and near-empty clubs trying to get noticed, and blew whatever they earned from day jobs making “demos” for the gatekeepers at record labels and radio stations. Mitchell had David Geffen to run interference so she could do her creative work, but managers and agents with that kind of drive and smarts were only available to a select few.

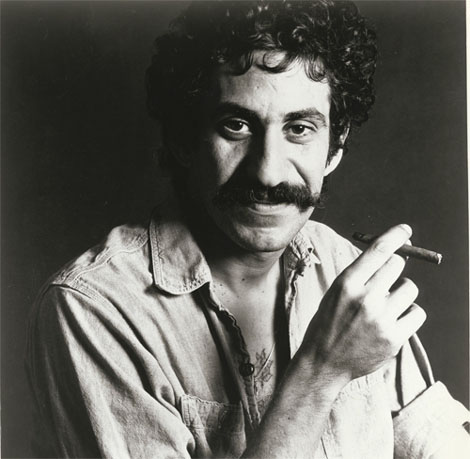

In 1971, Croce was one of those aspiring singer-songwriters who spent as much time in a series of dead-end occupations—truck driving, construction, military service—as he did playing music. The working-class Croce struggled for years to establish himself, as a solo artist or in a duo with his wife Ingrid, before he signed to the ABC-Dunhill label with the help of producers Terry Cashman and Tommy West, two talented hustlers who’d had their own winding path to some minor music biz success. Croce’s friend Arlo Guthrie once said Jim didn’t consider himself especially unique; his belief in himself as a “regular guy” was sincere.

Croce’s first recordings, 500 privately pressed copies of an LP called Facets in 1966, had been financed with a $500 wedding gift from his parents. They hoped to demonstrate his musical aspirations were a pipe dream, and he should find a respectable profession, using his college diploma in Social Studies from Villanova, but he sold all 500 copies and was encouraged by what attention he got in local clubs. He subsequently got a shot at fame with a Capitol Records contract, but nothing stuck until Cashman and West stepped in.

By the time Croce died in 1973 in a plane crash at the age of 30, he’d seen his records at the top of the charts, performed on big network TV shows, and toured America, ultimately deciding what he really wanted was to live up to his role as “family man” and quit the music rat-race. His letter to Ingrid, detailing his plan to get off the road, write short stories and screenplays, and stay home, arrived after his death.

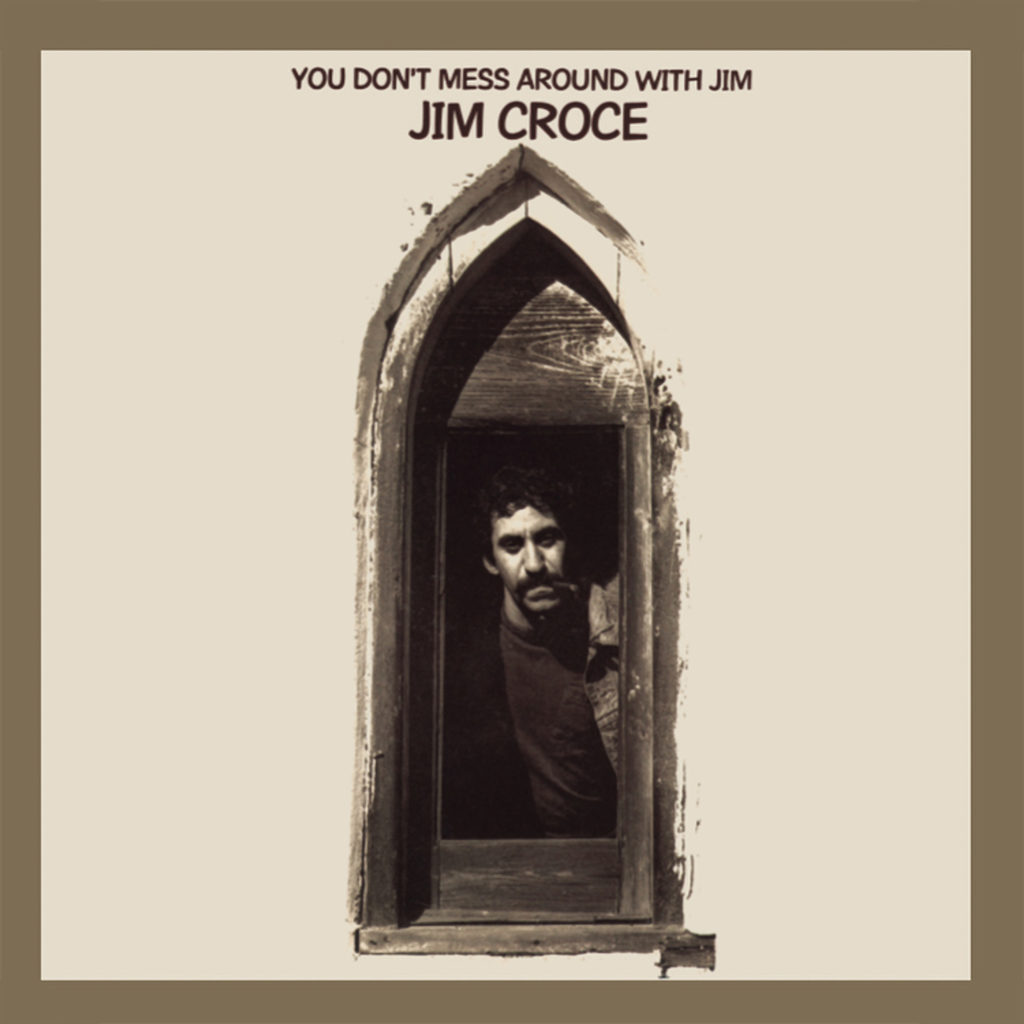

You Don’t Mess Around With Jim, recorded in autumn 1971 at the Hit Factory in New York City and released in April 1972, was the long-delayed commercial breakthrough from Jim Croce, and for most fans it seemed to come out of the blue. He wrote every song, performing with his simpatico lead guitarist Maury Muehleisen, drummer Gary Chester, bassist Joe Macho and several background vocalists, including songwriting great Ellie Greenwich and Tasha Thomas. Tommy West plays keyboards, guitar, bass and sings whenever needed, and Peter Dino is credited with the expert arrangements. There’s nothing flashy about the production; Croce’s affable, intimate vocal style, and his ability to write both humorous ditties and heartfelt love songs, puts the focus clearly on his raw talent and winning “everyman” personality.

Related: Jim Croce: What Might Have Been

The album’s title track leads off, a bouncy, lighthearted tune in the tradition of “Stagger Lee” or “John Henry,” the type of songs Croce absorbed during his early performing nights on the folk circuit. The words also recall those times he drove a tractor-trailer hauling stone from New England quarries, where in his words “the truck stops are like Fellini films.” Over a primal, forceful acoustic guitar/bass/drum opening, Croce sings “Uptown got its hustlers/The Bowery’s got its bums/42nd Street got Big Jim Walker/He’s a pool-shooting son-of-a-gun.”

The arrangement proceeds by careful addition. First lead guitar, then piano, enter, and by the time the backup singers come in with “say, Jack” we’re in a world where Ray Charles-style R&B meets Croce’s folk-hootenanny tenor, with maybe a nod to Bob Dylan’s raucous “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.”

The party atmosphere continues with the catchy wit of the chorus: “You don’t pull on Superman’s cape/You don’t spit into the wind/You don’t pull the mask off that old Lone Ranger/And you don’t mess around with Jim.”

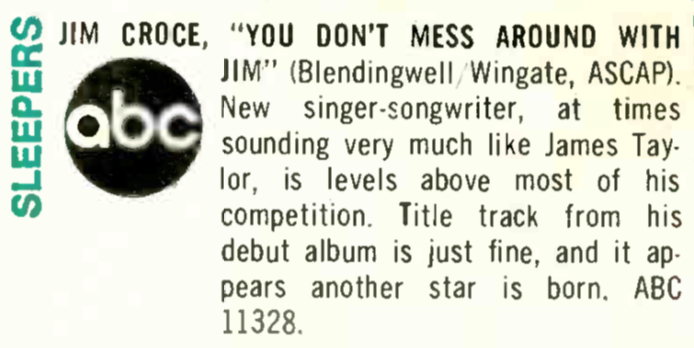

“Tomorrow’s Gonna Be a Brighter Day” could be a simple apology to Ingrid for his failings as a father and husband: “I’m gonna make up for all the hurt I brought/I’m gonna love away all your pain.” But amid his promises Croce also inserts a “it’s meant to be” caveat when he sings “Nobody ever had a rainbow, baby/Until he had the rain.” Unlike the opening track, this is a straightforward James Taylor-type arrangement, with excellent bass playing and interaction from the two acoustic guitars.

“New York’s Not My Home” is a clearly autobiographical lament: “I lived there ’bout a year and I never once felt at home/I thought I’d make the big time/I learned a lot of lessons awfully quick/And now I’m tellin’ you they were not the nice kind.” The string arrangement and understated accompaniment recall classic Jimmy Webb/Glen Campbell collaborations like “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” Following a similar theme, the frantic jokes of “Hard Time Losin’ Man” come quickly, as the protagonist is swindled in a car deal, cops some “super fine dynamite from Mexico” that turns out to be oregano, and complains, “Sometimes I feel like I should go/Far, far away and hide/’Cause I keep waiting for my ship to come in/And all that ever comes is the tide.”

The first side of the original vinyl concludes with two short ballads that in plain language deal with lost love. “Photographs and Memories” has a gorgeous melody and resignation in the lyrics: “Summer skies and lullabies/Nights we couldn’t say goodbye/And of all the things that we knew/Not a dream survived.” “Walkin’ Back to Georgia” imagines a poor soul on the road to Macon, yearning for his former girl, hoping to reunite with “the only one who knows/How it feels when you lose a dream/And how it feels when you dream alone.”

Like Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee,” “Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels)” begins with the speaker asking for help from a telephone company employee. Croce skillfully injects drama and detail from the start: “Operator, could you help me place this call?/See, the number on the matchbook is old and faded/She’s living in L.A. with my best old ex-friend Ray.” Once again, Croce blends the sardonic and sentimental as his protagonist explains to a total stranger how he’s gotten over his love with “I’ve learned to take it well/I only wish my words could just convince myself.”

Released as a single, “Operator” made it to #17 on Billboard’s single chart, but the following track, “Time In a Bottle,” issued on 45 rpm after Croce’s death, got to #1. Borrowing a progression from “My Favorite Things” for the tender guitar intro, Croce softens his voice for a beautifully restrained effect. The tragically ironic words “There never seems to be enough time/To do the things you want to do once you find them” are certainly one reason for its posthumous success and continuing appeal.

Listen to the demo of “Time in a Bottle”

The opening riff of “Rapid Roy (The Stock Car Boy)” is stolen outright from Chuck Berry, and the lyrics owe more than a little to his rapid-fire joshing: “He got a tattoo on his arm that says Baby/He got another one that just say Hey.” Not for the first time on the album, Croce puts on a faux Southern-Black accent, a choice for singers in the ’60s and ’70s (hello, Mick Jagger!) that doesn’t impact quite the same way today.

“Box #10,” with Jim Ryan doing a great job subbing on bass, is another hard-luck story with details from Croce’s own travels, this time transposed to the Midwest: “Out of Southern Illinois come a down-home country boy/He’s gonna make it in the city playing guitar in the studio/Well, he hadn’t been there an hour when he met a Broadway flower/You know she took him for his money and she left him in a cheap hotel.”

The last two tracks, “A Long Time Ago” and “Hey Tomorrow” (with studio musician Harry Boyle’s pithy electric guitar), are perfectly serviceable but don’t add a lot to what we’ve already heard. Yet another sad-sack stand-in for Croce asks for sympathy: “I’ve been wasted and I’ve over-tasted/All the things that life gave to me/And I’ve been trusted, abused and busted/And I’ve been taken by those close to me.”

The follow-up disc, Life and Times, was released two months before Croce’s fatal crash (which also killed Muehleisen and four others), and it was a solid hit as well, powered by the #1 “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown.” It’s a damn shame Croce didn’t live to reap the full benefits of such a confident pair of LPs. With more time, if—a big if—he’d chosen to pursue a conventional career full-throttle, he might have taken his place as an equal of James Taylor, Gordon Lightfoot, Paul Simon, etc. His son Adrian James “A.J.” Croce has had a distinguished career in music and is well worth checking out. Jim Croce died just before A.J.’s second birthday, leaving Ingrid to oversee a series of posthumous releases, a heartbreaking VH-1 “Behind The Music” episode, and serve as caretaker of his legacy to this day.

A 50th anniversary edition of the album, complete with matching alternate gold-bordered cover artwork, is available here on vinyl, CD and cassette. Croce’s catalog is available here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationBeautiful article about a beautiful man. Jim might have been the most down to earth artist this world has ever known. Making a blue collar living with a white collar education gave him amazing discernment about the rat race and how evil it truly is. He was an angel trapped in flesh. An ambassador for Truth. Keep UP the great work.

Thank you Mark and BCB, for this informative article celebrating Jim Croce, a truly relatable and introspective artist, whose songs and storytelling have made an indelible mark on most baby-boomers, and many younger generations as well.

A truly gifted singer/songwriter, who is still listened to, and enjoyed, 50 years on.

In late January 1974, “You Don’t Mess Around with Jim” was the #1 album on Billboard. #2 was “I Got a Name”.

It wasn’t a big hit, but “Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues” is my favorite Croce song.

Jim’s albums were not ‘hits and filler’. As the ad copy for a Jerry Lee Lewis comp stated, “All Killer, No Filler!”

Gone too soon.