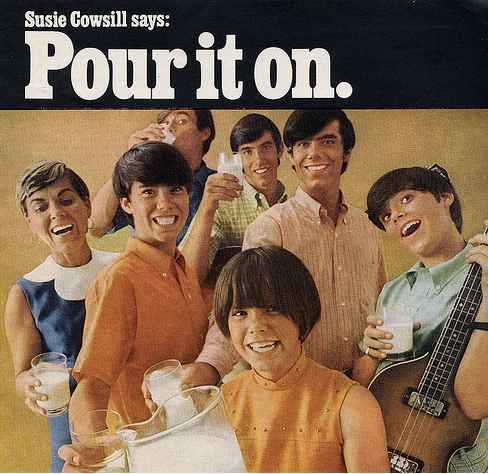

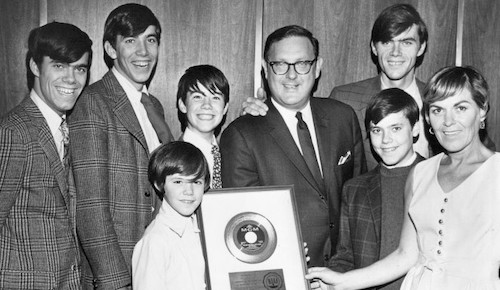

Anyone who has watched the 2011 documentary Family Band, the real-life tale of the group called the Cowsills, knows that the true behind-the-scenes story of the singing siblings—and their mom—was often at odds from the wholesome good-time image they projected in public. Formed in 1965, by brothers Bill, Bob and Barry Cowsill, with a fourth brother, John, joining a bit later, the Cowsills, from Newport, Rhode Island, struggled for a few years before finally hitting it big on the charts. Moving away from the indie labels that had failed to break them, the Cowsills—who were joined, in quick order, by another brother, Paul, the youngest sibling, Susan, and their mom, Barbara—signed with MGM Records and scored a #2 Billboard hit in 1967 with “The Rain, The Park and Other Things,” a sunshine-pop classic drenched in harmony and melody to spare. (Another brother, Richard, was not a member of the group.)

Anyone who has watched the 2011 documentary Family Band, the real-life tale of the group called the Cowsills, knows that the true behind-the-scenes story of the singing siblings—and their mom—was often at odds from the wholesome good-time image they projected in public. Formed in 1965, by brothers Bill, Bob and Barry Cowsill, with a fourth brother, John, joining a bit later, the Cowsills, from Newport, Rhode Island, struggled for a few years before finally hitting it big on the charts. Moving away from the indie labels that had failed to break them, the Cowsills—who were joined, in quick order, by another brother, Paul, the youngest sibling, Susan, and their mom, Barbara—signed with MGM Records and scored a #2 Billboard hit in 1967 with “The Rain, The Park and Other Things,” a sunshine-pop classic drenched in harmony and melody to spare. (Another brother, Richard, was not a member of the group.)

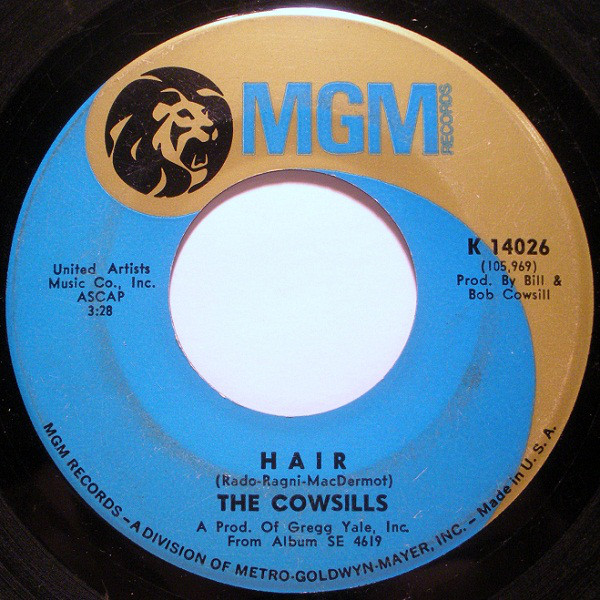

The following year, they hit the top 10 again, this time with “Indian Lake,” a bubblegummy trifle, and then, in 1969, returned to #2 with the title song from the hit Broadway musical Hair. But that was, for all intents and purposes, as far as they got before the world that had promoted and shielded them so well collapsed around them. Much of the blame—and the documentary brings home this point—for that has been historically laid at the feet of the father of the Cowsill kids, William (known as Bud), a tough taskmaster who often made life difficult for his children, ultimately leading to a falling out with Bill Cowsill and (after a short-lived switch to London Records that produced no hits) soon led to the demise of the group in the early ’70s. The Cowsills broke up, the members mostly went on to lead their individual lives, and for many fans they were forgotten.

Until they weren’t. There would be various partial reunions over the years, recordings that failed to find release and, ultimately, a revival of interest in what they had to offer. Some were still active in music after the band broke up—Susan Cowsill, in particular, enjoyed a busy solo career, notably as a member of the Continental Drifters, a fine ’90s Americana band (before anyone called it Americana). Bob and Barry continued to perform and record music and John Cowsill, a super drummer, put in several years as a touring member of the Beach Boys. (He performs today with Vicki Peterson of the Bangles, his wife.) Brother Paul, however, left the music business to take up work in construction, while Bill Cowsill experienced personal hardships and illness. (Barry died in 2005, and Bill the following year.)

The Cowsills as a band, though, were not ready to be consigned to history. Starting in the late ’80s and continuing into the ’90s, they came back, tentatively testing the waters at first and eventually solidifying as the trio of Bob, Paul and Susan Cowsill, which continues to this day. There have been excellent new releases, including the “lost” 1993 album Global and the all-new 2022 album Rhythm of the World, and the siblings have toured heavily, including several seasons as members of the Happy Together Tour troupe, alongside the Turtles and other artists of the ’60s. They sound better than ever—true to the music they created back in the day, but brought up to date.

In 2024, Best Classic Bands editor Jeff Tamarkin spoke at length with Bob Cowsill about the band’s history—the ups, the downs and the all-arounds. They also spoke about the then-new release of Global, the album they recorded more than three decades earlier that had been shelved for way too long. That first part of the conversation, focusing on Global, can be found here.

Best Classic Bands: The Cowsills made other recordings before signing with MGM Records and having your big hits. What was the situation leading up to that signing?

Bob Cowsill: The climb to that point took so long. MGM Records was our third label, so we were veterans of being dropped by labels and putting songs out that didn’t do well. All through high school and grade school, we were putting out records and being dropped. “OK, that didn’t work. Well, let’s try this. Oh, that didn’t work.” When we got dropped by the second label, Philips, that’s when we met Artie Kornfeld, who wrote “The Rain, The Park and Other Things” and produced that for us and took it to MGM. [Ed. note: the song was co-written by Steve Duboff.] The group that got dropped from two labels are the four Cowsill brothers. Then it was decided to put our mother in the band. We were not in on this decision. We were against it. So was Artie. But mom’s going to be put in the band. Now we’re our own thing.

What were the pre-MGM days like for the Cowsills?

The band that got dropped from two labels did not sound like the band that recorded “The Rain, The Park and Other Things.” It just didn’t. We were into harmonicas. We were into Jimmy Reed. We were into Motown. No one’s ever heard these songs from 1964 when I was 14. We were from Newport, Rhode Island. We didn’t even know there’s racism out there yet, or that there’s unrest. We were so blocked out of everything in those early days. News wasn’t reaching us from the outside. We were on an island in Rhode Island.

When you went to MGM, did you have any control over what you recorded, how it was produced, etc.?

We had control. Artie was our producer. My brother Bill and I were going to be producers, too, with Artie, but Artie was our producer. I was 17. Bill was 18. Everyone else was younger. We learned from Artie; he spent time in our house with us, teaching us about harmony, and this and that. When MGM came along, we had a hit, and that’s great. But that was going to fall apart immediately, because Artie was going to get in trouble for telling us about pot, and Dad was going to fire Artie after having a million-seller. He got a nice buyout. But now what? Now it was thrown to me and Bill. We had total control in the studio. We did all the arrangements in terms of vocals. And when we were with the orchestras, we were with these wonderful arrangers, Artie Schroeck and Herb Bernstein and Charlie Calello. We were arranging our songs on our albums, because we stepped into the studio during [what] we called the “Wouldn’t it Be Nice” days of Brian Wilson, where we were going to use all these studio musicians. That was a shock to walk into the “Rain, The Park and Other Things” session with [arranger] Jimmy Wisner, with a conductor at a podium with 30 musicians in front of him, strings and harps. “1, 2, 3, 4,” here comes “The Rain, The Park and Other Things.” It’s just like you heard on the record. Bill and I were sponges for this stuff. That was amazing.

That was recorded live in the studio without overdubs? That really is pretty amazing.

They did things in three-hour sessions; three hours to get one song done. The orchestras had their charts, and they were so good. Yes, it’s arranged exactly like you heard it. For [the 1968 single] “We Can Fly,” Bill and I had total control in the studio. “Indian Lake,” we did not have control of the studio because we needed a hit. For “Indian Lake,” they got Wes Farrell to produce. He had his own little Wrecking Crew, musicians he used. “Indian Lake” was not the greatest thing ever, especially lyrically. But it was a pop, summer, fun hit. Bill and I had nothing to do with it in terms of producing other than the vocal arrangement, which we always did. That was our thing. But it was a hit.

Let’s get back to “The Rain, The Park…” What did you guys think of that song when Artie brought it to you?

We loved it. Remember, we were a bit overwhelmed with recording with Jimmy and the orchestra. We were a pop band with our guitars and drums and bass. Now we’re this band. The song was beautiful, and the recording was so good, the sound. Mom was still not in the group when we recorded that song. Then Mom came into the group.

You said before that you were against her coming in. Why?

We were teenage guys. How do you think we’re going to react? We’ve been dropped from two labels. We’ve had three releases stiff. And this is what they came up with to fix all this? You can imagine. Of course, historically, this is all going to work out fine. But now they were going to put Mom in the group. And we were told that. No one asked us. In she comes. She’s never done this. We go back into the studio. Got to bring “The Rain, The Park and Other Things” back up and get Mom on it. You can’t just say she’s on it. Barry and John have young voices. Susan’s not on “The Rain, The Park…” She’s only six. So Mom did the melody, but she couldn’t do it alone. So what you hear is me. I had to go out there and get right behind her, right next to her ear, both in headphones. I just said, “Listen to me.” What you’re hearing is me and Mom singing that melody part. I got her through it by doing it that way, and it ended up being great. MGM took it lock, stock and barrel: the song, the group, the mom, and put a big campaign behind it. We flew for the first time in 1967 and did MGM promotional events and were touted as the next big thing. We’d been touted as that before so our heads were fine. We’d been through it.

That single came out in 1967, the year of Sgt. Pepper, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors. You really existed in a different world, but you somehow managed to find your own way.

Actually, it was going to follow us through our life. I think we came in as a breath of fresh air.

Jumping ahead two years, how was the title song from the Broadway musical Hair brought to you?

Jumping ahead two years, how was the title song from the Broadway musical Hair brought to you?

When “Hair” came to us, we were not living the life of we need a hit. We were past that. If you get one, good, but you can’t live your life like a record company wants you to live. We were always on tour. We were still fine. “Hair” was an assignment. At the end of the “Indian Lake” tour in the summer of ’68, we were going to go to San Francisco and tape a television special. [Then] it’s going to sit for months. Carl Reiner [producer of the show, titled The Wonderful World of Pizzazz] asked us to take “Hair” from the Broadway musical, which we hadn’t heard about, into the studio and do something we could lip sync to on the TV special, because it’d be fun to put us in wigs and have fun with the Cowsills in this song, because of the lyrics and the contrast. We got the song. We went down to whatever studio it was. Recording was hard back then: take after take after take. So we went in the morning the first day. We finished at the end of the second day. Mom’s not even on here, but we needed to get Susan on it. What do we give her? We gave her [the line] “and spaghetti.” What you hear, the record is done. While we were on the road, we listened to it. This is very cool, we think. We sent it to MGM, and they sent it right back. This is not “Indian Lake.” Their attitude was, “Who is this?” Back it comes. “Oh, they don’t like that? OK, we’ll give them something else later.” We told this story to WLS radio [in Chicago]: “We made this record. MGM hates it.” “Well, let me play it. I’ll see if it’s good.” He [the disc jockey] put it on the radio and challenged his listeners, “Who is this?” Well, no one could figure it out. He got in trouble. You’re not supposed to play unreleased material during those days, and he did. But anyway, the special was coming in May. No one knew that Three Dog Night was doing “One.” The Fifth Dimension was doing “Aquarius.” Oliver was doing “Good Morning, Starshine.” We didn’t know these songs. We were isolated; we lived in a bubble. So now, with the TV special coming, MGM’s going to get smart. Maybe they got wind that, look, there is kind of a “Hair” phenomenon approaching. And we’re part of it, unbeknownst to them. And with the TV special, the performance, it became one of our fun videos. We didn’t do videos back then, but we have a video of that TV special, [wearing] wigs. They released it, and the thing’s our biggest hit of all time. We blew through those two days in the studio and ended up doing something that was going to be a big deal. So you never know what you’re working on.

In “Hair,” there’s a line that goes, “It’s not for lack of bread, like the Grateful Dead.” Did you have any idea who the Grateful Dead were when you sang that?

We did ask, why the Grateful Dead? We knew who they were because we had young open minds about music. We took everything in, including them. But you’re right. It was a funny line to us. We don’t know why they smacked them. It looked like a hand slap to the Grateful Dead. But we didn’t know “Hair” was from a musical.

Watch the Cowsills cover the Beatles’ “When I’m 64” on The Mike Douglas Show in 1970

Why do you think it all fell apart for the Cowsills in the early ’70s?

The fact that it went as long as it did is a really good story. It’s a story of survival and recovery. First, Dad fired Artie and it was back to Bill and Bob. MGM was freaking out. We needed a hit. “Indian Lake” came out. Now what? Well, “Hair,” our biggest hit ever, in 1969. We were riding high. All the teen mags loved us, luckily. Television shows loved us. Mom’s in the group. Who doesn’t like that group on TV? We did Ed Sullivan, Jonathan Winters, Kraft Music Hall, Hollywood Palace, Dick Cavett and Mike Douglas, all of them. Through all of that was a very, very harsh, unstable foundation under all of it that, causing interruptions in our career. Me and Bill, especially, were fighting with Dad and dealing with this and that. It was dumped in our lap after “The Rain, The Park…” We loved recording, writing. “All right, give it to us. We’ll take it. We’ll make an album.” We made the We Can Fly album. We know how to do that, and we did, but our albums didn’t sell well. We were not an album group. We were a singles group. The album got great reviews. Did it sell a million? No. Does that mean you did a bad job? No. So that’s why it fell apart after “Hair.” I’m 19. Bill’s 21. The teenage boys were young men. And this business with Dad, this is not going to end well. And it didn’t end well. You can only take so much. [Ed. note: In 1970, Bud Cowsill, the father of the Cowsill kids, fired Bill Cowsill after an argument and the group continued briefly without him before splitting.] Bill couldn’t take it anymore. We had been together [in a band] since the age of seven and eight. It’s like breaking up Lennon and McCartney. Bill was going to go on just like Lennon did and make records. I’m going to go on just like McCartney did with the guys. We’re artists. We’re still them. But this fractured that relationship to death. It was over. It was dead. [Dad] goes, “It’s over.” It happened in one morning. That’s just your life as a kid. Dad found pot in Bill’s car. He gathered it up. He put it on the living room table in the middle to show the little mound. He called us all in and declared that this is what happens when you break the rules in this family, and he threw Bill out of the group, out of the family. Everyone was in shock. There’s so many of us in the group on the tour, it was not a big deal. No one even noticed in most of the places that this had happened, this terrible thing. A lot of this had to do with drugs. We lived [in the ’60s]. We were in it. So this thing fell apart during the ride of our biggest hit. We were [working on a] live-in-concert album, which I’m going to have to finish alone, and this thing is going to head south. We got dropped from MGM and picked up by London Records. First American act signed with London Records. We put two albums out, which is the Cowsills basically trying to reinvent themselves in public. No one bought it. It’s over. And thank God for the Partridge Family, because they arrived right there.

OK, I’m glad you brought that up. To this day, you cannot see the name Cowsills without seeing “the inspiration for the Partridge Family.” Did the creators of the Partridge Family study you? Did they consult with you? Or did they just say, let’s put together a family group that looks and sounds like the Cowsills?

They consulted. They came to our house in Santa Monica. A very young 20-something Michael Eisner [future CEO of The Walt Disney Company] was in that group of young men that came to our door. They had an idea for a show, a family band. Mom’s in the band on a bus. They’re checking us out. But they didn’t want us in the show. They wanted Susan, maybe, because she’s cute. They weren’t going to have [our] Mom. That was [going to be] Shirley Jones from the get-go; that was a Shirley Jones vehicle. They didn’t know who we were and we didn’t know who she was. Anyway, we turned it down. They turned us down for their reasons. Dad was never going to let this go without Mom being included and the boys. So they took Wes Farrell and Tony Romeo, who wrote “Indian Lake,” and they wrote “I Think I Love You” [for the Patridges] and went to work in the Partridge Family world. But I have to tell you that we are honored by that because we were collapsing when they arrived. And I’ll say the opposite of what you said: You couldn’t read a Partridge Family article for years after that without reading about the Cowsills. We were very grateful for that because it kept our name out there. David Cassidy said, “Please don’t ask me about that family [the Cowsills] anymore in these interviews.” So they took our team and ran with it, had the hit, kept our name in the press. But it all fell apart harshly [for the Cowsills]. People weren’t talking to each other and I didn’t see anyone for a long time. It hurt so much.

The Cowsills have been doing the Happy Together Tours for years. How do you like going on the road as part of a package tour of older acts?

It’s a gift. We tried to get on that tour for three years. You’ve got to audition. You’ve got to sell it. And we don’t mind. We know we can pass auditions. We open the show because we’re kind of fun. We love to get the party going. And we’re very happy people. It’s good to have happy people. The songs of the ’60s are driving the whole tour. The Happy Together tour sells out because it’s good. [Tickets are available here and here.]

The Cowsills’ recordings are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationI LOVE the song, Hair, which is my favorite. I went to Hollywood Professional School in the ‘60’s with this group for 3 years, I think. They weren’t approachable, rather snobby for an “average” person like me. As far as their songs, they were great while it lasted.

I LOVED listening to “Hair! Hair! Hair Hair!” bouncing around my quad system in the 70s.

And let’s not forget, The Cowsills did the original ‘Love, American Style’ theme song. It might have been a single, as it was on one of their ‘Greatest Hits’ LPs.

Bill Cowsill had a decent career in Canada as part of the groups Blue Northern and The Blue Shadows. He had a very impressive “country voice”.