‘Ziggy Stardust’: An Interview with Engineer Ken Scott

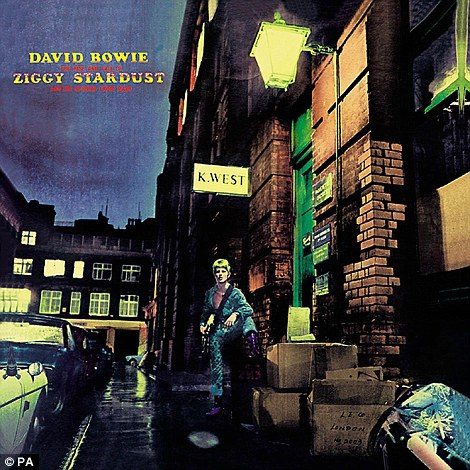

by Harvey Kubernik Warner Music Group (WMG) and the estate of David Bowie have signed a global, career-spanning partnership for the legend’s recorded music catalog. With this deal, Warner Music will now have worldwide rights to five decades of Bowie’s work, including his 1972 landmark album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Warner Music Group (WMG) and the estate of David Bowie have signed a global, career-spanning partnership for the legend’s recorded music catalog. With this deal, Warner Music will now have worldwide rights to five decades of Bowie’s work, including his 1972 landmark album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

The album was recorded at Trident Studios, London, between November 8, 1971, and February 4, 1972, with a lineup of Mick Ronson (guitar, piano, backing vocals), Trevor Bolder (bass), Mick Woodmansey (drums) and Rick Wakeman, harpsichord on “It Ain’t Easy,” with backing vocals by Dana Gillespie on same. In addition to performing vocals, Bowie played guitar and saxophone, with arrangements by Bowie and Ronson.

Released in America on RCA Records on June 16, 1972, the album marked the true arrival of Bowie in the United States. The popularity of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars was aided by glowing print reviews and a U.S. tour in winter of ’72.

This author conducted an interview in 2009 with and Ken Scott, who engineered and co-produced Ziggy. He reminisced about Bowie’s remarkable year of 1972.

Ken Scott: First and foremost, I couldn’t see that he’d ever be as big as he turned out to be. David was a nice guy and had a certain amount of talent. That was it. It wasn’t until we started to get [1971’s] Hunky Dory together that he was starting to find his own way. I suddenly saw a unique talent.

For Ziggy, David told me going in, “I don’t think you’re going to like this one. It’s much more rock ’n’ roll.” And there were only a few demos. We just flew by the seat of our pants. On Ziggy, one of the tracks, ‘It Ain’t Easy,’ was a left over from Hunky Dory.

Hunky Dory was a little more laidback. It was softer and gentler overall. But you had something like “Queen Bitch,” which could easily have fit on Ziggy. As well as my changing little things, Woody played different. So that changed things. It makes the whole thing. And everyone changed and that’s what makes Ziggy that much different sounding than Hunky Dory. It’s the playing. It’s the sound in the studio. It’s how I affected it in the control room. It’s always down to everyone and always a team effort.

Looking back on this period, one of the things that has fascinated me was—and I didn’t realize it until recently—the way piano changed David’s music. You take Hunky Dory, which had Rick Wakeman on it. He is a fantastic, more classically oriented pianist. His piano on “Life On Mars” is unbelievable.

Then you go into Ziggy, with Bowie and Ronno [Ronson] playing, and it’s really simplistic because they weren’t pianists. Neither of them was particularly awe-inspiring, so the piano is very simple on Ziggy. But then you go to Aladdin Sane and Mike Garson is on board and it completely changes the whole feel of it. The Beatles kind of grew by using different instruments. Bowie changed and grew by using different people playing. It’s bizarre. His use of keyboards really does sort of cover his growth and how he changed.

Then you go into Ziggy, with Bowie and Ronno [Ronson] playing, and it’s really simplistic because they weren’t pianists. Neither of them was particularly awe-inspiring, so the piano is very simple on Ziggy. But then you go to Aladdin Sane and Mike Garson is on board and it completely changes the whole feel of it. The Beatles kind of grew by using different instruments. Bowie changed and grew by using different people playing. It’s bizarre. His use of keyboards really does sort of cover his growth and how he changed.

There’s a lyric line from “Alley Oop” by the Hollywood Argyles, a record Kim Fowley co-produced and co-published, heard in “Life On Mars” on Hunky Dory. There’s another Hollywood Argyles record Fowley was involved with, “Sho’ Know a Lot about Love” that influenced “Moonage Daydream.”

A version of Fowley’s horn arrangement was utilized. On Kim’s production of the Hollywood Argyles, a baritone and flute play the same line together. And that solo was used for that same concept for the solo in “Moonage Daydream,” but it was a couple of octaves apart, and David playing a recorder instead of a flute along with the baritone.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Ziggy Stardust

To me, the thing that makes the album stand up after all this time is Bowie’s vocals. Generally speaking, 95 percent of them were first takes. They are real. They are human. They get to you. They pull you in. Let’s face it. If the vocal was bad we would have redone it. They aren’t bad. They are amazing. We didn’t need to. That probably comes from him not wanting to do it again. He just put his heart and soul into it straight off. It was whatever felt right. There were no rules. I just did whatever I wanted to do.

I was able to make suggestions artistically and musically that I would previously had to have gone through a middle man, the producer. Woody Woodmansey says, “You had to get everything done quickly ’cause he got bored.” And you only had a few attempts at something to get it right.

Mick’s arrangements were amazing. He wasn’t trained so he didn’t know rules, so anything went. If it sounded good, that’s the way he wanted it. Which was very much like the Beatles. They didn’t know the rules.

David didn’t like going to the mixing sessions. That was amazing, the trust that David put in me, just leaving me alone completely. But that trust was mutual. I attempted to allow him that freedom in the studio so it worked both ways. He had the studio to play with. I had the mixing room to play with.

David never once said, “I’d like it a bit more like this…” David understood collaboration. Look, the team of us—David, Ronno, Woody and Trevor—was an incredible period. It really worked well. The performances were superb. Musically it would stand up.

I can’t remember who came up with the final sequencing. Because it was on vinyl, we were limited to how we could set up running orders. We had to try and keep an equal amount of time on each side. And so, when they were practicing or rehearsing a part, I would sit there and take songs, work out timings and, “OK. We can put these together and these together. Or we may be able to swap that song with that song.” I was constantly setting up what kind of songs we could have on either side.

At Abbey Road [Studios], it used to be five seconds between every track. It had to be exactly five seconds. And there were times when having that five second delay between first song and second song, whatever, felt right. There are other times when you wanted something to come in faster. The running order was decided before mixing, ’cause when I was mixing.

Generally, it would be on the beat, sometimes a bit late and sometimes right on top. But I always tried to get it in time so your foot would be tapping and then you hit the first downbeat of the next track and carry on that way.

At Trident the control room was still above the studio, where we were looking down, so it was very much like Abbey Road’s number 2 studio in design. They were both great studios. There was something for me about number 2, the history of it. No matter how many times I go there I would stand at the top of those stairs and the hairs on the back of my neck would stand up. For me personally it has such a feeling. It’s amazing.

Trident was much more laid back. It was young people. It wasn’t like the old people who ran Abbey Road. For musicians, Trident was a place to hang out, whereas Abbey Road you only went in there to record.

Trident was much more laid back. It was young people. It wasn’t like the old people who ran Abbey Road. For musicians, Trident was a place to hang out, whereas Abbey Road you only went in there to record.

I engineered “Hey Jude” [by the Beatles] at EMI, and then a couple of days overdubbing at the Trident Studio, because they wanted to record on 8-track. Trident was the first 8-track studio in London. Trident had these Lockwood cabinets with Tannoy speakers. I worked with George Harrison on All Things Must Pass at Trident.

David and I co-produced Aladdin Sane. It was mostly recorded between December 1972 and January 1973 around his Ziggy Stardust tour. David had more confidence vocally. He was successful by then. He felt he could push the envelope a bit more. I think his influences were coming a little more from the modern situation. I think he was influenced by Bryan Ferry, which became very apparent on Pin Ups. But he’s moving more in that direction as music has changed around him; he’s keeping ahead of it slightly. David was recording around touring.

Like most things, we started “Cracked Actor” with bass, drums and guitar. Then I remember we recorded a little more guitar on top. Then David wanted to put the harmonica on it. He went down and started to play but it sounded so weak compared to the track. So, I said, “Let’s try putting it through Ronno’s Marshall amp. Let’s make it really nasty.” That’s when everything started to really come to life. It was so nasty. It all worked. David had this knack for coming up with different background parts for the singers than most people would.

I wish I could do certain things differently on Ziggy. I always like re-visiting things or working on them because it gives me more to do. Specifically with Ziggy, some of the sounds I got I have no idea how I got them. They blew me away. It was, “Wow. How the hell did I do that?” I had forgotten about how we used to have to feed everything through speakers to the orchestra so they could hear it. If it was loud enough for them it was certainly loud enough for the microphone to pick it up.

When we first turned Ziggy in to RCA the label didn’t hear a single. We removed “Around and Around,” a Chuck Berry song, and then David came up with “Star Man.” My favorite on the album is “Moonage Daydream.”

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationWhat a fantastic interview with the Master — Ken Scott. In my opinion, the production aspects of Bowie’s records in this period have as much to do with the greatness of the records as what’s recorded on them. And for that, in my opinion, Ken Scott has never really been given his due as a critical component of these classic records. While Tony Visconti wants to take credit as “Bowie’s Producer,” the truth is he actually only produced Bowie’s early LPs, which, in my opinion could have been much more successful had they not suffered from poor audio production, and then he rejoined Bowie late in his career to produce his last four records, which, at this point in Bowie’s career, all had a strange disjointed musical quality to them to start with (I say this as a fan), with Visconti’s often vague-sounding treatment of the recordings making them even less accessible to all but the most fervent fans.

Hearing Scott’s perspective of how Bowie depended on his producer for so much of the final sound of his records, makes me wonder why Bowie went back to the guy he started with, who had made his early records sound so much more amateur, instead of the guy who Bowie made his best records with. Just imagine how those late career records of Bowie’s might sound with a grounded producer who knew how to make the music really stand up, and Bowie’s vocals stand out, instead of a wash of audio that sounds like it was created from a bunch of tracks put together from separate rooms.