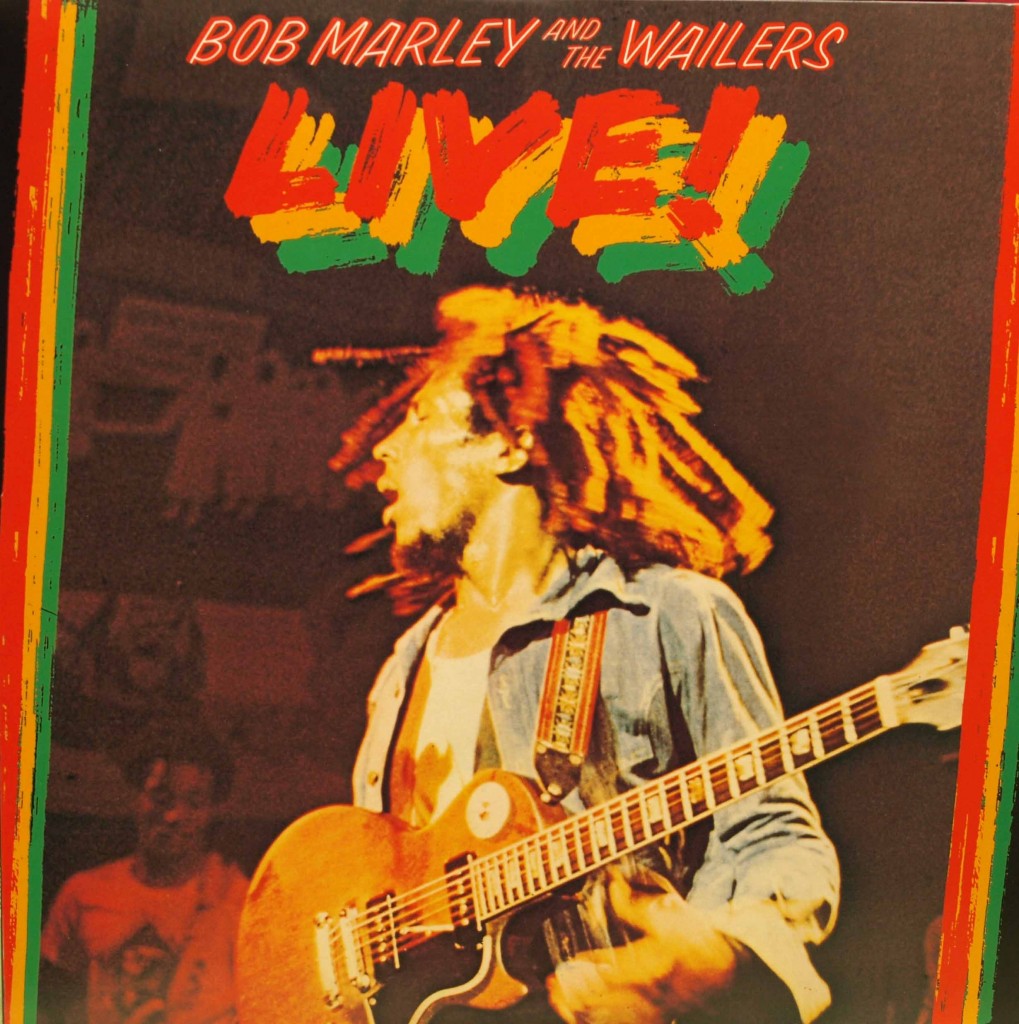

Bob Marley and the Wailers’ ‘Live!’ Album: Reggae Rocks Babylon

by Sam Sutherland Taking the stage of London’s Lyceum Theatre on July 18, 1975, Bob Marley opened his set with a promise of joyful release. “One good thing about music,” he sang, “when it hits, you feel no pain.” For the veteran singer, songwriter and guitarist, the night was further validation that Marley and his band, the Wailers, had breached the rock market with their potent strain of reggae, consolidating its reach beyond the Jamaican diaspora. It was a victory years in the making for both Marley and the music.

Taking the stage of London’s Lyceum Theatre on July 18, 1975, Bob Marley opened his set with a promise of joyful release. “One good thing about music,” he sang, “when it hits, you feel no pain.” For the veteran singer, songwriter and guitarist, the night was further validation that Marley and his band, the Wailers, had breached the rock market with their potent strain of reggae, consolidating its reach beyond the Jamaican diaspora. It was a victory years in the making for both Marley and the music.

Exactly two years earlier, the original Wailers had served notice on American tastemakers that they were a force to be reckoned with by stealing thunder from no less a rocker than Bruce Springsteen, then seven months into his recording career and headlining a four-night run at Max’s Kansas City in Manhattan. As the latest protégé for legendary producer and talent scout John Hammond, Springsteen had the formidable resources of Columbia Records in his corner and a fistful of glowing reviews and favorable “new Dylan” comparisons to make him the man of the moment.

Instead, the once and future “Boss” was eclipsed by the opening act’s explosive set. If the Wailers (not to be confused with the proto-garage band from Tacoma, Washington) were newcomers to Max’s downtown cognoscenti, they weren’t rookies by any standard. Co-founders Peter Tosh (born Winston McIntosh), Bunny Wailer (born Neville Livingston) and Bob Marley had teamed a decade earlier as a vocal trio, conjuring their first ska hit not long after Millie Small introduced the style’s buoyant, uptempo dance rhythms outside Jamaica with “My Boy Lollipop,” a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

By the time they hit the stage at Max’s, the Wailers were a seasoned, self-contained band plying a deeper, more nuanced reggae style that throttled its push-and-pull pulse to a slower, more sensuous pace than its ska and rock steady precursors. Newly signed to Island Records—the British label behind Small’s 1964 hit—the Wailers were being groomed to tap into glimmers of mainstream interest hinted at by isolated hits for Desmond Dekker (1968’s “Israelites”) and Johnny Nash (1972’s “I Can See Clearly Now”), and experiments from the Beatles (1968’s “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”) and Paul Simon (1972’s “Mother and Child Reunion”). Island’s other big bet on reggae’s future, its investment in Perry Henzell’s indie theatrical feature, The Harder They Come, and its definitive soundtrack album, was also courting fans beyond the island that same year.

The two years between the Wailers’ ambush at Max’s and the triumph at London’s Lyceum witnessed upheaval for the band even as their original music further cohered around more explicit social and political themes. Jamaican music had long mixed pleasure with pain, dating back to the mento songs subsumed into ’50s calypso, which mingled sunny romanticism with hints at underclass tribulations. Reggae more pointedly mixed odes to sex and love with violent fables of crime and retribution in Kingston’s shanty-town slums, as well as gospel-tinged hymns of suffering. Patois framed the speech, and for many fans and musicians alike, Rastafarianism, the homegrown, Afro-centric religion created during the 1930s, further geo-located the music on an island where political independence was only recently achieved.

Following the Wailers’ second studio album for Island, Burnin’, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left the band over their discomfort with some concert venues, citing their Rastafarian beliefs. With the original Wailers disbanded, Marley retained the original rhythm section of drummer Carlton Barrett and bassist Aston “Family Man” Barrett and added new members, with the Lyceum lineup featuring Al Anderson (guitar), Tyrone Downie (keyboards) and Alvin “Seeco” Patterson (percussion). In place of the early band’s male vocal frontline, Marley’s lead vocals were supported by the female I-Three trio, including his wife, Rita, Judy Mowatt and Martha Griffiths.

That the reconfigured Marley and the Wailers continued their march toward more spiritual and political themes is clear from the live album’s choice of material. The opening “Trenchtown Rock” celebrates its origin (“give the slum a try…”) and adds its postal code (“Kingston 12”) to confirm Trench Town’s precise location within the city’s St. Andrew Parish, giving its promise of “feel(ing) no pain” visceral impact. The sense of the music’s shanty-town locales and the ongoing threat of social dangers persist across five of the six other songs included.

“Burnin’ and Lootin’,” which gave the final studio album from the Wailers its title, evokes an urban battleground between impoverished Jamaicans and the authorities enforcing Kingston’s nightly curfews. And the societal divide between the impoverished residents of the shanty towns and middle-class Jamaicans living above the poverty line could not be more bluntly defined than by the rumbling discontent of “Them Belly Full (But We Hungry).” Marley’s call for political activism was no less direct and even more concise with “Get Up, Stand Up.”

Prior to the Lyceum show, Marley’s best-known song was “I Shot the Sheriff,” first released by the Wailers in 1973 before Eric Clapton’s 1974 cover version became a breakout international hit. Marley cited his decision to make his target a sheriff instead of a policeman as a practical compromise, admitting, “The government would have made a fuss…but it’s the same idea: justice.” That night another more recent Marley song emerged that would prove more substantial in message and emotion.

On Marley’s first album with the reconstituted Wailers, Natty Dread, “No Woman, No Cry” offered a respite from the sense of menace pervading the set’s vignettes of street-level repression and rebellion. The live Lyceum performance offers audible proof of its power as fans sing the now beloved title refrain, its message of solidarity that much more poignant. Released as a single, this version is definitive, one of his most tender and humane compositions, as well as proof of the spiritual and political commitment underlying his music.

Despite its images of communal sharing, reference to “corn meal porridge,” Marley’s own favorite dish, and a melody reminiscent of other Marley songs of praise and redemption, the piece is credited to Vincent Ford, a friend who ran a Trench Town kitchen that was further subsidized by royalties. That “No Woman, No Cry” was a Marley composition in whole or part has been widely assumed since.

The success enjoyed by Marley and the Wailers wasn’t without its ironies as far as U.S. audiences went. In signing the band to Island, label founder and Wailers producer Chris Blackwell correctly identified their appeal to rock fans at a time when most U.S. and British bands were apolitical. Marley’s Rasta beliefs, including his sacramental reverence for ganja, coiled dreadlocks and recurrent Jamaican color motifs, could be trivialized by fans too stoned or lazy to decode his lyrics.

Live! was released by Island Records on December 5, 1975. One year later, the reality of his political commitment, and the risk it carried as he became a global icon, were brought to Marley’s Kingston doorstep on Dec. 3, 1976, when unknown gunmen assaulted his Hope Road home two days before he would headline the free “Smile Jamaica” concert organized to calm tensions between the country’s two warring political parties. Marley, his wife Rita, and manager Don Taylor were all wounded in the attack, but Marley and the Wailers still played the date.

[The album is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Bonus Video: Although identified as Bob Marley and the Wailers, this 1973 clip features the original lineup with co-founders Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer sharing the front line with Marley.

Related: What were the best albums of 1975?

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.