Bob Dylan: Reflections on His Early Days by Those Who Knew Him

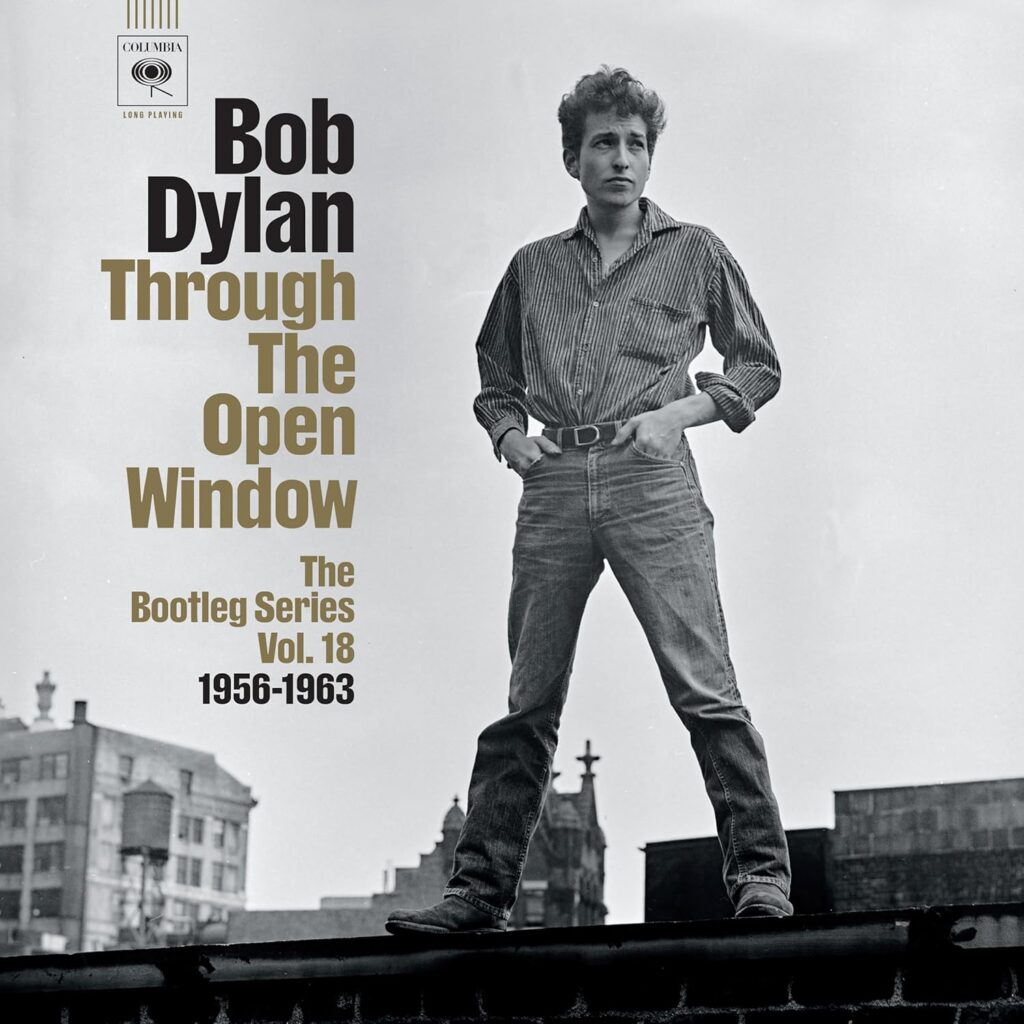

by Harvey KubernikBob Dylan’s Bootleg Series Volume 18: Through The Open Window, 1956-1963, the latest in Legacy Recordings’ ongoing archival series, trains a spotlight on the earliest days of its subject’s recording career (and even before he ever signed a contract). The 2025 collection tells the story of the emergence and maturation of the young Dylan as a songwriter and performer, born in May 1941, from Minnesota to the Greenwich Village bohemia of the early 1960s. It includes rare Columbia Records outtakes, recordings made at club dates, in tiny informal gatherings, in friends’ apartments, and at jam sessions in long-gone musicians’ hangouts.

[The Deluxe edition on 8-CDs—featuring 139 tracks including 48 never-before released performances, as well as 38 “super-rare” cuts—is available in the U.S./worldwide here and in the U.K. here; and as a highlights edition on 4-LPs or 2-CDs, available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here. All three editions are available in Canada here.]

During 1975-2025, music journalist Harvey Kubernik asked some of his nearly 3,000 interview subjects about their memories of Dylan during 1961-1963. Among the interview subjects are fellow musicians who worked with Dylan and may have covered his catalog, those who simply encountered him in that seminal period and a filmmaker who documented him on screen.

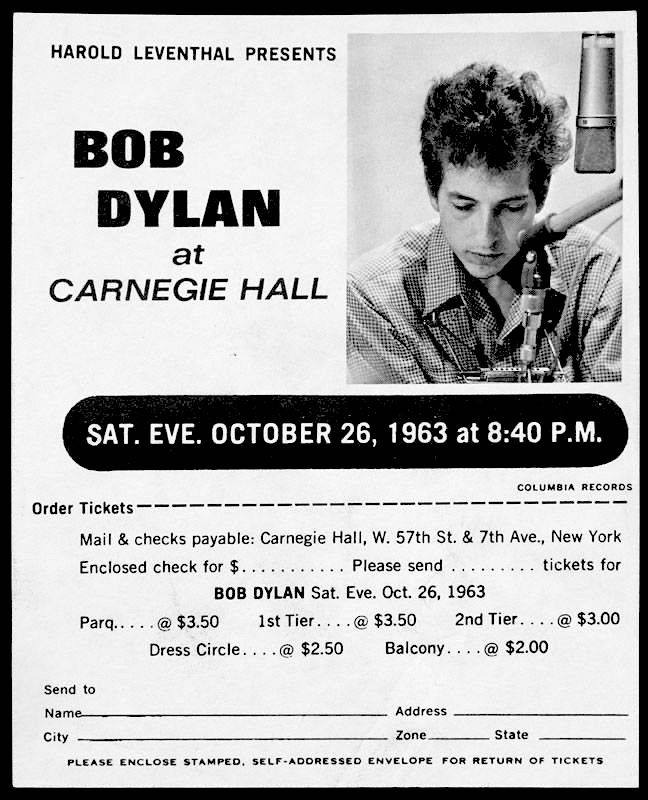

Billy James (Columbia Records publicist): I [first] saw Bob Dylan in the Village. Then [as publicist for his label], in 1961 I taped an interview with him for the company and prepared his first biography. I worked for Columbia as a talent scout as well. I went to Bob’s solo acoustic recording sessions and continued as a writer for the Columbia label. Regarding the early Dylan that I met, I wrote an article for the weekly edition of Variety when I worked at Columbia Records. My headline ran, “Folk Fans Find a James Dean.”

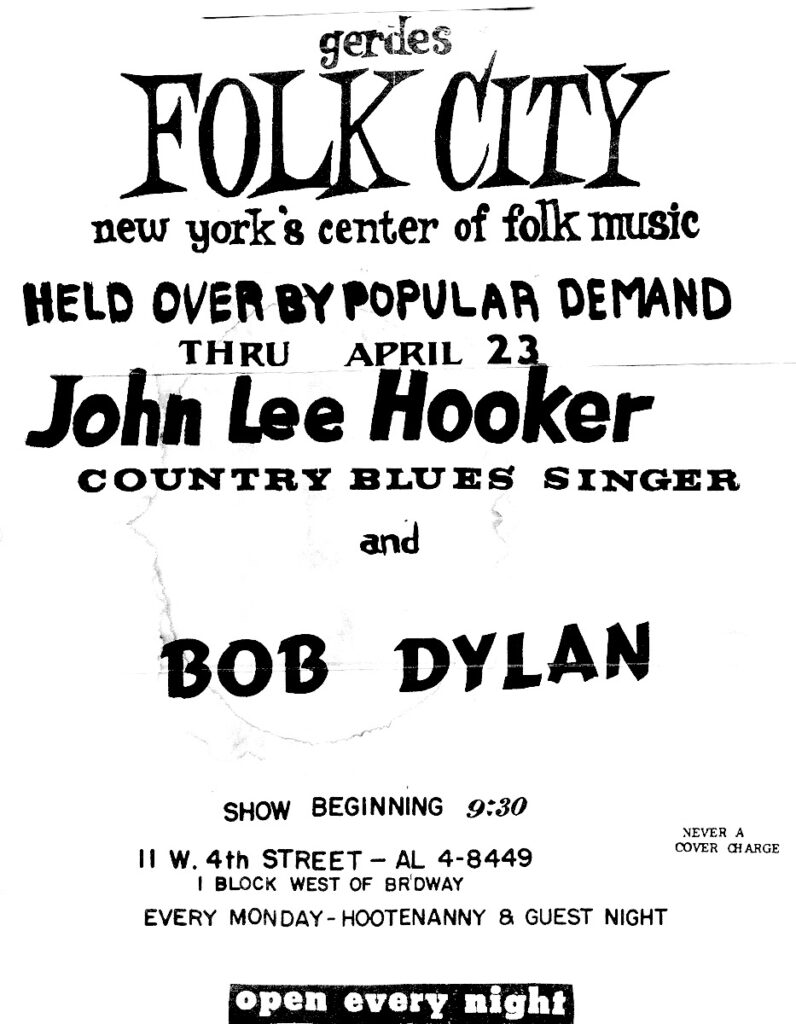

Chip Monck (lighting designer, emcee at Woodstock): I knew Dylan and saw him at the Gaslight [club in the Village]. Dylan was playing a set there in probably 1961, and [his manager] Albert Grossman came in on his usual talent hunt. Dylan does three or four songs, and the kitchen door slams. And all of a sudden, those tapes become Bob Dylan: Live at the Gaslight 1962, with no credit to the engineer Richard Alderson. It was a single-microphone record. Then, after that, we go to the Kettle of Fish, which is upstairs, and while having a drink, I introduce myself. “That was great. I really like that. That was fun. Sorry about the door slamming.”

Dylan was extremely new and different and had already been turned down to play the Village Gate because Art D’Lugoff, the owner, already had Jack Elliot. Art was one of the most important people in Greenwich Village on so many levels.

Then Dylan and I met again on the street. He said, “You got a typewriter, don’t you?” “Yes, I do.” “I want to use it.” “OK. Here are the keys. I’ll show you where I live. And by the way, it’s right next door to the Village Gate. So, if there is anything you want to listen to or want to eat or have something to drink you can just walk through the door with this key and you are in the Gate.” “OK.”

Every now and then I’d come back into the apartment after my two shows at the Gate and he’d be there plucking away. “Can I see it?” “Yeah.” “Don’t you think it would be better if it was phrased like…” “I don’t need a f**kin’ co-writer! Nor do I need to pay royalties to your typewriter. You can read it but just keep your f**kin’ mouth shut.” “OK. Would you like to have something to eat, Mr. Dylan?” (laughs).

That was about the extent of it. Every now and then it would go missing and then it would come back and have a complete, new typewriter Correcto-type ribbon in it. I figured this is a co-owned typewriter and fine with me. I don’t have to type his words. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Hollis Brown” were two I remember. “Hard Rain” was the primary. And what I’d do is just take out the paper in the wastebasket at end of the night, iron it flat, put it in a folder, which was unfortunately lost when my first wife Barbara sold our Bridgehampton, Long Island, house. Some contractor probably has it in his files.

At the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 I saw him do “Hard Rain” with the guitar. I only saw it previously as the uncompleted number.

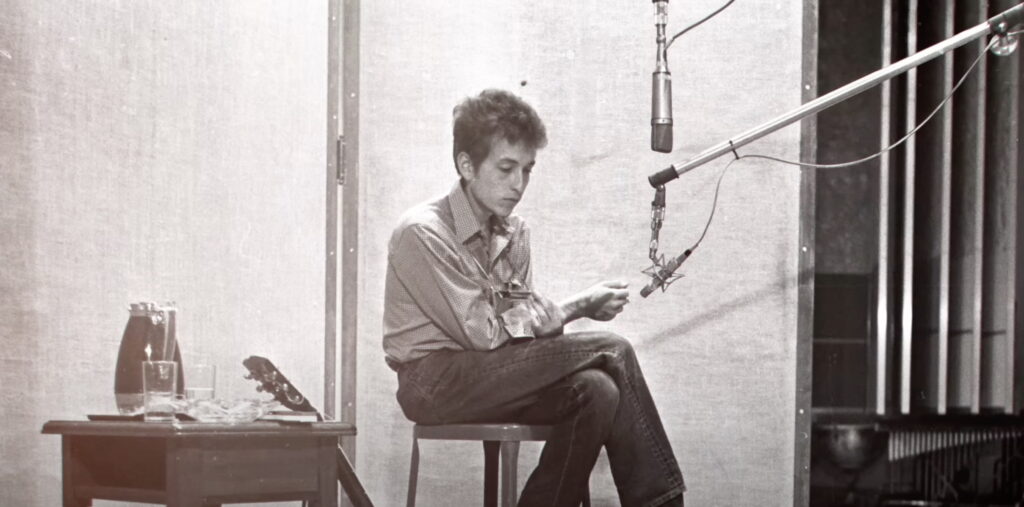

Fred Catero (Columbia Records engineer): I started in 1962 as a mixing engineer. Roy Halee did most of the rock stuff. John Hammond [who signed Dylan to the label] introduced me to Dylan. I worked with [producer] Tom Wilson on Dylan [1964 and 1965] sessions.

I knew the rooms and where the best place was for piano or bass or the singer. I used two Neumann mics: one for the guitar, which I aimed at an angle down, so it’s not picking up too much voice, and then the vocal mic, not in front of him, almost where the same mic is for the guitar is facing upward. ’Cause they tend to look down anyway as they play.

Allen Ginsberg (poet): Dylan said that Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues had inspired him to be a poet. That was his poetic inspiration. In fact, I remember when Kerouac was asked on the William F. Buckley TV show [Firing Line] in the ’60s, what Beat Generation meant, Kerouac said, “Sympathetic.”

I remember the first moment I saw Dylan. It was a concert with Happy Traum that I went to in Greenwich Village. I suddenly started to write my own lyrics, instead of [William] Blake’s. Dylan’s words were so beautiful. The first time I heard them I wept. I had come back from India, and Charlie Plymell, a poet I liked a lot in Bolinas [California], at a party, played me Dylan singing “Masters of War” from Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and I actually burst into tears. It was a sense that the torch had been passed to another generation.

Related: Dylan has announced plans for his 2026 tour

Johnny Cash (country legend): I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I was in Las Vegas in ’63 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back, and we developed a correspondence. We finally met at Newport in 1964. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He’s unique and original.

Jackie DeShannon (singer-songwriter): In 1963, I was invited by Peter, Paul and Mary to see Bob Dylan at his first concert appearance at Town Hall in New York. Immediately, I knew how important he would be. When I returned to Los Angeles, I tried to convince the [Liberty] record label to let me do an entire album of his songs. No one at the company listened and understood.

I did eventually record a few of his tunes: “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right” and “Walkin’ Down the Line” on a Liberty album in the early ’60s.

Robby Krieger (The Doors’ guitarist): I saw Dylan perform in 1963. I was in high school in Menlo Park, near San Francisco. There were some guys there from Boston and New York in the dormitory with me and they were into Bob Dylan. I had never heard him before. They had his debut LP. So, they played the first album and I got totally into him.

On Dylan’s first album I really liked his guitar playing. I thought he was a great f**kin’ acoustic player. He did some stuff that was pretty damn good. And his harmonica work. I had never heard anyone play harmonica like that. Not a blues harmonica player sucking in the notes. I was amazed he could do all that stuff and sing at the same time.

Then, he came to Berkeley for the first time and we saw him at the Community Theater. It was a good experience. He had the buckskin jacket. I bought into the whole thing, basically. I later bought a harmonica rack holder. When I saw him live, I sort of realized at the time there were some interesting and unique tunings on stage. I thought he was pretty cool at that first concert, and then the week after that we saw Joan Baez play at Stanford University.

Andrew Loog Oldham (Rolling Stones manager): I worked as a press agent for the Beatles, Chris Montez, Bob Dylan and the Little Richard/Sam Cooke/Jet Harris 1962 tour before I met the Rolling Stones in 1963.

In 1963, I managed to score some press for the still-unknown-folk singer in England. I was doing PR in January ’63 and bumped into manager Albert Grossman at the Cumberland Hotel, Marble Arch. His client, Bob Dylan, was in London to play a minor role in a BBC2 television drama, Madhouse on Castle Street. He would eventually perform two songs: “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Ballad of a Gliding Swan.” [It was broadcast on January 13, 1963]. It was written by Evan Jones and the director was Philip Saville. I got a “fiver” for 10 days of work. I managed to get Dylan into Melody Maker. Thanks to Max Jones or Jack Hutton. They were doing me a favor. Nobody else cared.

Dylan and Grossman were very happy together. They acted like they knew something we didn’t know yet. There was this conspiratorial thing that was so powerful; you knew it had to work.

Murray Lerner (documentary film director): The words just fell on his music. I knew that when I saw him walk in a room at a party around 1962. He came in and pulled out his guitar, played a few songs about New York, packed it up and split. He intrigued me. I felt the wondrous quality of his imagination took us like Alice to a new world on the other side of the mirror. I felt to break that would be bad.

Dylan’s songs and his ideas were so powerful that my thesis, or premise [in my film The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival], was that once I got you involved in him and you were also seeing a change in his imagination going in his music that you wouldn’t want to leave it. Either I pulled you into it or I didn’t. If you weren’t pulled into his music and took this journey with him then you’re not going to like the film. Nothing you say is gonna make you like it more.

Bette Midler (singer, actress): I came to New York to meet Dylan. I was 19 when I first hit New York and the first thing I did was go down to the Village and look for him. Those first albums of his completely blew my mind. I had a very hip girlfriend, and we used to go to her house and listen to Dylan and Joan Baez. I even went out and bought a guitar so that I could accompany myself on “Blowin’ in the Wind.” I spent a lot of time lookin’ for him. He didn’t let me down at all.

Anthony Scaduto (Dylan biographer): As a police reporter writing for The New York Post [on organized crime and the Mafia], I got turned onto rock because I was assigned to cover the Brooklyn Fox Theatre, where the kids were ripping up the seats over Little Richard. Rock and roll hit, and I got into it a great deal.

Then Bob Dylan came into the Village. Originally, I hated him…but soon my sentiments toward the man and his music became quite positive. I felt that rock was, and still is, an important part of our culture. I felt there was a so-called message there, and it was saying something to Western society. My editor suggested I write a book on rock, since Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia [1969] was selling quite successfully. I said, “Dylan, of course,” since I had always wanted to do at least a magazine piece on him.

Dylan was a very hidden character. No one really knew who Bob Dylan was, so I handled him in a very straight biographical manner. Dylan reviewed a work-in-progress manuscript of [Bob Dylan: A Biography, 1972], and was interviewed. “You’ve done a good book on me. I want to make it even better.” He later said, “I like the book. That’s the weird thing about it.”

I write with a lot of compassion for Bob Dylan. I respect him as a person and an artist. The people surrounding Dylan always felt that he was a very fragile person. It was as if he had to be protected. It wasn’t until a few years later that Joan Baez, Dave Van Ronk and Suze Rotolo would talk freely and honestly about him.

Dylan only wanted to be the next Elvis. There was this intense pain that forced him to write certain things that came out of the air. A poet feels his own persona, his place in the world, and the screwed-up condition in that world.

If you are going to get into a superstar level, you have got to be hard. In the beginning, Dylan had the bodyguards, the Albert Grossmans. You’re an idol, and it’s the kind of thing they put you on the crucifix for. You have to be hard and be protected, or it’s going to destroy you. [A Scaduto book on Dylan is available here.]

[Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.]

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.