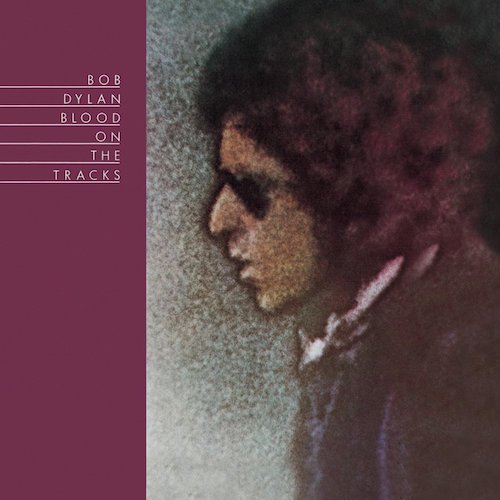

By the time of 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, Bob Dylan had moved through a succession of distinct musical personae. Beginning his career as a Woody Guthrie acolyte, Dylan soon established his own voice, singing and writing original folk protest songs. After famously “going electric,” Dylan bent the rock aesthetic toward his own musical ends, and soon crafted the sublime double-LP Blonde on Blonde (1966).

By the time of 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, Bob Dylan had moved through a succession of distinct musical personae. Beginning his career as a Woody Guthrie acolyte, Dylan soon established his own voice, singing and writing original folk protest songs. After famously “going electric,” Dylan bent the rock aesthetic toward his own musical ends, and soon crafted the sublime double-LP Blonde on Blonde (1966).

From there, Dylan shifted radically toward a back-to-the-roots vibe with 1967’s John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline in 1969. His commercial and critical fortunes took a hit as the quality of his work seemed to flag somewhat with a succession of albums in the early 1970s. But in 1975 he roared back with his 15th album of new material, one that would come to be recognized among his finest: Blood on the Tracks.

Whereas during Dylan’s folk-protest period he wrote lyrics that commented (if obliquely) upon social concerns, the collection of songs that make up Blood on the Tracks is decidedly inward-looking and personal. While his writing continues to be filled with metaphors and obscure turns of phrase, with these songs Dylan is often chronicling the disintegration of his marriage (he and Sara Lownds Dylan would divorce in 1977).

Watch a live performance of “Tangled Up in Blue” from Dylan’s Renaldo and Clara film

True to his idiosyncratic nature, Dylan approached the sessions for Blood on the Tracks in an unorthodox manner. Having recently returned to Columbia Records after a disappointing run of releases for David Geffen’s Asylum Records, he enjoyed free rein in the making of the album. Sessions took place in September 1974 in New York City at the former Studio A in which Dylan cut much of his early work. Working with members of little-known band Deliverance, he began recording the new songs. Two days in, he fired most of the group and brought in other players including Buddy Cage of the New Riders of the Purple Sage (steel guitar) and organist Paul Griffin, who’d played on“Like a Rolling Stone.” In less than two weeks, the album was seemingly finished.

Related: Another album that made 1975 special, from a guy once called “the new Bob Dylan”

But after previewing the stark, stripped-down recordings to select friends and family, Dylan made a decision to overhaul the album. Returning to his native Minnesota in late December, Dylan cut completely new versions of five of the 10 songs that would ultimately appear on Blood on the Tracks. Notably, when the album was released a mere three weeks later (January 20, 1975), the sleeve credits included no mention of the half-dozen musicians who took part in the December sessions. Despite the plethora of subsequent archival Dylan releases, four of the five abandoned recordings from the New York City sessions remain unreleased.

With a sound that recalls his Blonde on Blonde period, Dylan opens the album with “Tangled Up in Blue.” A story song, the tune is peppered with some of the composer’s cleverest and wryest phrases (one example: “I helped her out of a jam I guess/but I used a little too much force”). At once, Dylan seems to be telling a straightforward story and cloaking it in enough mystery to make the specifics unclear. In that way, “Tangled Up in Blue” is a musical cousin to the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood,” a John Lennon song clearly informed by none other than Dylan himself. The song’s full-band arrangement is simple yet effective, and Bill Berg’s uncredited brush work on the drums is superb.

“Simple Twist of Fate” is a song from the New York sessions. It’s essentially Dylan’s voice and guitar (and a harmonica solo) with some wonderfully subtle bass guitar from Tony Brown. The song finds Dylan turning in one of his most expressive vocal performances. Its chorus-less structure allows the verses to roll out one after the other, like short chapters of a novella. The repeated title phrase ties each verse together with the others.

Coming after those two tracks, “You’re a Big Girl Now” sounds at first as if it’s from a different album. The instrumental interplay is much more layered than the previous tunes. As the song unfolds, occasional bum notes can be heard, but they don’t detract from the song. Dylan’s still in fine voice on this Minneapolis recording as he sings directly of love and its aftermath. The heart-rending song is among his most lyrically direct.

Listen to an earlier take of the song

Another Minneapolis recording, “Idiot Wind,” is Bob Dylan at his nastiest. At nearly eight minutes, “Idiot Wind” is the second-longest song on Blood on the Tracks. Here Dylan has returned to his oblique lyrical style. But there’s no mistaking his feelings when he sings in the song’s chorus, “You’re an idiot, babe/It’s a wonder that you still know how to breathe.” The full-band instrumental work (with prominent organ) conveys restrained emotion, and serves to heighten the lyrical intensity.

Dylan lightens the mood significantly with a tune that harkens back to some of his earliest work. “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” is a highly appealing campfire-style tune. Vocal, guitar and bass (and, once again, a harmonica solo) are all that are heard on the song; Dylan’s voice is up-front, and unlike many of the songs on Blood on the Tracks, the tune features a bridge or “middle eight,” presented twice for good measure. “Lonesome” is Blood on the Tracks at its most upbeat.

A languid blues, “Meet Me in the Morning,” hints at the musical direction Dylan would explore on subsequent albums like Desire and Hard Rain. Surprisingly, it’s this, a New York City recording, that displays the most “produced” sound on all of Blood on the Tracks, with at least three guitars, electric bass, drums and other instruments, all blended seamlessly. A tasty electric guitar solo is among the song’s many highlights.

A bouncy country blues, “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” is as epic as its title suggests. At nearly nine minutes, it’s the longest piece on Blood on the Tracks. As long as it is, bootlegged versions exist featuring even more verses. “Lily” would become fodder for the legion of Dylanologists to analyze; its allegorical lyrics tell a story of sorts, but it’s ultimately left up to the listener to discern what it’s all about.

The fifth of the Minneapolis recordings on Blood on the Tracks, “If You See Her, Say Hello,” features a lengthy instrumental introduction. A deep sense of melancholy and resignation pervades the song, and Dylan adopts a direct lyrical approach, explicitly mentioning his separation from his wife Sara.

Watch the video for “If You See Her Say Hello” (Take 1) featuring Dylan’s handwritten lyrics

Related: 10 blatant Bob Dylan imitations

From the New York sessions, “Shelter from the Storm” suffers slightly from a sameness in arrangement, one that vindicates Dylan’s decision to re-cut half of the album’s tracks. But the song itself is as fine as anything he’s written. Dylan’s vocal alternates deftly between a near-whisper (one that all but compels the listener to lean in and pay attention) and shouted phrases that emphasize certain lyrics. Structurally it’s quite close to “Simple Twist of Fate.”

Blood on the Tracks closes with “Buckets of Rain,” another New York City recording. Here Dylan adopts his most nasal vocal tone, and the guitar texture is notably sharp and brittle. Musically he’s in folk troubadour mode, but lyrically he’s once again singing about love, albeit in a most oblique fashion.

On its first few pressings, Blood on the Tracks’ back cover featured a dense and impenetrable essay from Pete Hamill, plus an illustration that seems to bear no relation to the music nor Hamill’s verbiage. On its release, Blood on the Tracks proved to be Dylan’s most commercially successful album in years, topping the album charts in the U.S., and scoring well overseas. The sole single from the LP, “Tangled Up in Blue,” even managed to crack Billboard’s Top 40 chart in 1975, Dylan’s first time on that chart since 1973’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.” And while critical reception would initially be mixed, Blood on the Tracks has eventually taken its rightful place as one of the very best collections of music from Bob Dylan.

Blood on the Tracks and other Dylan recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

7 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationAs far as critical reception: I remember that when Planet Waves initially came out in 1973, the critics all raved about it. Then when Blood on the Tracks was released, all the critics raved about it while saying how much they had hated Planet Waves.

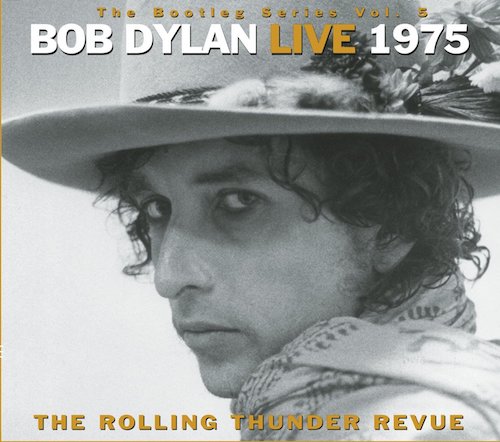

This is one of my all time favorite albums. I recommend that fans watch the “Rolling Thunder Review” movie which occurred during this same period. Thank you for featuring this great album by this important and influential (and enjoyable) artist.

I totally agree. The Netflix movie helped me ‘rediscover’ the genius that is Dylan. It doesn’t get any better than Blood on the Tracks, Desire, and and Live 1975.

Hahaha, Pick your favorite Dylan album, right.

Which four from NYC remain unreleased?

I thought they all were.

I could be wrong but I think Idiot Wind is the one that was released. A radically different vocal — gentle, not angry. And far inferior to the LP version.

CREEM Magazine — whose hallmark approach was irreverence — had one of the less than stellar reviews. It began: “Bob Dylan is pussywhipped.”

That opening, however, is not as famous as Rolling Stone’s *Self-Portrait review, which began: “What is this sh*t?”