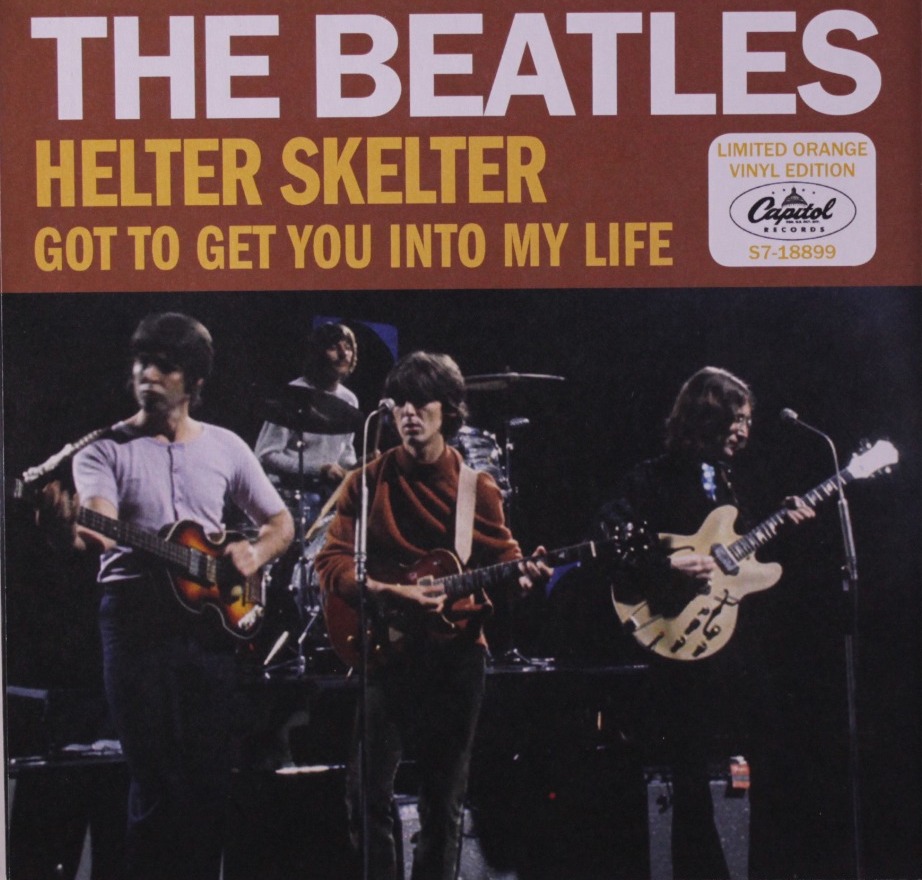

Gotta Bludgeon: The Delightfully Punishing, Hell-for-Leather Second Take of The Beatles’ ‘Helter Skelter’

by Colin Fleming The idea of the Beatles as amped-up—figuratively and literally—sonic bludgeoners is at distinct, defiant odds with their well-earned renown as unrivaled melodists.

The idea of the Beatles as amped-up—figuratively and literally—sonic bludgeoners is at distinct, defiant odds with their well-earned renown as unrivaled melodists.

They could rock and rock hard—“I’m Down,” “Yer Blues” and the long medley on Abbey Road being but a few examples—but they didn’t pound you upside the head in the manner of Black Sabbath in the not-so-distant future, or AC/DC later on. Save for one time, and some extended times within that time, in a manner of speaking.

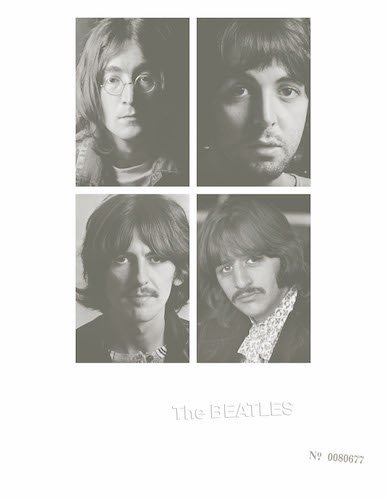

We’re talking about “Helter Skelter,” the infamous White Album cut whose infamy stems form Charles Manson interpreting the song as an apocalyptic call to mayhem and murder and factor in his horrific crimes, despite the bulk of the actual subject matter pertaining to a child’s slide at a carnival. The White Album doubled as The Beatles’ open invitation to themselves to experiment as much as they pleased and pursue every last caprice so long as there was a song in the end. Or a collage. A sketch. The results from a juicy experiment. Or a sound to blow your door open.

Paul McCartney had encountered a quote from the Who’s Pete Townshend in which the latter—in McCartney’s recollection, anyway—had gone on about the Who’s latest single as the loudest and dirtiest record ever. As the Beatle who was always the most competitive, McCartney decided he’d write a song even louder that would out-dirty the Who.

What’s ironic about this is that it sounds like Townshend was talking about some crude, lumbering number, when the song in question was “I Can See for Miles,” a sleek beast of taut power and muscled rhythm—sinister in spots (the gunshot drum opening, the guitar solo), yes, but a long way from scuzzy.

Every bit as strange is the number of people over the decades since who have stumped for “Helter Skelter” as this trailblazing attempt at heavy metal, when many earlier examples were to be found in the middle of the decade, thanks to the Yardbirds, Kinks and a horde of American garage acts (the Sonics being the most obvious), plus there was Howlin’ Wolf and his guitarist buddy Hubert Sumlin in the 1950s shredding with max volume.

Critics often don’t like “Helter Skelter,” whereas fans usually do. It’s intentionally contrived and parodic—and meta that way—but there’s appeal in how it comes at you in a repetitively stylized, all-but-looped, wave.

For all of the bombast, the lyrics—“Will you, won’t you”—draw on singsong lines of whimsy from the Mock Turtle in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland—and have a cyclical, longitudinal flow, appropriately enough for a song that’s about going down a slide and racing back up to go down again. There’s also this decadent, filthy oil stain of a guitar solo, with a tone unlike any other guitar part in the Beatles’ canon.

If “Helter Skelter” isn’t that different from a lot of what was happening in rock in 1968, it was still different for the Beatles. As for the White Album: when you’re doing this grand tour of musical styles, something needs to represent heavy metal, and “Helter Skelter” carried the charred flag.

The song also gave rise to a million daydreams about what the extended rehearsal versions must have sounded like, and thanks to the super deluxe edition of the White Album, we can pound our ears into submission—or sonic addiction—with the 12-and-a-half-minute second take from what was the second session on July 18.

The first session—which ran from 2:30 in the afternoon to 9:30—saw the Beatles complete John Lennon’s “Cry Baby Cry,” and having done one track of a given type, they turned around an hour later and started work on what passes for its opposite (though with whimsical overlap in the lyrics), keeping at it until 3:30 in the morning. This was the Beatles and this was the White Album, and both were marked with that “can do” spirit. If there was a boundary, it existed to be detonated and for band, song and album to take up space in new lands.

There are three rehearsal takes of “Helter Skelter,” with the first lasting 10’40” and the third an eye-popping 27’11”. Is this the Beatles or the Grateful Dead here? But even the Dead weren’t going off for a half hour in the studio on a single number. A considerably edited-down version of the second take was included on Anthology 3. George Martin had to be lobbied to put it on the set, not seeing what the big deal was. After all, this was a jam, a zany expedition to scratch a heavy metal itch, or perhaps get something out of the system. To him, the value—if there was any—was its novelty, and, duly nudged, the reputation of these rehearsal versions.

But not only can you sit down and listen to the second take of “Helter Skelter” and feel rewarded for doing so, the thing is addictive. Hear it once, you want to hear it again, and it’s long enough that the song is like some heavy metal party in EP form, but without breaks.

Right from the song’s beginning, we’re tipped off that things are about to turn a bit loud so duck and cover, if you’re the type. The studio equipment squeaks, stumbles, distorts, overloaded from the initial notes. You question whether the speakers are going to survive or get fried like the laser-blasted soldiers in Orson Welles’ “The War of the Worlds.”

Related: Read the backstory of a very different White Album song, “Julia”

John Lennon plays bass, with McCartney on co-lead guitar—the bedrock riffing with the strings on his instrument seemingly coming loose is him—as George Harrison tosses in menacing licks in conjunction with the synodic throb of the beyond-this-world juggernaut. It’s akin to jamming with H.P. Lovecraft. Close your eyes and it’s not hard to picture George Martin in the control booth, head in hands, thinking, “What on earth are we doing tonight? These bloody guys.” (Martin would be on holiday for the September 9 session when the Beatles returned to “Helter Skelter” and cut the album iteration, with Chris Thomas, Martin’s 21-year-old assistant, producing.)

The title phrase is rhymed with “hell for leather,” an idea that maybe they should have kept for the official version, and those three words seem to sum up what’s happening here. Lennon’s playing is similar to the Who’s John Entwistle’s on the Live at Leeds version of “Magic Bus,” that ad infinitum thudding. Entwistle hated that bass part, and this show is hardly Lennon’s, but minus his minimalist approach to this instrument he rarely played, none of the rest of it happens.

Listen to the nearly half-hour take…

Anyone who loves rock and roll loves its illicit moments, that feeling that we’re in on something “bad” but good. You get it with early, hip-shaking Elvis, the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie,” Jimi Hendrix’s first album, the Doors’ “The End,” the Sex Pistols’ first few singles, the Who’s “My Generation,” the Beatles’ own “A Day in the Life” and Lennon’s declaration—courtesy of McCartney’s line—that he’d love to turn us on. And you certainly get it with this second take of “Helter Skelter.”

Precedent did exist, though who knows if the minds of any of the Beatles were flashing back to the October 8, 1964, session when McCartney screamed his head off—as Harrison fired away on guitar—with a six-and-a-half-minute version of take five of “She’s a Woman.” A half-dozen-plus minutes in 1964 is surely equal to double that in 1968. And if you don’t think “She’s a Woman” has a heavy metal streak, take another listen.

The Beatles were precise artists—they took the time to get everything right—but they also loved cutting wild and free, which was part of their process at times. On the stages of Hamburg, that wildness took precedent, with the Beatles learning that the same energy could power precision.

Listen to the album version

Those stages were always a part of their aesthetic, their gamesmanship, courage to try what others normally wouldn’t, and not to sweat failure, which only meant you could try again and with the same song often enough, be that in the writing or the recording.

And while it’s not an adjective that suits the sound of this second take of “Helter Skelter,” that’s still a lovely way to be. This beast rocks, only slowly, oozingly, achingly. It bodies you and surges through you, until you find yourself moving with it. Get to the end and before too long it’s back to the top for the long ride, which makes for a bludgeoning—but pleasing—amount of sense, and even more fun.

Watch McCartney perform “Helter Skelter” with Steven Tyler in 2019

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.