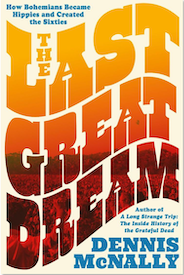

How ’60s Hippies Came to Be: Dennis McNally Talks About His New Book

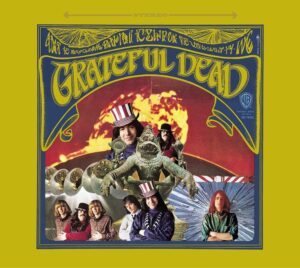

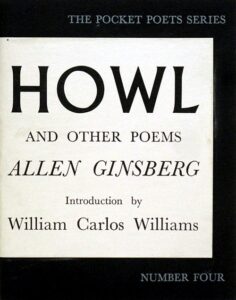

by Jeff Tamarkin Now that we’ve got enough distance from the 1960s to put that decade’s cultural upheavals into perspective, we can ask two pointed questions: How did we get there and what has been the impact of the ’60s since? In his new book, The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties (DaCapo Press), Dennis McNally, the New York Times bestselling author of A Long Strange Trip and longtime publicist for the Grateful Dead, explores the social history of everything that led up to the 1960s counterculture, touching down on specific, crucial events and the people who made it happen, from Beat-era poets and writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac to all of the great rock bands of the era. [The book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Now that we’ve got enough distance from the 1960s to put that decade’s cultural upheavals into perspective, we can ask two pointed questions: How did we get there and what has been the impact of the ’60s since? In his new book, The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties (DaCapo Press), Dennis McNally, the New York Times bestselling author of A Long Strange Trip and longtime publicist for the Grateful Dead, explores the social history of everything that led up to the 1960s counterculture, touching down on specific, crucial events and the people who made it happen, from Beat-era poets and writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac to all of the great rock bands of the era. [The book is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

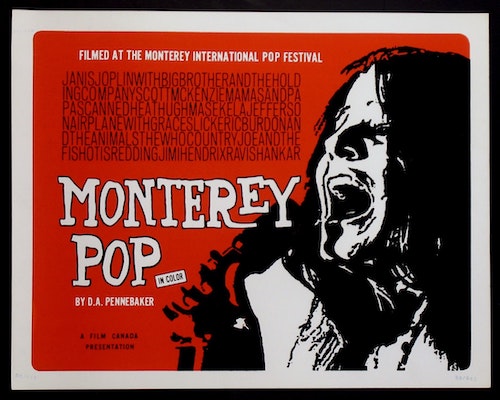

From a press release: “Our story begins with the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance, peaks with the Human Be-in in Golden Gate Park, and ends with the Monterey Pop Festival that introduced Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin to the world. As only he can, McNally ties everything together—San Francisco, New York City and London—into a gripping narrative with a cast of countless visionaries, exploring several micro-histories in the process: Beat poetry, visual arts, underground publishing, electronic/contemporary compositional music, experimental theater, psychedelics and more.”

Best Classic Bands spoke with McNally about The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties.

Best Classic Bands: What is a bohemian, what is a hippie, how are they similar and how do they differ? And why did you choose the word bohemians in the subtitle rather than the Beats?

Dennis McNally: I chose bohemian in the subtitle because it precedes the Beat scene, which is a very specific group of people at a specific time and place (or at least it begins there). By my definition, a bohemian is a person who consciously rejects major parts of the American identity—materialism and conventional morals and social life—to live a life devoted to free-thinking, art and love and the life of the spirit. Thus, Thoreau would be a bohemian despite having no sexual life, nor did he drink; he did free-think and devoted his life to challenging the conventional thought of his era. Hippies followed the same path, but based it more on LSD and rock and roll.

What is the “Last Great Dream” of the title and what makes it so great?

The dream of the Haight [San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, ground zero for the hippies in the ’60s—ed.] was peace, freedom and a more harmonious world. That is a seriously great dream, and various aspects of current culture—not just the political atmosphere, which is directly opposed to such a vision—but technology. The Haight emerged under the radar, but with the current 24/7 digital world, it’s almost impossible for a social gathering to be under the radar. Which is why I chose the word “Last.”

Was there a single turning point when bohemian gave way to hippie, and if so what was it—and why did it happen that way?

The ultimate turning point that catalyzed “hippie” as opposed to bohemian was the introduction of large amounts of LSD made by Owsley Stanley in spring 1965. The values did not change; they were reinforced by the ultimate lesson of LSD, which was that the world was a great deal more complex than conventional society liked to assume.

What made you want to write this book and how does it relate to your previous ones, especially your work on Jack Kerouac and the Grateful Dead?

I started with Kerouac, which meant the history of the ’40s and ’50s. The guy who encouraged me to do it was a Dead Head, and I became one too. By the time I was well into the Kerouac book, I’d noticed the links—Dean Moriarty in On the Road became “Cowboy Neal at the wheel” with the Merry Pranksters [writer Ken Kesey and his associates—ed.]. Turned out Jerry Garcia had picked up on On the Road as his bible at the age of 16, and he made me welcome. Then On Highway 61 [McNally’s 2014 book On Highway 61: Music, Race and the Evolution of Cultural Freedom—ed.] was the background going back into the 1850s, with the trigger that pushed white kids out of conventional culture, which was mostly Black music.

In 2016 I was asked by the California Historical Society to curate a photo show about the “Summer of Love,” and after a while I realized that no one had ever written about where hippie and the Haight came from…and started researching.

Speaking of which, in your own work as publicist for the Dead, you lived in the heart of hippie. As you mentioned, Jerry, in particular, was greatly influenced by Kerouac. What did he find in Kerouac and the Beats that found its way into the Grateful Dead’s orbit?

Kerouac was Jerry’s mentor, and it meant that he was concerned with his music and with the people in front of him…not bucks. He and [songwriting partner Robert] Hunter were the leaders in that regard, and the way he put it was “serve the music.” And they did.

Related: 13 books that all hippies owned

What elements contribute to a segment of society breaking away from the mainstream and creating an alternative way of life? And how do these movements develop certain identifying (and sometimes cliched) hallmarks?

There’s always a variant culture. Freedom in the U.S. has often meant the freedom to make as much money as possible. But there’s always been those who followed their own path. In the 1960s, a considerable group of avant-garde artists gathered in San Francisco and settled in the Haight. LSD was the uniting factor—a physical/sensual way to see that the mainstream description of reality was incomplete. The story of how it happened would include the whole book. As to hallmarks, that’s so variable it’s hard to say why they happen, only that they happened—just for example, the bell bottoms popularized by Cher in “I Got You Babe.”

Bohemian culture and hippie culture had different ideas about art, politics, literature, fashion, music, drugs, etc., yet at the same time there were similar motivations. What determines the characteristics of a movement such as these?

The characteristics arise out of the lived experience of the people in the culture. LSD certainly encouraged a more colorful set of clothing than had the anti-materialist minimalism/darkness of Beat threads.

What fascinates you about countercultural movements and the people who create and lead them?

I was in the backwoods of Maine when “hippie” became a part of the national conversation, and then in way, way upstate New York. So my best guess is that I felt I missed the interesting stuff, and have spent the past 50 years researching what I missed.

Although the book touches on many topics, music is integral to both periods, particularly (but not exclusively) jazz in the Beat era and rock for the hippies. Why do you feel music plays such a central role in countercultural movements and what is it about those genres that so perfectly represented, and drove, the people who were at the heart of those movements? With the exception of a few people like Ginsberg, not many from the bohemian era embraced rock, and most hippies (despite the good intentions of folks like concert promoter Bill Graham) were fairly divorced from jazz.

Music hits you intellectually, physically and emotionally. In San Francisco in the ’60s, folkies encountered LSD and the Beatles and created a music that synthesized the values of all those various artists that preceded them. There is something that I can’t articulate but am confident is there that links loud volume and LSD, which causes a powerful influence.

How long did you work on the book and how did you conduct your research?

I probably researched for seven years. I interviewed Haight-Ashbury people, many of whom I’d come to know. And the San Francisco Public Library, of course.

The book is so richly detailed and you manage to tie together so many tentacles of information into a cohesive, endlessly fascinating—and yet accessible—narrative. Did you know before you embarked on this project what you were looking for, or was it more a case of having a starting point and then seeing where that would take you?

I started pretty blindly, just with the realization that the development of the hippie scene in the ’50s and early ’60s was a great story that no one had yet told. So I started reading, and eventually came up with the poets Kenneth Rexroth and Robert Duncan as the starting point.

Related: A 1976 interview with Jerry Garcia

On nearly any given page of the book, there is a plethora of names (the January 1967 Human Be-In in San Francisco alone!), and a very disparate list it is. In fact, you provide a lengthy “glossary of names” at the end. How did you determine which people were important enough to make the cut and which weren’t?

Actually, I tried to cover all the people who were mentioned more than once. The first time for any name, they need to be introduced. If they’re only mentioned once, that’s enough. But if they pop up again but it seems too much to re-introduce them, they were in the glossary. I’m sure I missed names, but then you have a computer in your hand and can look them up!

Your final chapter is on the summer of 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival. Why did you leave off there and what did Monterey signify? Were there any other events within the time period you cover that you feel were as emblematic?

Monterey was the high point, where the image of the flower child listening to great music in blissful peace was, for four days, true. There’s a great picture in my book (next to last) in which a smiling cop is threading orchids (which were handed out at the show) onto the aerial of his motorcycle. That’s a perfect symbol.

Where did it all go after hippie? And could there be an equivalent movement today (or is there already)? Why or why not?

Much of the ’70s involved developing ideas from the ’60s – things like the organic food industry and food co-ops, the personal computer, the explosion of acceptance of gay life (after hippies created the “peaceful hippie”).

I’m not sure there can be anything too close to the Haight because it developed under the radar and was really successful—through the year 1966. Then they celebrated with the Be-In and 50,000 people showed up and the media went bonkers. Nowadays, given social media and 24/7 news, it seems impossible for anything involving more than a couple of people to fly under the radar.

[The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch an interview with author McNally conducted by fellow San Francisco journalist/author Joel Selvin

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.