Record Label Exec on the Early Days and Evolution of Rock Radio

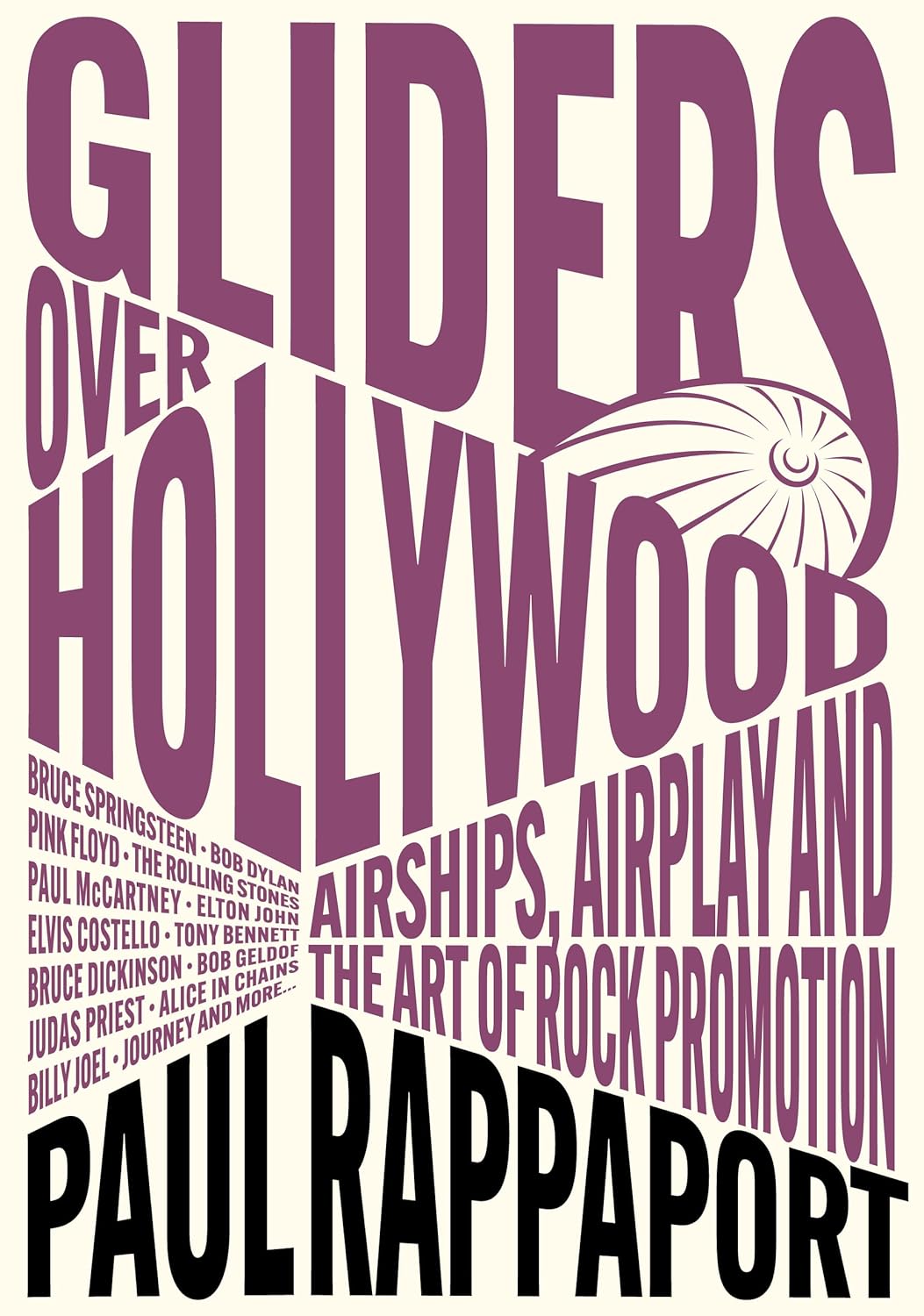

by Greg Brodsky Paul Rappaport, who enjoyed a storied career in rock radio promotion for decades at Columbia Records during the genre’s glory days of multi-platinum sales and sold-out arena tours, has published a book, Gliders Over Hollywood: Airships, Airplay and The Art of Rock Promotion. The title, which arrived on April 15, 2025, via Jawbone Press, is the executive’s first-hand account of guiding the top label’s promotional efforts to album-rock stations for releases by Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Costello, Billy Joel, Judas Priest and scores more. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Paul Rappaport, who enjoyed a storied career in rock radio promotion for decades at Columbia Records during the genre’s glory days of multi-platinum sales and sold-out arena tours, has published a book, Gliders Over Hollywood: Airships, Airplay and The Art of Rock Promotion. The title, which arrived on April 15, 2025, via Jawbone Press, is the executive’s first-hand account of guiding the top label’s promotional efforts to album-rock stations for releases by Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Costello, Billy Joel, Judas Priest and scores more. It’s available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Gliders Over Hollywood tells the exhilarating story of a blue-collar kid who grew up in thrall to rock ’n’ roll, who found himself right in the middle of many of his musical heroes’ lives as he became the most renowned rock promotion man in America.

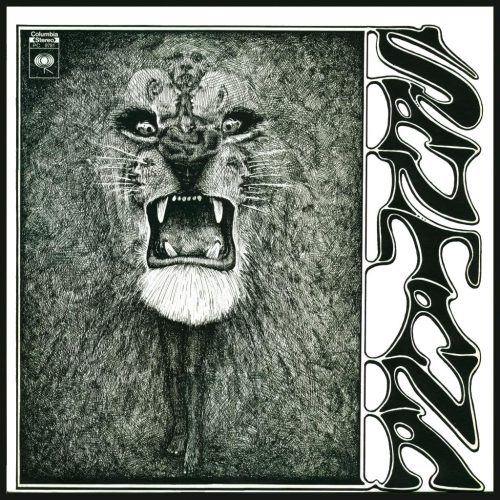

“Rap” started as a college rep while attending UCLA. “The first record I ever promoted was the first Santana album in college,” he recalls. “What did I know about promotion? Just make people aware. So that riveting black-and-white album cover, with the big lion-head graphic… I’m at UCLA, I’m gonna make book covers with that exciting album cover image. In my mind, I’m thinking, ‘This is f*cking genius! Everyone’s gonna be walking around with this lion book cover, right?’ So I make 2,000 of them and bring them to the book store and I say, ‘These are free; just give them to people.’ I wait for a week anticipating I’m going to see students all over campus walking around with these book covers. After two weeks, it dawns on me that UCLA is like a f*cking city. There’s 30,000 students! I think I saw one. (laughs) Should’ve made more.”

Not long after graduating, he became Columbia’s Los Angeles album promotion man, which at the time also included San Diego and Phoenix. There was a separate Top 40 promotion person but Rap’s initial role involved working all album radio formats. “I brought new albums from Johnny Mathis and Barbra Streisand to the adult ‘easy listening’ stations, Johnny Cash to the country stations, Miles Davis to the jazz stations. FM Rock was just starting out when I began. I loved going to the rock stations KMET, KPPC and KLOS because that’s where my heart was. A promotion person’s job is to bring music to radio programmers, give helpful information about the artist, the recording process, point out the best tracks to play, and in general make a case for that album to be added to the radio station’s official playlist. After a record is added I’d follow up with an on-air promotion—win tickets to a show, go backstage to meet the artist. Or some mega event that would make the evening news. For a new Pink Floyd album I painted the KLOS studios’ building pink, flew Pink Floyd’s giant inflatable pig overhead, shined two giant spotlights on it, and talked David Gilmour and Nick Mason into doing a live interview on the roof. It stopped traffic on La Cienega Blvd. for over an hour!

“In the book you also read about me shooting a 30-watt argon laser cannon off Signal Hill in Long Beach, California, which was a giant green laser beam that could be seen for 30 miles! It did a light show for surrounding cities as it danced to Blue Öyster Cult’s new album at the time, Agents of Fortune, while it was premiered on the rock station KNAC-FM. Kids were having laser parties on their front lawns, looking up at the sky. However, those not in the know were totally freaked out—thought aliens had landed because it looked like the death rays shot from the flying saucers from the movie War of the Worlds! Made the evening news. In my later years, the creation of the Pink Floyd airship was another huge rock marketing event.”

While the Academy Award winner for Best Director is the only one to receive an Oscar, the music business is different.

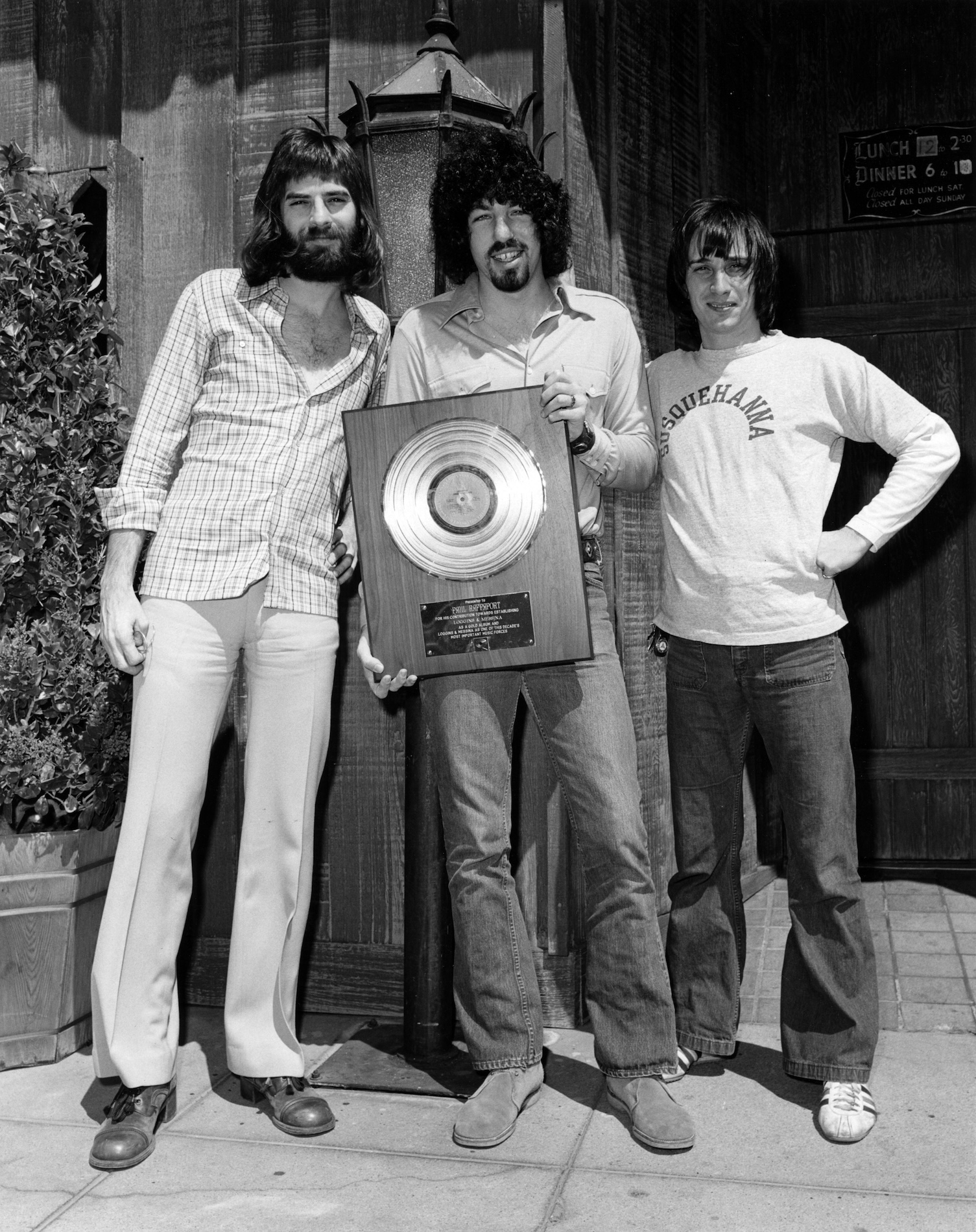

“I remember when I started and saw all the gold records hanging on the walls of the record exec offices, I wondered, ‘Wow, will I ever get a gold record? Wouldn’t that be great!’” Rappaport recalls.

“It happened during my first year at Columbia. My first gold record was given to me by the artists, Kenny Loggins and Jim Messina, for my hard work on the album Kenny Loggins with Jim Messina Sittin In. Eventually, the record company awarded them to people who played a big part in making an album go gold. But in the early ’70s everything was less corporate and more like family.

“We broke the band out of Los Angeles and then the record took off nationwide. I was invited to lunch along with my Top-40 counterpart, Terry Powell, by their managers, Todd Schiffman and Larry Larson, who we nicknamed Shifty and Larceny. (laughs) They were good guys.

“So I get there, and there’s Jimmy and Kenny and all these stacked, wrapped packages. I know what they are, gold record plaques that we’re going to give to radio as a thank you. In those days, the artists paid for them. They said, ‘Rap, you should open that one.’ I said, ‘Guys, I’ve seen gold records.’ But they insisted.

Paul Rappaport, receiving his gold album from Kenny Loggins and Jim Messina (Photo courtesy of Paul Rappaport Archives)

“I open it up and there it is: Presented to Paul Rappaport to Commemorate the Sale of 500,000 albums. It meant so much. Like I said, everything felt like a family back then, we all worked hard together to make careers happen. The camaraderie was special. FM radio was starting to become very popular and they also felt like part of the family. All of us together were trying to tell the world about this new rock music, which was exploding everywhere you looked. That’s why I did so well as a promotion man. I loved the music so much and just wanted to turn the world on to new artists like Kenny and Jimmy, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Blue Öyster Cult and Aerosmith. So this ‘family’ all wanted to get the same message out and we’re all helping each other to do that. So if you’re a radio station and played Loggins and Messina, ‘Hey, thanks. Put this gold record on the wall in your lobby. Because you helped make it happen.’”

Rock music grew so fast that lots of records went gold or platinum (one million sold). “When a project reached one of those goals, we were asked to turn in a list of everyone who helped and they would get a plaque. Over my 30-year-plus career I have been given over 70 gold and platinum records.

Paul Rappaport and his “Wall of Gold” (Photo courtesy of Paul Rappaport Archives)

“It was exciting to watch the FM Rock format and the artists grow,” he recalls. “Early on, Bruce played a theater in-the-round in Phoenix…everyone who saw that show had their minds completely blown.

“The rock radio station in Phoenix, KDKB, played the hell out of Bruce’s first two albums and he became a superstar there long before Los Angeles came around. In Phoenix, they were announcing the return of Bruce Springsteen where people were screaming and I’d tell the L.A. stations they gotta catch up or they’re gonna look stupid. In Phoenix, the mean age was 25, so the whole f*cking town is listening to KDKB. I brought the Born To Run album on a reel-to-reel tape just so the programmers and some jocks could listen to it before the album came out, because they were such fans. They said, ‘We have to play something from it.’ And I replied, ‘Oh, man, it’s not out for two weeks. I’ll get in trouble. I can’t do that.’ They were like, ‘Rap, you know what we’ve done for this guy. You gotta let us play something from this tape.’ So, I say, ‘Tell you what…we’re gonna go to your night guy. And at 8 o’clock, he’s gonna play a set of music. In the middle of the set, he’s gonna play “Jungleland.” But he’s not gonna front announce it or back announce it. It’s just gonna magically show up.’

“So the evening jock does exactly what I asked, and the request lines start melting down! People are calling up extremely amped, ‘Is that the new Bruce?!!!’ And he says, ‘I can’t say. I can’t tell ya.’ People were freaking out! In those days, what did people do for entertainment? They listened to FM radio. The whole town heard ‘Jungleland!’

“Those were fun times. It’s all new and exciting when you have a new radio format that’s freeform and every jock can play whatever they want.”

I asked Rap which on-air talents stood out for him.

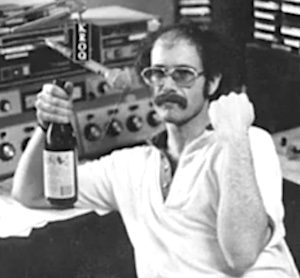

KMET’s “The Obscene Steven Clean”

“I think the two best FM disc jockeys ever were at KMET in Los Angeles. One was Steven Clean and the other was Jim Ladd. Jim’s shows were like sound paintings. He took you on a journey through music. Clean was music and talk. He was a genius, really, like Spalding Gray. He would say something that got you thinking and throughout his show he would play music that would take you down this journey that would all make sense at the end. A lot of it was social commentary. This all starts with hippies. We’re all from this hippie culture and FM radio is total granola and about people living in harmony—not about money or corporations. Even so, they have to find a way to sell advertising. Their program directors were constantly fighting the ad department…‘I’m only letting eight minutes of ads on in an hour…’ FM radio in those days was known as ‘Underground Radio,’ and it was run by a bunch of hippie freaks.

“Steven was so amazing kids would cut school so that they could hear his show at 2 p.m. They traded cassette tapes because this was an artform. I wrote about him because I didn’t want people to forget about him. I want people to know Steven Clean. Because they’re not going to believe this guy really existed.

“Those were the glory days of FM radio and eventually it got homogenized and Lee Abrams came along and made it like Top 40. But in the beginning, many shows had themes—could be songs about the weather, cowboy outlaw songs, and the jocks did segues that blended music together. The disc jockeys knew which songs had the same tempos and the same keys and which ones fit seamlessly right after another. Every jock had their own personality; each of their shows were unique.”

Rappaport’s success earned him a promotion to the label’s New York headquarters as head of national album promotion. He shares a story of a new Canadian band on the roster in 1980.

“When the first Loverboy album was delivered, I didn’t hear it right away. For some reason it just didn’t resonate with me. The product manager was Mason Muñoz, [son of Scott Muni, the legendary disc jockey and program director at New York’s WNEW-FM]. He said, ‘Rap, you’re making a mistake. This thing’s gonna be huge.’ I told him, ‘I’m a professional. I’m gonna work it hard for sure. If this thing goes, great. I don’t hear them all right away.’

“Sometimes it’s not until you see a band live and then you get it, big time. Sometimes, even record company presidents miss it. Not every record man or woman hears everything. How many labels passed on the Beatles and freaking Rush!

So, I took big ads in the trades for Loverboy to get some attention and we serviced the record to rock radio. There was a fabulous disc jockey named Gloria Johnson at KGON in Portland, Oregon. She really had an ear. She was somebody I listened to a lot. She called me up one day, two weeks after the record was out and says, ‘Rap, you’ve got a hit record!’ I said, ‘What is it?’ And she says, ‘Loverboy.’ I go, ‘Loverboy?!’ And she says, ‘Yeah, I’m playing this track “Turn Me Loose,” it’s huge, the request lines are going bonkers.’ I replied, ‘Gloria, that’s all I need to know.’ I ran down the hall and said, ‘Mason, you’ve got a hit record.’ He reminded me, ‘I told you so!’ “Hey Mase, none of us hear ‘em all in the beginning but now that we know this, we’re gonna f*ckin’ nail it!”

“Turn Me Loose,” reached #6 on the U.S. rock chart and was soon followed by such successes as “The Kid is Hot Tonight” and “Working For the Weekend.” Loverboy’s first four albums each went multi-platinum in the U.S.

Sharing those stories reminds Rappaport of the plaques that are hanging on his wall.

“I still enjoy looking at them because they’re great memories. It reminds me of working with the artists. There are ones that are more meaningful, [projects] where you make a big difference. I know there are some that really never would have gotten off the ground if I wasn’t the guy sitting in that chair at the time.

Psychedelic Furs? He mentions two veteran radio programmers. “Scott Muni at WNEW in New York and Sky Daniels at WLUP in Chicago. Two people! That’s it. Nobody else wanted to f*ckin’ play it. Nobody at rock radio heard it initially, and I had to fight tooth and nail to get that band played in the beginning.”

Midnight Oil: “‘Beds are Burning’… that’s not a rock song, right? A station that never plays anything new, WEBN in Cincinnati, gave it a shot and then we had to fight from there. Again, we were able to break the band because that song got such a great reaction on the air but it took a lot of convincing other programmers because the music wasn’t down-the-pike rock. Turns out WEBN played it just in time because when some stations didn’t help us out just a little bit every so often, we’d go, ‘Let’s just not do business with them anymore. Don’t give them any tickets to give away, etc.’

“Our rule was, even tight-listed radio stations have to walk our way at least once in a while. Or, we would ‘go out of business’ with them. My second-in-command, Jim Delbazo, used to call it ‘blowing up a radio station.’

“Delbazo used to come in my office. ‘KBPI in Denver… I just blew them up. They’re just not playing our records and I told them, “That’s okay. If you can’t play some of these newer records, why don’t you take all of the Columbia Records out of your library. Pack ‘em all up, put ‘em in a box. I’m giving you my address. Ship them all back to me and don’t play any Columbia Records. None. Guess what? You and I are out of business, We’re not calling you anymore. Don’t call us for anything.’

“And the station would say, ‘Yeah, well f*ck you.’ And then in a couple weeks they would realize that Bruce Springsteen or one of our other superstar acts were coming to town. So, if we told them, ‘Please just lose our phone number,’ that meant they were losing the phone number that connected them to Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, Billy Joel, the Rolling Stones, etc., etc. Some programmers would call back in two days. Sometimes they’d call in a week… sometimes in two weeks. But invariably they’d all call. ‘Rap?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Uh, I had this issue with Rocky [Delbazo’s nickname]…’

“And I was the guy who made it okay. I’d say, ‘Look, everyone’s radio station is different. We don’t expect everyone to play everything. You just have to take a step our way once in a while and play something new that helps us break a band.’ Some stations have tight playlists, some are looser. But if they never, ever take a step our way, how am I supposed to say, ‘Thanks for nothing and here’s a block of Bruce Springsteen tickets to give away?’ I can’t do it. Because the guy across the street is helping, and the guy in the next town is helping, and you’re making my job harder to help you. My job is to help get you as many listeners as you can because I want you to be successful because you’re playing our records.

“And we’d talk about a new band and I’d say, ‘Have your night guy spin it. If it works for you, then play it, but at least just take a step our way.’ So we’d have those kinds of battles.”

Want more? Rappaport recalls a meeting with Columbia senior exec Dick Asher about a new band, Men at Work. “He walks in and said, ‘This is blowing up in Australia. We’ve got to break the band here. Rap, you’ve got to do it.’ It’s another band with a different sound, not exactly rock. Again, I’m thinking, ‘I’m not sure about this one.’ But I’m a pro so I say, ‘Okay.’ Went out, did my job and the rest is history.

“Down Under” became a multi-format #1 smash and its album, Business as Usual, also topped charts worldwide, with U.S. sales of more than six million. Men at Work won the Grammy Award for Best New Artist.

Paul Rappaport on stage with Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and Nick Mason (Photo courtesy of Paul Rappaport Archives)

“I wrote this book to capture the magical times in the record business from the early 70’s through the 90’s. I want readers to have fun like I did. So it’s written in a ‘you are there’ style. Through my eyes the reader has conversations and unbelievable adventures with Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Billy Joel, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Elvis Costello and so many more. There’s a fencing duel with Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden down the hallways of Columbia Records, Keith Richards gives me a guitar lesson, I get to play live on stage with Pink Floyd at the London Arena. And you get the inside track on all the wild things we did to make it all happen.”

[Rappaport’s book, Gliders Over Hollywood: Airships, Airplay and The Art of Rock Promotion, is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

4 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationThe mistake that many radio hosts or DJs make is thinking that they themselves are THE artist.

The musicians are the artists.

The job of the radio DJ is to celebrate the musicians, not to celebrate themselves.

I came out of the 70’s as young hippie despising the punk movement that had begun to annihilate the classic rock I loved. In 1980 I started working in a record store chain and then moved to a local independent. That’s where the fun began. We were closely aligned with a local classic rock station. They also sold used music. The DJs would bring us the stuff that they either got too much of or had already written off. We spun that in the store. Often we would call them back and say do you realize you’ve missed such and such as an artist. You really should be playing this. Very often they would take our advice.

Also in that interaction, we were the ones that would feed them source music for their theme shows. I used to laugh in that a DJ might call me and say I need six songs about food in 40 minutes, can you do that? Working in the independent stores pre-computer, pre cell phone, our job was to be music historians and know what was on the albums and a little bit about them as customers came in looking for songs or music. So of course to come up with a few songs about food was no challenge. But that was half the fun. My reward, some 40 to 45 years after having worked this circuit are the local musicians that I’ve run into that have thanked me for the music that I turn them on to back in those days. These were Glory Days, I look back on them often.

I remember when ‘Turn Me Loose’ came out. You could play the 45 edit in the daytime, and the LP version after 7pm. The intro was a killer, and then the howling: “I was born to run . . . “.

By 1980, Columbia was a little more tolerant of long intros, as opposed to the early 70s Chicago 45 edits, which could be brutal.

It’s a good book. I think Paul absolutely nails the evasive(?) or singular nature of Bob Dylan. The best thing about ‘Gliders” is, it was written by a true fan of music. The love shows.

Everyone who comes to BCB will get that immediately. Because we all share the sentiment.

Sounds like a fascinating read right in my wheelhouse since I grew up in the 70s with the wonderful WNEW in New York City with Scott Muni, Dennis Elsas and Vince Scelsa etc.. that’s when FM radio was truly magical with the king biscuit flower hour, and they would play whole albums when they were released. I remember when I heard Bob Dylan‘s desire I believe and the who who are you.. Agents of Fortune by Blue Öyster Cult was a personal favorite.