Of Bruce Springsteen, John Hammond said: “He’s one of the greatest talents I’ve ever come across.”

If the late Columbia Records talent executive John Hammond had signed either Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen, his legacy would be golden. To have signed all three—as well as discover such talents as Billie Holiday and Stevie Ray Vaughan—puts him in his own special category.

This Q&A with the legend originally appeared in the September 30, 1972, issue of Record World, a music industry publication, when Hammond was 61. We’re proud to run a substantial two-part excerpt of it, conducted by the magazine’s editor, Michael Sigman. This is the first time it has appeared since 1974. Part one, which focuses largely on his signings of Franklin and Dylan, can be read here.

[Sigman’s introduction to the interview is reprised here…]

John Hammond is Director of Talent Acquisition for Columbia Records, the company he has been associated with almost continuously since 1932. His career, still very active, has included the discovery of many of the greatest American artists, from Billie Holiday to Bessie Smith to Bob Dylan to Aretha Franklin.

[The conversation continues with Hammond’s discussion of his run-in with Columbia Records’ A&R exec David Kapralik…]

But my real fight with Kapralik was, I had gone over to England in the summer of ’62, and I came back and found that Columbia was into something called “pop-gospel.” And pop-gospel was a musical abortion the like of which there has never been. It was taking music that did have sincerity and guts, and cheapening it for the white what Menken would call “booboisie.”

So I came back and I was horrified. Because he had taken good groups and deballed them. And so I made my feelings known in no uncertain terms. Well, unfortunately, because he’s a good friend of mine now, David had some feeling that I was in some way threatening him. So he demanded my resignation. I said, “Are you kidding? This is the business that I love; I’ve got a good job here. You can fire me, but you can’t make me resign.”

Then he made a terrible mistake; he went to the trades, and said that I had submitted my resignation. So I found out before publication, and I told the trades that I would sue them if they printed it. I won that particular thing. It’s not a good idea to have confrontations like that in a company, because I denounced Kapralik before the entire company, which was not a very nice thing to do and I realize that. But what he did to me wasn’t very nice either.

Anyway, we are good friends today, and I tell this only to show that I have offended a few people, and I continue to offend a few people, and I think maybe this is the only way that one can survive for 40 years without going crazy or becoming a yes man or becoming bland, because that’s the last thing I want to do.

What happened next?

After the fight with Kapralik I got a really bad heart attack, which almost kept me out of the business–it removed me from Columbia for six months, in any case. But good things did happen after that–I did come up with a few other people and the reissue thing was going very well. And Columbia by this time had the incredible luck of getting Clive Davis. And Clive Davis was the man who saved my life with Dylan.

How was that?

Well, Clive came back to Columbia just after I did, and it was Clive who got the letter from Dylan’s lawyer signed by Dylan, saying that he was a minor when he signed with Columbia. So Clive just asked one question: Has he been in the studio since he turned 21? And I said sure, and Clive said, “Well, in that case that validates the contract, and that letter isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.” I always had respect for Clive, but I never knew he would become as great a president as he has, because he was the antithesis of [Goddard] Lieberson, who was an aesthete, who was a composer, who was a novelist, who was a great wit and who was not superficially a businessman although he was a hell of a businessman.

But just by hard work, and really with incredible intelligence, he’s become an incredible president. Not that we always agree about everything, because of course that’s not true, but he’s a great guy to work for.

That about brings us up to the present. What are you doing now?

Well, I latched onto a young folksinger a few months ago who I just think is going to be absolutely a giant. He’s Bruce Springsteen, a good Catholic boy from New Jersey. [Springsteen auditioned for Hammond on May 2, 1972.] He’s one of the greatest talents I’ve ever come across. Whether we’re going to get it on wax or not I don’t know. That’s how old-fashioned I am—I still say wax instead of tape.

In 2022, Springsteen posted a video to celebrate his 50 years on Columbia.

Listen to Springsteen’s 1972 demo recording of “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City”

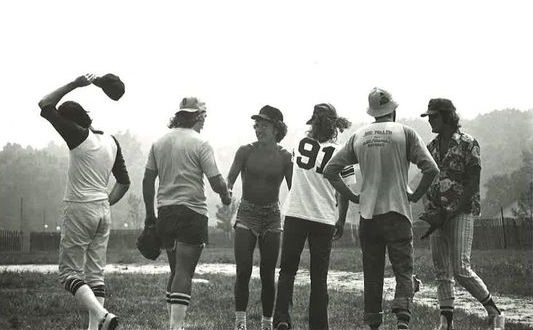

[Several years after this interview, the Record World softball team, the Flashmakers, would take on Springsteen’s team, the E Street Kings, in a 1976 tripleheader of epic proportions. That’s the shirtless Boss shaking hands afterwards.]

Record World Flashmakers vs. the E Street Kings, 1976 Red Bank, NJ. Springsteen is third from left. (Photo: Ira Mayer; used with permission)

I brought Loudon Wainwright into the company a few years ago, and I guess nobody else at the company had quite the enthusiasm that I did at the time. And maybe it’s a good idea that now he’s gotten a couple of albums out of his system because he’s going to be a giant.

There’s also the John Hammond Collection.

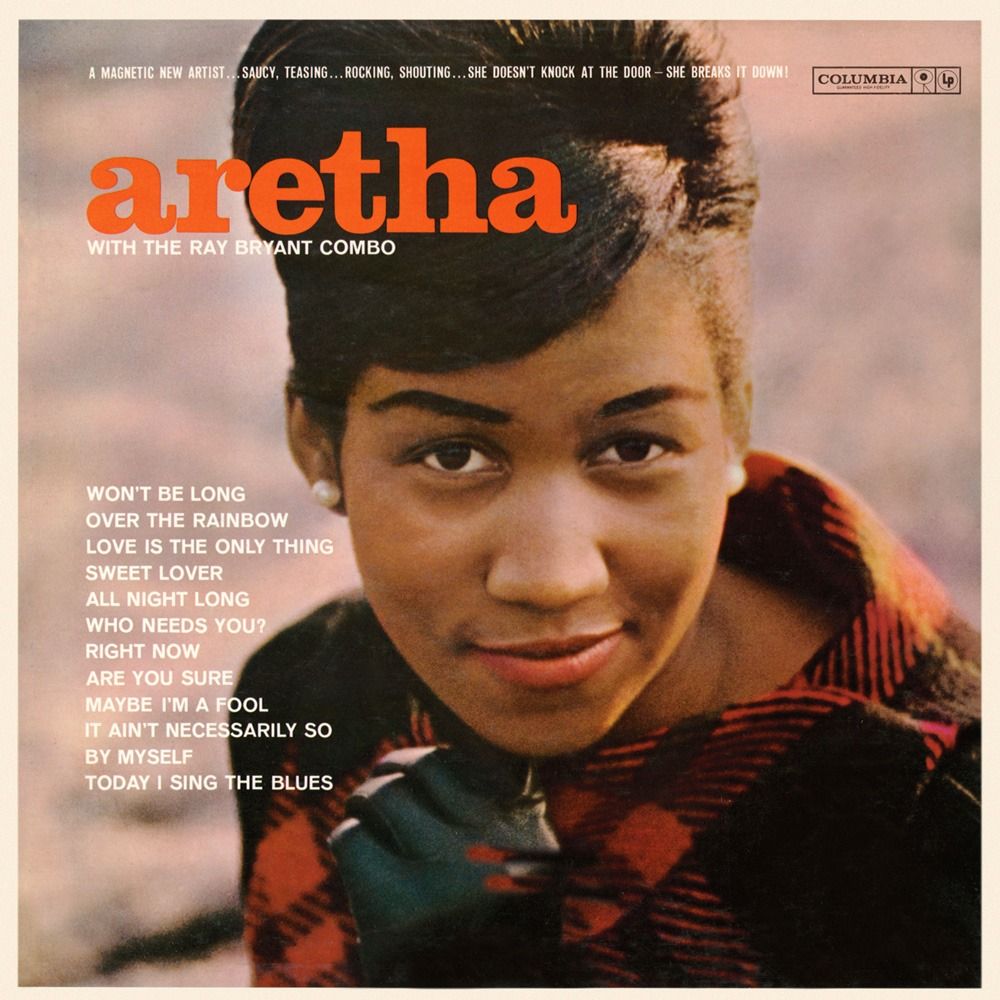

The cover of Aretha Franklin’s 1961 Columbia debut describes her as “a magnetic new artist”

There’s going to be a very nice addition. I found out that Columbia, by some incredible misjudgment, and probably a foul-up by the computer, had deleted the first album by Aretha Franklin, Aretha, which is, I think musically, the best thing she’s ever done for anybody. I found out about it in the damnedest way. Rolling Stone was doing a piece about Aretha so they finally decided that maybe they better come to me about the early days. So this nice guy from Rolling Stone asked me if I was pleased with any of the albums she did here and I said yes, the first album was the best thing she ever did. So I called for it from archives and they said it had to be returned immediately because the album was cut-out, and I said what?!

So we brought the album up here and we played it, and you know most of the people up here had never heard it and they went and then screamed. It has “It Won’t Be Long,” “Today I Sing the Blues,” “Are You Sure,” just hit after hit after hit. And so I took it right up to Clive, and I guess it was [Columbia Records exec] Bruce Lundvall who suggested we put it in the John Hammond series, and I said fine, that’s the one way it will be sure not to get cut-out again. This is the 18-year-old Aretha with marvelous musicians behind her. I wanted Aretha to be R&B but such that she wouldn’t be sneered at by the jazz audience. I never wanted her to fall into the trap that Dinah Washington did. Dinah was a hell of a singer, but she finally got so commercial that her records no longer had much substance.

Has that happened anywhere along the way to Aretha?

No. I think [Atlantic Records producer] Jerry [Wexler] rescued Aretha. He said to me recently, “You know, John, we followed what you did with her; we put her back in church.” And to me that was the biggest compliment I could possibly have gotten. And when Jerry asked me to do the liner notes on Amazing Grace I was overwhelmed. Because that’s an album I love; I know a lot of the purists don’t love it but I do. No, I just think that for my dough Aretha’s the best female vocalist to come along since Billie [Holiday].

What about the current state of music? Are we in a doldrums as so many feel?

No, not at all. Rock is not dead by a long shot, it’s just undergoing a transformation. Because we’ve got these incredibly sophisticated people in rock these days, and you’re not going to be able to keep rock down, ever.

Hammond was born on December 15, 1910 and died July 10, 1987. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.