In June 1977, the United Kingdom was anything but united. Nationalists and fans of the royal family were in the middle of celebrating their beloved Queen Elizabeth II’s 25th anniversary on the throne. For many younger Brits, the Silver Jubilee was an unwelcome background to the Summer of Punk. Across the nation, mohawk haircuts, repurposed bondage gear, torn jeans, Doc Martens and snotty attitudes proclaimed a fashion and cultural revolution was underway, parallel to the musical rebellion kick-started by a visit by the Ramones to London a year before. Hundreds of new bands seemed to spring into existence in the course of 12 months, vowing, in the words of the Clash, there would be “no Elvis, Beatles or Stones in 1977.”

In June 1977, the United Kingdom was anything but united. Nationalists and fans of the royal family were in the middle of celebrating their beloved Queen Elizabeth II’s 25th anniversary on the throne. For many younger Brits, the Silver Jubilee was an unwelcome background to the Summer of Punk. Across the nation, mohawk haircuts, repurposed bondage gear, torn jeans, Doc Martens and snotty attitudes proclaimed a fashion and cultural revolution was underway, parallel to the musical rebellion kick-started by a visit by the Ramones to London a year before. Hundreds of new bands seemed to spring into existence in the course of 12 months, vowing, in the words of the Clash, there would be “no Elvis, Beatles or Stones in 1977.”

Despite being banned by the BBC, the Sex Pistols’ snarling single “God Save the Queen” was ubiquitous, and posters, pins and shirts showed Elizabeth with a safety pin through her nose, obscured by a swastika, or covered in ransom-note lettering. British major labels and independent record companies were on a signing spree, scooping up not only hardcore punk bands but other acts that attracted the more commercial marketing term “new wave”: the Damned, the Clash, the Adverts, Buzzcocks, Boomtown Rats, Ian Dury, Elvis Costello, Graham Parker, the Jam, the Stranglers, X-Ray Spex…

Joe Jackson, a pianist and singer from the seaside town of Portsmouth, had been trained at the Royal Academy of Music, before getting experience in some pop and cabaret bands. “I was really into classical music, as it happens,” he told the New Musical Express’ Charles Shaar Murray. “I was a slightly odd teenager.” He later claimed he only went to music school to avoid working in a factory or other menial job. He felt the pull of a music career, but what kind?

Hearing Bob Marley in 1973 turned Jackson into a reggae fan, and then 1977 presented a whole new scene. Seeing the new bands, Jackson was puzzled, but enthusiastic: “At first I thought, this is ridiculous. I used to really laugh at it; I thought it was really funny. The Damned, I thought, were great; they were the first punk band that I got into because they seemed so outrageous. They were totally over the top. And then I saw the Clash, and they made me realize…they really mean it, these people. That was a definite influence.” The pub-rock blues/R&B scene led by the Southend group Dr. Feelgood was also pivotal, appealing to Jackson with their more melodic approach.

Booking a studio in Portsmouth, Jackson got together some musicians to record a fistful of songs he’d written, and those demos got him signed as a songwriter to Albion Music, which set him up with John Telfer as professional manager, quickly leading to the producer David Kershenbaum signing him to A&M Records. The whole process took about a year; sessions for the album that became Look Sharp! materialized in August 1978 at Eden Studios in London, with many tracks being first takes of a band playing live, without subsequent overdubbing. The group is super-tight, executing the interlocked parts of Jackson’s arrangements with authority. Dave Houghton is the drummer, Gary Sanford plays guitar, Graham Maby commands on bass and Jackson contributes piano and harmonica while singing every track like his life depends on it, which in a way it did.

Most debut albums don’t come with this level of expertise and power. On his website, Jackson explains Look Sharp! “positively reeks of London 1978-79…for a first album, this one’s not bad, but I was only 23 when I made it and it would be pretty weird if I didn’t think I’d done better things since.”

Considering Kershenbaum’s previous work with Joan Baez, the Ozark Mountain Daredevils, Cat Stevens and Elkie Brooks, his championing Jackson’s reggae-punk hybrid might seem strange, but there’s no doubting his ability (with Rod Hewison and Aldo Bocca engineering) to capture the fervor and spontaneity of the band, and the impressive 11 songs that made the final cut. It’s a coherent piece of art with nary a dull moment.

“One More Time” leads off Look Sharp! with brittle, jagged guitar lines, prominent bass holding it together on an equal footing with drums, and lyrics about the end of a relationship. In his memoir A Cure for Gravity, Jackson writes, “I bought a cheap secondhand upright piano and worked on it, with a driving guitar riff and anguished lyrics. The guy can’t believe the girl wants to leave: ‘Tell me one more time.’ I’d taken a little piece of my breakup, one moment, one feeling, and embellished it into something else. I guess that’s how fiction works: not creating something false, but creating new truths out of bits of old ones, just as we create new music by endlessly reshuffling the same old chords and scales.”

“Sunday Papers” is sardonic storytelling and social commentary, wrapped up in a peppy reggae beat: “I got nothing ’gainst the press/They wouldn’t print it if it wasn’t true/If you want to know ’bout the gay politician/If you want to know how to drive your car/If you want to know ’bout the new sex position/You can read it in the Sunday papers.” On an album with very little instrumental soloing, this one gets an amusing harmonica interlude.

In the U.S., “Is She Really Going Out With Him?” made it to #21 on Billboard’s pop chart when released as a single along with the LP in January 1979. In his book, Jackson describes it as “basically a funny song,” and recalls, “Everyone liked it. It was catchy, they said, and had the makings of a hit. I wouldn’t know a hit. I protested, from a hole in my head. I liked all my songs, and if I’d written a hit it was by accident.” He heard the song title on the “New Rose” single by the Damned without realizing they’d nicked it from the Shangri-Las’ “Leader of the Pack” intro. Like just about every Look Sharp! track, it’s got drama, wit, and a killer sing-along chorus. The bridge section (“If looks could kill”) is expertly placed to set up the rousing ending.

Especially in his early days, Jackson had to contend with some critics’ constant comparisons of his love songs to those of Elvis Costello and Graham Parker. He often pushed back, as he told Murray: “I want to get right away from all that macho sh*t, but at the same time I don’t want to do the Elvis Costello god-I’ve-been-hurt-in-love thing either, even though songs like that do try to put forward a realistic approach to relationships. I think my songs are all the songs of a survivor rather than…cultivated hostility.”

“Happy Loving Couples” starts with Maby’s fat bass, and according to Jackson examines relationships that might not be all that authentic, without “taking a slap at an easy target, let’s-knock-marriage.” Any melodic resemblance to Costello’s “Miracle Man” is strictly coincidental.

Side one of the original LP ends with an almost-out-of-control rocker, “Throw It Away,” driven by some Jerry Lee Lewis-style pounding piano and Sanford’s slashing guitar (perhaps influenced by Dr. Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson). There’s a whole lotta echo on the vocal.

“Baby Stick Around” is the album’s shortest track at 2:36, and sounds like a somewhat underdeveloped ’70s incarnation of Eddie Cochran. It’s even got some well-placed background and harmony vocals.

The tongue-in-cheek title track that follows is a musical potpourri. It contains 1950s pop elements, and several changes of tempo (including a Latin rhythm Jackson will revisit later in his career), all put into a mixer with jazz chords. The chorus flirts with funk, and “Look Sharp!” even has a brief drum solo.

Related: 10 songs that defined new wave music

“Fools In Love,” which Jackson describes as “the only really bitter song” on the album, is undisguised reggae, and one of the LP’s highlights. Houghton, Sanford and Maby do a creditable imitation of the Wailers, but when Jackson solos on piano it’s straight jazz, offering a nice contrast. The lyrics are pointed: “Fools in love/Are there any creatures more pathetic?…I say fools in love are zeros/I should know/I should know because this fool’s in love again.”

“(Do The) Instant Mash” refers to Jackson’s unsuccessful tenure working at a retail establishment: “In the supermarket there is music while you work/It drives you crazy, sends you screaming for the door/Work there for a year or two and you can get to like it/I don’t work in supermarkets anymore.” To emphasize this is Jackson’s version of the blues, there’s a gritty, twisting, repetitive guitar riff and a harmonica solo.

“Pretty Girls” begins with a lyrical reference to the ’60s song “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” (“Here she comes, just walking down the street”) and becomes basically a song of complaint about tantalizing females: “They say the miniskirt is coming back in style/I say it’s not fair, but what do they care.” In a 2019 interview for Entertainment Weekly about his worst songs, Jackson picked out “Pretty Girls” and said, “In retrospect, it’s kind of a stinker. It’s embarrassing—ogling girls. I mean, that’s kind of lame. It’s just childish and silly and derivative, but I was 22 when I wrote it. Not everyone can be a prodigy!”

Look Sharp! ends with “Got the Time,” at a suitably frantic pace for the words, “Wake up, got another day to get through now/Got another man to see/Got to call him on the telephone/Got to find a piece of paper.” In the middle the track becomes a Yardbirds-flavored rave-up, the dexterous Maby soloing and the whole band crashing to a conclusion on the sound of a very fast metronome.

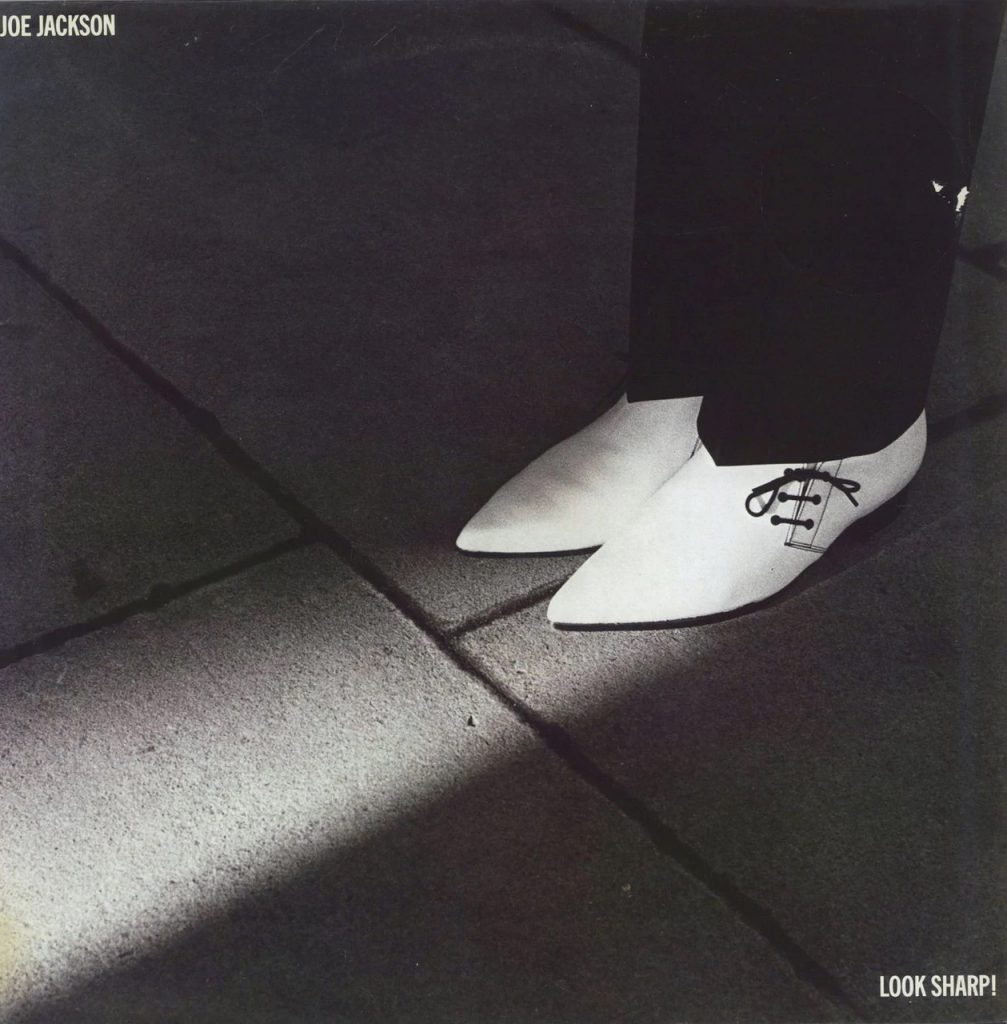

With a striking Brian Griffin-shot black-and-white cover photograph of Jackson’s “winklepicker” shoes caught in a shaft of light, the album was released only five months after it was laid down. Griffin says Jackson didn’t like the front cover because it didn’t show his face (he does appear in a suit and tie pointing at the viewer on the back cover), but the design was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Recording Package and has become iconic over the years.

After his successful follow-up album I’m The Man, recorded in March 1979 and released in October—he’s referred to it as “Look Sharp! Part Two”—Jackson’s career went from strength to strength. To date he’s recorded 20 studio albums in a variety of genres, including classical and jazz titles, and been nominated for numerous Grammys, winning for Best Pop Instrumental Album in 2001 for his ambitious Symphony No. 1.

Jackson’s latest studio album is 2023’s What a Racket. His recordings are available in the U.S. here and the U.K. here. When he tours, tickets are available here and here.

Watch Jackson perform the title track live in 1983

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationIt’s expected for Jackson to downplay his debut album, especially in light of all the stylistic changes and variety of his whole catalog. But for many of us who still love straight-up power-pop, Look Sharp! is tough to beat and is still considered his best album by many.

Absolutely one of the best albums of the 70s what a fantastic set of songs some real adrenaline fuel tunes like one more time look sharp etc Sunday papers is great. The whole album is solid and the band is just top-notch. I wasn’t much into punk, but this one did it for me I guess it would be more new wave, but still had a lot of rockers

metronome? nah… i hear a clock ticking…

also, i would like to say..”what a f$$king bass! great article, mark!