When a key member of a successful band decides to produce a solo album, it can be a tricky thing. Is there some unmet need or dissatisfaction being addressed, perhaps a hidden desire to break up the group? Are there artistic tensions and personal jealousies that need to be dealt with, and commercial considerations that add further complications? And, if several projects are proceeding at once, which musicians are involved and who claims which songs?

When a key member of a successful band decides to produce a solo album, it can be a tricky thing. Is there some unmet need or dissatisfaction being addressed, perhaps a hidden desire to break up the group? Are there artistic tensions and personal jealousies that need to be dealt with, and commercial considerations that add further complications? And, if several projects are proceeding at once, which musicians are involved and who claims which songs?

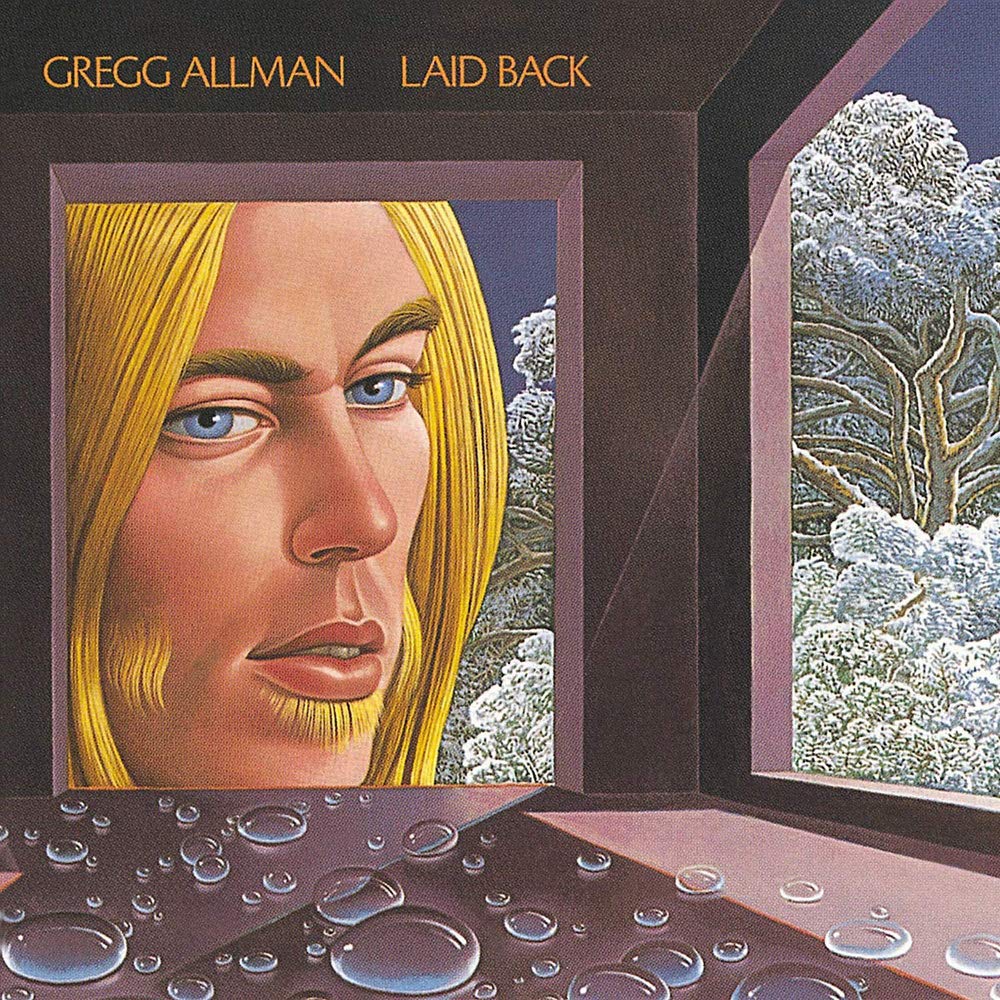

Not every solo album causes an irreparable rift, but most are to some degree toxic to the workings of a group dynamic. Such powerhouses as the Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac, the Who, Queen and the Faces have grappled with the question of what to do when a member strikes out on their own. Perhaps no band faced more internal pressures than the Allman Brothers Band during the period when they struggled to complete their first full post-Duane Allman album, Brothers and Sisters, and their main singer and songwriter Gregg Allman simultaneously worked on his solo debut, Laid Back. That the group survived and thrived was by no means assured at the time.

When the brilliant guitarist Duane Allman died in a motorcycle crash in October 1971 at the age of 24, no one was more devastated than his younger brother Gregg. With talent to burn, an intense personality and a penchant for overdoing everything, Gregg used alcohol, cocaine, heroin and hallucinogens constantly, especially once the Allman Brothers Band’s incredible live performances (and the resulting At Fillmore East double-LP) made them one of the highest-paid rock bands in America, and big money flowed. When Gregg sang his signature tune “Whipping Post” every night, he brought every ounce of internal suffering to the surface. He’d written it in the late ’60s, depressed, despairing and ready to quit his sputtering attempts at a career in music, but hard work and a few lucky breaks had transformed him from wannabe to star. After Duane’s death, as his friend Deering Howe has said, “Gregory was just not in a good place. He was in rough shape.” (Compounding the shock, the Allman Brothers Band’s bassist Berry Oakley was killed in another traffic accident the following year, not far from where Duane perished.)

Gregg Allman himself, in his 2012 autobiography My Cross to Bear, was even more blunt about his personal failings. When describing the group’s rejection of “Queen of Hearts,” a new song he’d written after Duane’s death, he wrote, “Because I was a drunk—and nobody listens to a drunk—they turned it down without even really listening to it.” The intense ballad—now acknowledged as one of the greatest of all Gregg Allman-penned songs—became the cornerstone of an album titled to immediately signal it was going to be an alternative to the hard-jamming blues-rock of the ABB.

Laid Back was always intended to go in a different direction, to be softer, more contemplative, acoustic-based, a statement of gratitude in the face of loss. Allman thought of the phrase “laid back” as that sense of ease and satisfaction he experienced when he found the right tempo and feel in the recording studio, when things clicked almost without effort. Turmoil and trauma are still detectable in the lyrics and vocals of Laid Back, but we can also hear Allman’s struggle to keep sane, healthy and upbeat. His yearning to connect is palpable; he ends the album with a version of the Carter Family’s “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” a song he’d performed at Duane’s memorial service.

In 1972, with Deering Howe helping out, Allman cut 10 demos at Criteria Studios in Miami and Advantage Street Studios in New York. It helped him sort out songs and develop arrangements (the demos are all available on the 2019 deluxe double-CD reissue of Laid Back). Among the rejects are the beautiful ballad “Never Knew How Much” (which finally emerged in 1981 when recorded by the ABB), Muddy Waters’ “Catfish Blues” and “God Rest His Soul” (a tribute to Martin Luther King written by Gregg in 1968 and never fully recorded).

Listen to the demo of “Never Knew How Much”

He also tried out three songs by his old friend Jackson Browne, two that didn’t make the cut (“Shadow Dream Song” and “Song for Adam”) and one that did, “These Days.” There are two demo versions of “These Days,” one piano-based and the other featuring pedal steel guitar.

One song, “Wasted Words,” was demoed for Laid Back but was the only example of a composition migrating to Brothers and Sisters for its final form. “It was great flip-flopping back and forth between the two sessions,” wrote Allman in his autobiography. “It was like the guy who has a girlfriend across town so as to keep his marriage together…Laid Back was my mistress.” Dickey Betts and the other band members expressed their dissatisfaction with being two-timed, but Allman didn’t care. He might be “under the influence” much of the time, but he functioned well in the right setting, and was determined to assert his artistic independence. Everyone, sometimes unhappily, adjusted.

Allman gave producer Johnny Sandlin the responsibility of gathering musicians for his album sessions, and after Sandlin finished up his work on Brothers and Sisters, the solo project took over Capricorn Studios in Macon, Georgia. Allman played Hammond B-3 organ and a little acoustic guitar. Scott Boyer, especially adept at pedal steel and slide guitar, and Tommy Talton, his guitar-slinging partner in their band Cowboy, were recruited, along with drummer Bill Stewart. The core was supplemented by several session pros, including saxophonist David “Fathead” Newman and guitarist Buzzy Feiten. Sandlin alternated on bass with David Brown and Charlie Hayward.

But the most crucial addition was the 20-year-old pianist Chuck Leavell, who Sandlin knew from the Alabama music scene. Leavell had been playing and touring with Alex Taylor and Dr. John, but was unemployed and “in limbo” at home when Sandlin called. Leavell made stellar contributions to both Laid Back and Brothers and Sisters, and subsequently joined the ABB on tour. He credits Talton and Boyer for much of the good chemistry in the studio; Talton told journalist John P. Lynskey he agrees that, “It felt so good in the room, because we all knew each other, we spent a lot of time jamming together. We were excited and energized, and the studio became our playground, our clubhouse…We all wanted to make this record special for Gregg, because we knew he was hurting.”

Related: Read a “lost” interview with Gregg Allman

Released in early November 1973, Laid Back begins with a new version of “Midnight Rider,” originally on the ABB’s Idlewild South album. Allman told Johnny he wanted this version to be “swampy,” and it does have great atmosphere. It fades in on Boyer’s acoustic guitar, then adds Talton’s echoing, eerie slide guitar and Leavell’s Fender Rhodes electric piano before Allman sings his great opening line, “I’ve got to run to keep from hiding.” As good as the ABB version is, this one tops it. Released as a single, Allman’s version hit the top 20 and helped the album move rapidly toward its gold certification for sales of 500,000 copies.

Watch a lyric video for “Midnight Rider” from Laid Back

“Queen of Hearts” is next. Feiten leads tenderly on guitar, the organ/piano interplay from Allman and Leavell is first-rate, Ed Freeman’s arrangement for horns provides dramatic support, and the self-addressed lyrics ache (“You’re gambling with your own happiness/And most all your would-be friends turn out so phony/…I’ve wasted so much time feeling guilty”). Every inch of its six minutes is interesting, and the rhythm, alternating between 6/8 and 11/8 (Allman claimed he wasn’t aware of writing in irregular time until someone pointed it out), has an irresistible swing. Pithy solos from Leavell and Newman end the track.

“Please Call Home,” another tune borrowed from Idlewild South, has a passionate gospel choir that Allman’s strong lead vocal plays off very effectively, and a tasty string section. The arrangement and singing really kicks up in volume and energy during the bridge, giving this version a very different arc than the ABB take, which features a concluding guitar cadenza this one lacks. At under three minutes, it’s a lesson on how to get to the heart of a lyric and melody and trim anything extraneous.

Listen to an early mix of “Please Call Home”

The Oliver Sain song “Don’t Mess Up a Good Thing,” originally done by Fontella Bass and Bobby McClure in 1965 for Checker Records, gets a rollicking ride from Leavell’s boogie-woogie piano, Newman’s sax, and another great Freeman horn arrangement. Allman’s singing is loose, exuberant, and fun—not a care in sight.

“These Days” features Boyer’s pedal steel, and he manages to avoid Allman’s fear that it would make the track sound “too much like a country song.” The world-weary lyrics, written by Jackson Browne when he was only 16 years old (and first recorded by Nico in 1967), benefit mightily from Allman’s interpretive powers. His vocal is deceptively simple, full of mourning and regret. Browne liked this version so much that when he finally recorded it himself later that year on For Everyman, he thanked Allman for the arrangement.

“Multi-Colored Lady” fades in on Talton’s improvised intro, and he’s joined on acoustic guitar by both Allman and Boyer. Again, Leavell’s piano is central to the track’s beauty, framed by Freeman’s best string arrangement. It’s got a gorgeously sad melody, and some of Allman’s most Dylanesque lyrics: “I sat next to a broken-hearted bride/She was crying, trying so hard to hide her selfish sorrow/I tried to get her talking/She didn’t have much to say/She asked me for a map to death row/But I didn’t know the way.”

The penultimate tune, “All My Friends,” by Scott Boyer, was previously heard on Cowboy’s 1971 album 5’ll Getcha Ten. Allman double-tracks his own harmony vocal, and Talton is also heard twice, with a tasty dual-guitar solo that Sandlin encouraged. Talton has always praised the generosity of Sandlin and Allman in letting the musicians’ ideas influence the shape of the album: “Gregg made us feel like it was our album as well.”

Related: Johnny Sandlin, like Gregg Allman, died in 2017. Read our farewell to the producer

The set ends with a hopeful version of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” When Allman died of liver cancer in May 2017, after a long and brilliant career in music and a life of ups and downs, disappointments and revivals, he was buried next to his bandmates Duane and Berry in Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia.

Bonus track: Listen to a live recording of “Melissa” by Gregg Allman from 1974

A deluxe, expanded edition of the album, available worldwide here, was released in 2019.

3 Comments so far

Jump into a conversationRead every word of Mark Leviton’s comments on the Gregg Allman album, “Laid Back” as it has been one of my personal favorite albums since I first heard it in 1973 when I was a 22 year old newly divorced kid still aching over the loss of my marriage. Gregg’s words comforted my broken heart and I was more than deeply saddened at his passing in 2017, it felt like losing a best friend. “Laid Back” has remained in my Top 3 albums of all time for nearly 50 years. Thank You Mark for reminding me of exactly why I have been a Gregg Allman fan all these years. I’m 70 now and still have it in my playlist and listen to it all the time, it just gets better with age!

Well said!

I go back and read this now and then.

Thank you

Michael Sears 01/04/2022