Andrew Gold’s ‘What’s Wrong with This Picture?’: All In the Family

by Mark Leviton

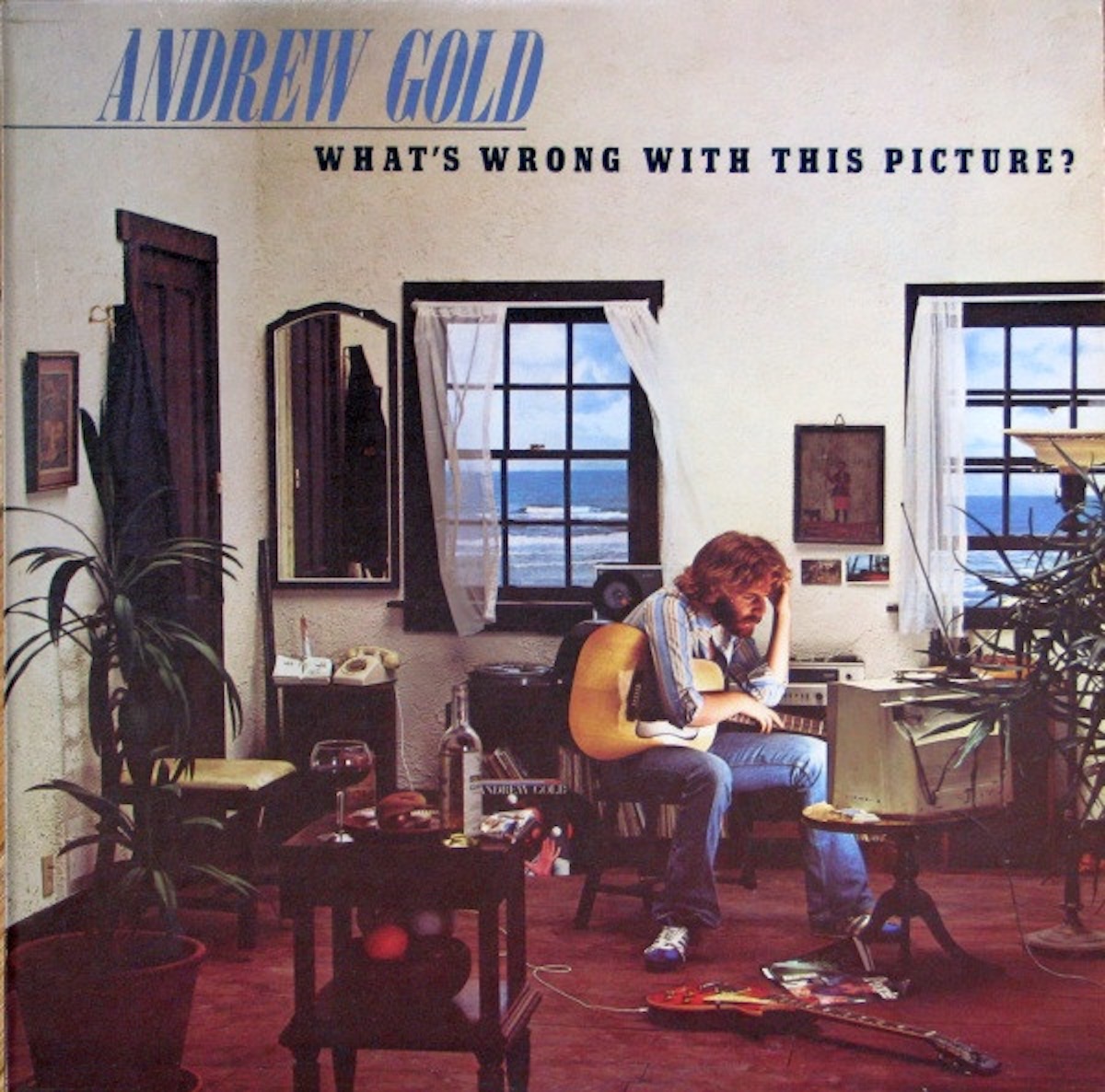

“The clever album cover, with a design by John Kosh and a photo by Ethan A. Russell, sets you up for a good time.”

Picture the scene: 1966, Los Angeles, on one of the streets winding through Laurel Canyon, where the hippest musicians—Frank Zappa, Joni Mitchell, Arthur Lee—lived next to “old money” Angelenos and Hollywood stars who, like Robert Mitchum and Natalie Wood, were too bohemian for Beverly Hills. The bright California sun is streaming into the bedroom of a red-headed 15-year-old kid named Andrew Gold.

Andrew’s mother is Marni Nixon, a talented singer who’s famous in Hollywood studios even as her name’s not well-known to the general public. When Audrey Hepburn sings in the film of My Fair Lady, Natalie Wood does “I Feel Pretty” in the West Side Story movie, or Deborah Kerr leads her Siamese charges in The King and I to “whistle a happy tune,” it’s Marni Nixon’s dubbed voice audiences hear.

Andrew’s dad, the composer Ernest Gold, is more openly famous. Fleeing Austria with his family when the Nazis moved in, Gold wrote symphonies as part of his continuing music studies in New York City, moving to Hollywood in 1945 to work scoring films at Columbia Studios. The Academy Award-winning Exodus score joined his work on Inherit the Wind, On the Beach and Judgment at Nuremberg in his growing list of distinguished credits.

Looking back in 1977 during an interview with Sounds’ Barbara Charone, Andrew Gold explained, “One of my fondest memories as a kid was when we were living in Laurel Canyon and I was 14 or 15. My room was towards the back of the house, and my father had this little studio with a nice huge picture window and a piano and all his awards.

“When he was working on a movie he’d go up there and compose. I’d wake up around 9 o’clock to this piano music over and over. I used to just love that, people actually working on music. All that tinkling away was neat.

“Music was never forced on me. It didn’t have to be. I wanted to take piano lessons and my parents made me practice, which I didn’t like to do and eventually quit. I couldn’t stand to practice and was too impatient to learn how to read music. I was always going to be a musician, and my parents encouraged me. I’d play them some song I wrote or some Beatle tune. And my father would say, ‘Ah, that sounds fairly interesting, rock music is getting fairly sophisticated.'”

The gregarious Gold met singer Linda Ronstadt, performing with her band the Stone Poneys, when he was still in high school, and played in his share of garage bands. By 1967, Gold had formed a band with Ronstadt’s colleagues Kenny Edwards, Wendy Waldman and Karla Bonoff, dubbing it Bryndle as a nod to the Byrds. They recorded an album, but it wasn’t released at the time.

For several years, Gold continued to work with local musicians who gathered in the Laurel and Topanga Canyon scenes, and at the Troubadour nightclub Monday “hoots,” improving his playing chops on a number of instruments, and figuring out how to write songs that were more than Beatles pastiches. In a 2000 interview with Joe Matera, he said, “I started writing songs at 13. My first was called ‘Where Is the Love,’ not to be confused with the ’70s hit by the same name. It was a dark minor song waltz…I have always had a knack for playing many instruments…and arranging ideas come easy.”

His contributions to Ronstadt’s breakout album Heart Like a Wheel in 1974, including the celebrated guitar solo on her massive hit “You’re No Good,” became his major calling card. He played on her next four albums, and toured as part of her band. Signed to her label Asylum, he released his eponymous debut LP in 1975. He wrote all 10 songs and created most of the instrumental tracks, including bass, drum, keyboard, percussion and guitar parts.

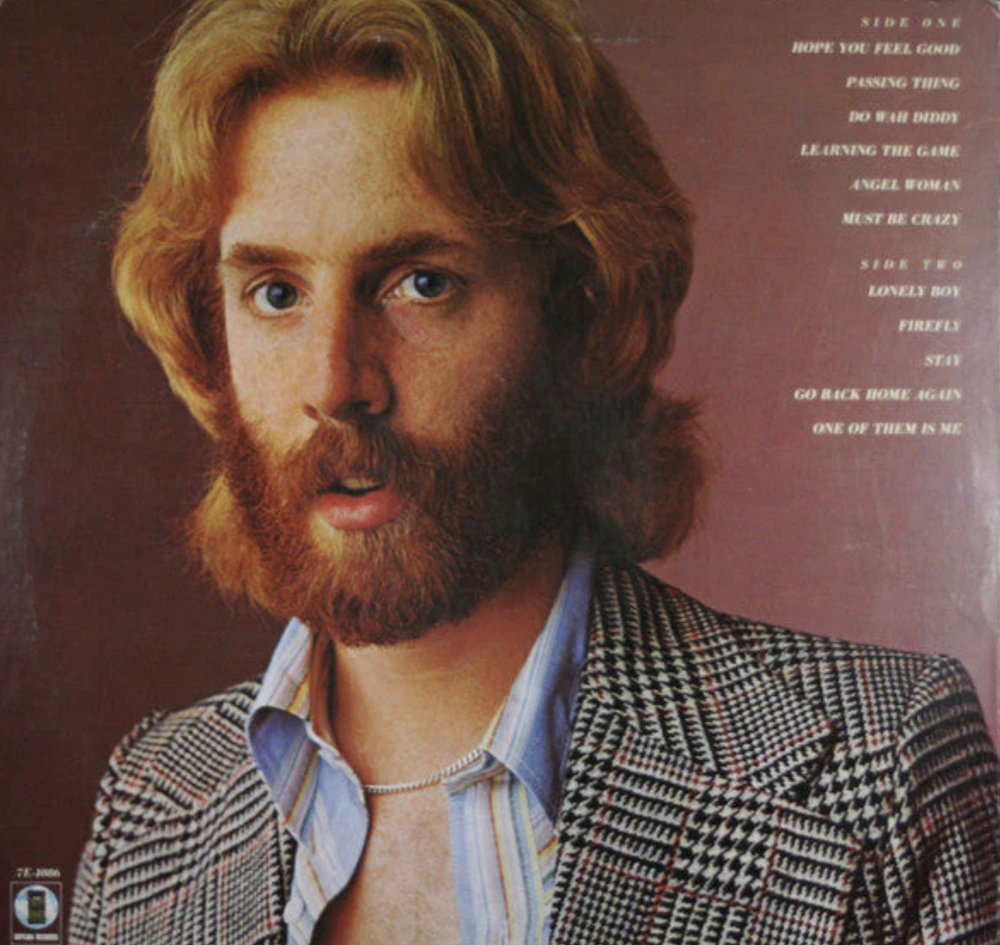

Gold’s light but precise singing fit in well with the laid-back L.A. singer-songwriter milieu, but it took him another year to find his first real pop hit, “Lonely Boy,” which reached #7 on Billboard’s Hot 100 after being drawn from his second album What’s Wrong with This Picture? This time he mixed eight originals with three of his favorite “oldies” from his childhood.

Working with Ronstadt’s producer/manager Peter Asher and engineer Val Garay, for his sophomore effort Gold concentrated on piano and percussion, using the cream of L.A. session musicians for the heavy lifting: bassists Kenny Edwards and Leland Sklar, guitarists Waddy Wachtel and Danny Kortchmar, drummers Mike Botts and Russ Kunkel, and multi-instrumentalist Dan Dugmore all appear.

“Hope You Feel Good,” which Gold co-wrote with Steve Ferguson (the only songwriting help he got on the album), is the opening cut, and it fades in slowly before revealing a strong tune that could be at home in Elton John’s catalog, sprinkled with McCartney dust. According to Gold, it’s almost entirely a first take, except for a slightly out-of-tempo “punch-in” near the end.

Depending on an infectious, bouncing rhythm, the whole thing’s delightful. The lyrics combine typical moon/June love tropes with some clever indications that the writers know they are amusingly toying with cliches: “Spring is in the air/Blossoms everywhere/The sun is shining brightly/Makes you feel good inside/When you know that love is so bona fide/On a summer night when the stars are bright/We’ll make a date and then we’ll go strolling soon/And take a look at this romantic moon/You hear so much about.”

“Passing Thing,” which Gold referred to as “a little Japanese-y watercolor of a song,” creates a pastoral picture with a bittersweet, minor-key lilt: “Slowly sailin’ leaves/The children of the trees/evicted by the wind/And can’t return again” are the opening lines. The Japanese shakuhachi flute, played by Don Menza, is an inspired bit of tint alongside Gold’s acoustic piano. The lead vocal has just the right amount of yearning, giving quiet dignity to the concluding phrases: “It’s only a passing thing/It’s only what time will bring/Though we are together thrown/We’re all alone/We can’t go home.”

“Do Wah Diddy,” the Exciters’ minor R&B hit (written by Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry) from 1964, which most people know from Manfred Mann’s hyped-up British Invasion version, is given a head-to-toe makeover. The amusing arrangement brims with ideas, from the tempo and key changes to the wealth of interacting guitars and chorus vocals, and a quick nod or two to the Beatles’ Abbey Road. The string arrangement is by David Campbell.

Buddy Holly recorded a demo of “Learning the Game” in his Greenwich Village apartment just a week before he died in a plane crash on Feb. 3, 1959. The song, with overdubs added, was released posthumously on The Buddy Holly Story LP the following year. Gold’s poignant version begins with his piano and Edwards’ mandolin in conversation, before the high, sweet lead vocal enters. Dugmore’s pedal steel, Wachtel’s bass and the well-designed harmonies handled by Brock Walsh and Gold are standouts. Perhaps Gold found inspiration for his melancholy take from Sandy Denny’s version, recorded for the Rock On compilation in 1972.

Piano and strings back up Gold on the short and lovely interlude “Angel Woman,” with the rather tepid Motown-inspired “Must Be Crazy” next. It never catches fire, and sounds like a rush job—even Kortchmar’s solo is sub-standard.

Side two of the original vinyl starts with “Lonely Boy,” a spectacular performance with an intricate arrangement worthy of Phil Spector and Jack Nitzsche, rhythmically and melodically surprising. As Gold told Matera, “It’s kind of a semi rip-off of a section of a Ry Cooder song, ‘How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live’…but barely. I just wrote the song one night in Hollywood in my little apartment, and thought it should be an eight-minute opus, but got bored after three and a half.”

The lyrics to “Lonely Boy” combine real autobiographical details (“He was born on a summer day 1951”) and a made-up sibling rivalry (“In the summer of ’53 his mother brought him a sister/And she told him, ‘We must attend too her needs/She’s so much younger than you’”), but it’s the thrilling, propulsive gestalt and catchy chorus that grabs the listener. Little touches—Gold’s cowbell, Botts’ sleigh bells, Wachtel’s stuttering lines, the harmonies of Linda Ronstadt—really elevate the track. Wachtel’s full-blown solo at 2:00 is terrific, capped with a string section briefly swooping before Edwards’ insistent bass leads us back into a reprise of the opening Beethoven-ish piano theme.

“Firefly” begins with acoustic guitar, and develops as a folky, Beatles-infused mid-tempo ballad, with Gold playing all the basic instruments. Cellos nod to “I Am the Walrus,” and Gold’s electric guitar tone is George Harrison-adjacent. Still, despite a good lead vocal, it’s pretty blah, especially after the excitement of “Lonely Boy.”

It’s followed with another misstep. Maurice Williams’ “Stay,” which he recorded with his doo-wop group the Zodiacs in 1960, is reimagined by Gold and company as a percussion-full groover that still depends on a backing chorus (with Ronstadt and Asher on board) for oomph. A hoedown briefly breaks out at the two-minute mark, contributing to a truly messy, undercooked arrangement. Gold’s attempts at falsetto are ill-advised.

Jackson Browne, with bandmates Kunkel, Sklar and Kortchmar (plus David Lindley, Rosemary Butler and Craig Doerge) began performing “Stay” in concert in 1977, including a terrific live version on the Running on Empty album in December ’77. Given the personalities involved, the odds are good the Gold version somehow migrated and improved.

“Go Back Home Again” was the first song recorded for What’s Wrong with This Picture?, while the same basic band, including Gold in a crucial role, was also working on Ronstadt’s Hasten Down the Wind album. Dugmore, Botts and Edwards are heard in support for Gold, who plays most of the other parts, the main guitar solo and lots of percussion. It’s an upbeat tune that again shows his debt to the British Invasion, filtered through some California sunshine pop.

“One of Them Is Me” concludes the disc. In the liner notes to his Best Of CD, Gold admitted, “This was one of those ‘secret code’ songs that one wrote when one, say, wanted to be more than just friends with someone else’s girlfriend. Never happened though, yet somehow this approach worked for Eric Clapton with ‘Layla.’”

Featuring Gold’s first use of electric piano on the LP, it shows off his strongest songwriting and arranging abilities, building drama through apt tempo shifts. This time his falsetto is fine, and Dugmore on pedal steel and Wachtel on electric guitar do more solid work. It’s a love song with a twist: “There’s a girl I know/So far away from here/She’s got a lover/She’s got a friend/And she’s got someone who’s always near/One of them is me/And I don’t know who.”

Despite the success of “Lonely Boy,” the album, released in December 1976, never got higher than #95 on Billboard’s LP chart. The clever album cover, with a design by John Kosh and a photo by Ethan A. Russell, sets you up for a good time, as do the extensive tongue-in-cheek inner sleeve notes Gold supplied: “One great thing about this album is Peter Asher’s production. He’s got red hair like me, so there was no linguistics problem or anything. His is darker red, sort of like mine only darker red. Val the engineer doesn’t have red hair but we got an interpreter.”

Gold continued to record in various settings, including a stint in a band called Wax with Graham Gouldman from 10cc, and recorded/produced/toured with James Taylor, Cher, Stephen Bishop and the Eagles. His song “Thank You for Being a Friend” as sung by Cindy Fee, became the theme for the TV show The Golden Girls, and he performed “Final Frontier,” the theme for another sitcom, Mad About You, even though he didn’t write it. He also loved doing low-key gigs around L.A., playing the Byrds, Beatles and Beach Boys songs he loved.

Andrew Gold was diagnosed with kidney cancer and was recovering well when he died in his sleep from heart failure on June 3, 2011, at the age of 59. He’s remembered with great affection by his many collaborators, who also appreciate the wry humor he brought to whatever he did, like the doubletalk in those What’s Wrong with This Picture? liner notes: “The great thing about music is how it always never ceases to constantly not fail to always never cease. Of course, I had to go to music school to learn that, you can’t just pick it up. You’d get a hernia.”

Lonely Boy — The Asylum Years Anthology, on 6-CDs/1-DVD is a repackaged repress of Gold’s solo years with the label between 1975-1980. It’s available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Watch Andrew Gold perform “Lonely Boy” with America in 2006

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationAndrew was a great talent who helped make other people shine. He was gone far too soon.