Phil Collins at Face Value: The Lost Tapes—Previously Unpublished Vintage Interview

by Ben Brooks

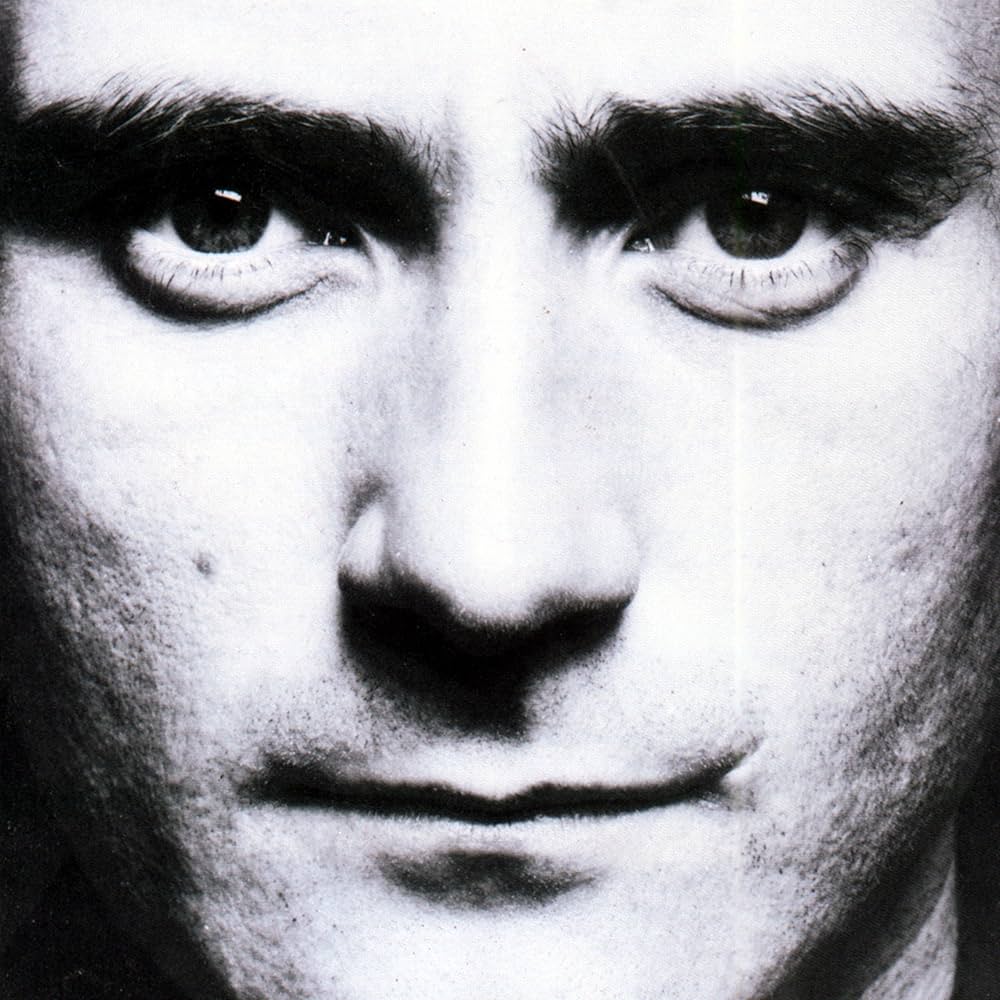

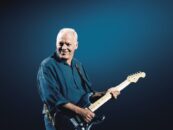

Phil Collins, in the photo used for the Face Value album cover.

In February 1981, Phil Collins stood at a pivotal moment in his life and career. After nearly a decade as drummer—and increasingly, lead vocalist—for Genesis, Collins found himself navigating profound personal and professional change. His marriage to Andrea Bertorelli had ended, and he was preparing to release Face Value, his first solo album, a deeply intimate work that marked a decisive shift from the sound and identity that had defined him with Genesis.

By this point, Collins had already been a ubiquitous presence in the late-’70s music scene. Alongside his work with Genesis, he had made notable appearances on recordings by Brand X, Brian Eno, John Cale, Robert Plant and others, quietly establishing himself as one of the era’s most versatile and in-demand musicians. Yet stepping out under his own name represented a different kind of risk—one that might not sit comfortably with Genesis’ fanbase.

At the same time, Genesis itself was far from dormant. The band was gearing up to release its eleventh studio album, Abacab, later that year, signaling another evolution in its sound and reaffirming Collins’ central role within the group. Balancing the demands of a major band with the vulnerability of a solo debut, Collins faced an uncertain but promising future.

The following interview captures Collins at this fragile yet auspicious juncture. Candid and reflective, he speaks about his drive toward independence, his continuing commitment to Genesis, and his thoughts on the musicians who shaped—and challenged—him during his career thus far.

[Ed. note: Face Value established Collins, born January 30, 1951, as a solo superstar with 5x Platinum sales in both the U.S. and U.K., and multi-Platinum success in several other countries. At the time of this interview, the single, “In the Air Tonight,” was essentially unknown in the U.S. Thanks to its extraordinary closing drum beat, it’s since become one of rock’s most recognizable songs in pop culture and has been featured in numerous movies, commercials, and sports broadcasts.]

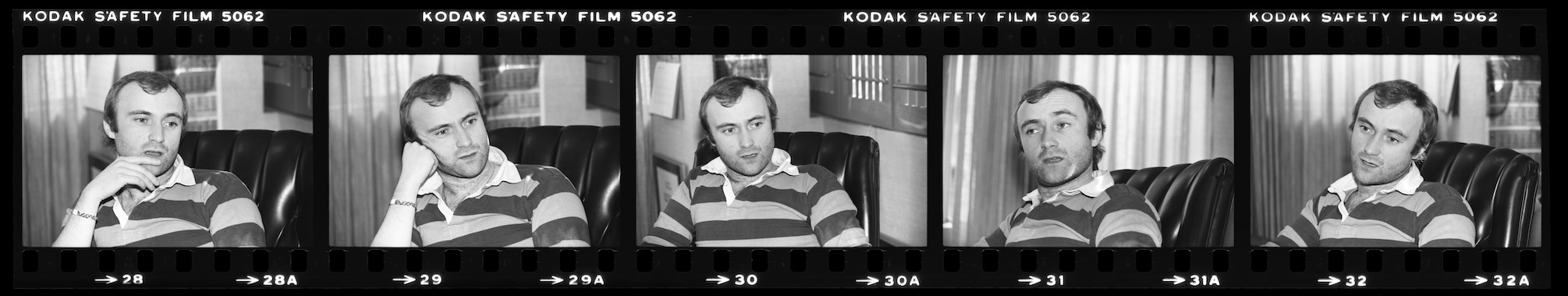

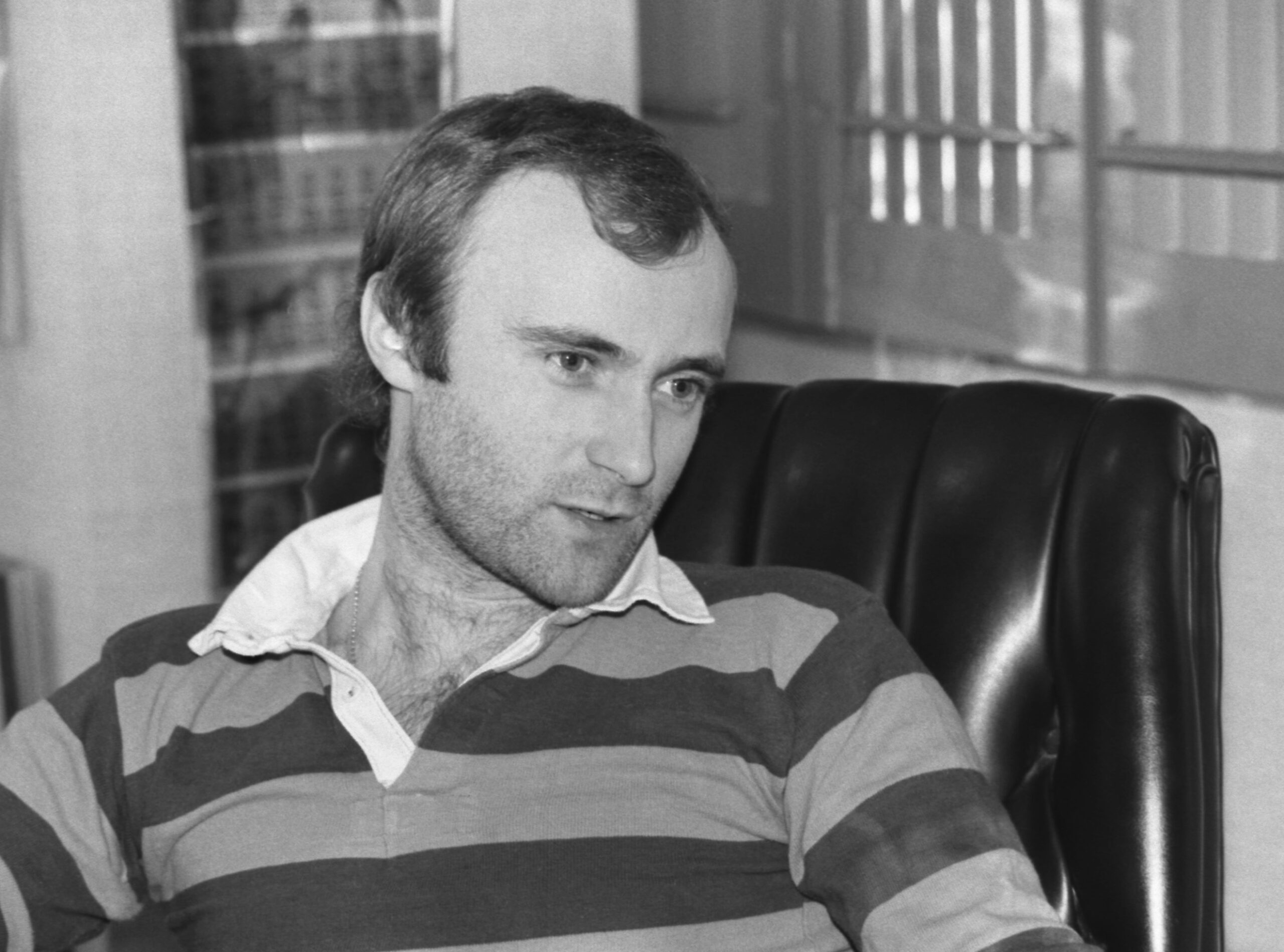

Phil Collins at Atlantic Records’ Hollywood offices, Feb. 13, 1981 (Photo © Jennifer Maxon; used with permission)

Interviewer Ben Brooks: I just heard one side of Face Value before this interview. Lyrically, it sounds like you’ve been through a tough break-up.

Phil Collins: This stuff is born out of a divorce. I was separated a couple years ago. So, you’ve got two kids and a wife who are suddenly not there. You’ve got a lot of time. In the past, I was too involved with Brand X or somebody… John Martyn, Eno, whatever, to finish my own songs. But, I had all this time alone. The album is very personal.

Was it hard to write?

It was easy. I’d written the songs at home and I just knew what I wanted them to sound like. I didn’t want anybody else’s ideas. That’s why I didn’t get a producer.

Producers can be a good sounding board, someone with objectivity who can help guide you through the creative process.

I suppose, but with a producer you’ve got someone coming in like Da Vinci sitting there saying, “Can you go and put a bit of blue up there? A bit of red? I don’t like the smile.” You’ve got to do it yourself, unless you want an interpretation. And I didn’t want an interpretation. I knew exactly what I wanted it to sound like.

Phil Collins at Atlantic Records’ Hollywood offices, Feb. 13, 1981 (Photo © Jennifer Maxon; used with permission)

How did recording in your home studio work out?

Well, I did the keyboards and the drum machine at home. Then I transferred the eight tracks onto 24 tracks at the Town House in London and the Village Recorder in L.A. I did the drums in the studio with an engineer [Nick Launay], but I produced it myself, basically.

You got some pretty impressive musicians to play with you.

I recruited Alphonso Johnson, an old mate of mine, Daryl Stuermer, L. Shankar, John Giblin and a few others…not to mention the EWF (Earth, Wind & Fire) horns.

I understand the Face Value album is coming out today [Feb. 13, 1981]. A different lead single came out in America than England, right?

The first American single is “I Missed Again,” which is the first cut on the B-side of the album. That’s probably why you got played that side (of the album). But in England, the first track, “In the Air Tonight”, on side one, is the single. And that’s #1 there right now. [Ed. note: It actually peaked at #2.]

Does the success of the single in England surprise you at all?

Very much so. We were shooting in the dark there because “In the Air Tonight” is a very demanding song. It’s a drum machine thing that cruises menacingly for about four minutes, on the album version, and then the drums come in and all hell lets loose. But when I was mastering in New York, Ahmet Ertegun [chairman of Atlantic Records], who’s been a big help with this album, suggested putting some more drums on the (shortened) single. Ahmet said, “That’s too subtle for a single. But, if you put the drums on earlier with an edit, then it could be a hit.” So I did it and it’s a hit!

The album is definitely a departure from Genesis. The songs are short, less complicated, and lyrically more pop. It’s more rhythmic, a little bit R&B.

In general terms, the album is a Black R&B album. I had a long meeting with Henry Allen, who is head of black music at Atlantic. I said, “Listen, I’m convinced that ‘Behind the Lines’ and ‘If Leaving Me is Easy’ and a couple of other cuts could be played on Black radio as long as they don’t know who I am.” So we’ve cut these little 45 singles. We’re just sending them out to a few selected Black radio stations as Phil Collins plus the Earth, Wind & Fire Horns. If they pick up on it, then maybe more will start playing it.

You’ve changed labels for this album. Did Ertegun’s enthusiasm convince you to sign to Atlantic? What was the motivation there?

Besides Ahmet Ertegun, I changed record labels because too many people have preconceptions of Genesis. Some of our fans from over the years didn’t even listen to [Genesis’ 1980 album] Duke, as successful as it was. I changed labels because I didn’t want to get put in that same box.

That would be tough especially since your album sounds more mass appeal.

Right. Face Value can definitely appeal to a lot more people than Genesis does. Some of the more radical music papers and disc jockeys didn’t like Genesis in the beginning because we used synthesizers. They always put us in the same bunch of groups as Pink Floyd and Yes. We were no more like Yes and Pink Floyd than [we were like] Elvis Costello.

Well, Genesis is certainly considered a progressive group, along with those.

It’s very hard for me to agree with any of this kind of thinking because I hate those bands. I don’t want to be slanderous, but the kind of music I listen to at home has got a bit of soul to it, a bit of heart, whether it’s Earth, Wind & Fire or jazz.

Related: In 2018, Collins opened his first tour in 12 years

Brand X sounds a bit jazzy. You’ve adapted your drumming to their music. I figured you’re into jazz.

I can’t profess to be a jazz buff, because I’ve only had sort of a flirtation with jazz through Tony Williams and Brand X. People say, “Well, you must like so and so.” And I say, “Well, I’ve not really heard them.” I do like bands like Weather Report and the original Mahavishnu Orchestra. In my mind Mahavishnu Orchestra was the best fusion band ever.

Watch Brand X with Phil Collins on England’s Old Grey Whistle Test

Weather Report has a little R&B feel. They’re really a unique band.

I don’t profess to be a Black white boy or a white Black boy or whatever, but Weather Report is Black music to me. I like lots of different types of music. When I DJ shows in England—two hours of your own music—I take along Eno, Weather Report, Steve Bishop, John Martyn, Earth, Wind & Fire and [Michael] Jackson albums. And they seem surprised, “Well, you like that stuff?”

Phil Collins in the music video for the album’s “I Missed Again.”

Are you concerned you will turn a lot of your Genesis fans off with this new solo album?

Well, to me, if they don’t like Face Value, then they don’t really like the things that I try to put into Genesis. With all my drumming, I’m trying to inject a black feel, and as much soul and groove as I can. Songs like “Turn It On Again,” “Behind the Lines” and “Duchess” from Duke are examples. I tried to put a Black feel into “Duke’s Travels.” I thought that “Turn It On Again” was as Black as Genesis had been to that point. Of course, the brass on Face Value is Blacker sounding than any Genesis album.

Watch Genesis perform “Duke’s Travels”

Now that you, Mike [Rutherford] and Tony [Banks] have done your solo records, do you think there’ll be stronger egos and opinions when you write and play as Genesis going forward? You guys have worked together for quite a while now.

I don’t think there’s that problem, really. It is possible to get a problem when someone’s solo album is more successful than the others. There’s a bit of jealousy. But not in Genesis. I mean, really, we all know each other too well and we’re pleased for each other. So I say, in terms of defining what the group does, the solo projects have helped. I do feel that the sound on my album is great and my songwriting has obviously developed. I never really finished writing a song, including “Misunderstanding,” up until this period.

You’re in a band where you’ve got all these strong personalities and everybody’s got different feelings and musical tastes from each other.

Yeah, well, that’s why Genesis is what it is. I don’t say “special” because, I mean, some people don’t think it’s special. But it is a catalyst for everybody in the band’s musical taste. So I go in there with a jazz vibe, and Tony will play some chords that are very Tony chords, English chord progressions, and you get something like “Los Endos.”

Are there plans for the next Genesis album?

For the next Genesis album [Abacab] we bought Fisher Lane Farm in Surrey and built our own studio there. We’ve written a number of tracks for it already. I know what ones I want to use. It’s just a question really of convincing the others 100 percent.

Will it continue in the direction of Duke?

It’s more group stuff, which means it would be more like the best stuff on Duke. Tony’s writing has changed a little bit because he’s been listening to a lot of newer bands. He’s learning the simplicity of things. And, Mike, too.

How are you three writing?

Now, we write together. Because what happened with Duke was that Tony and Mike had finished their solo albums and they didn’t have that much material. I had my material, but I wanted to keep most of it for my album because I wanted to play keyboards on it. So I said, “Listen, any songs that I’ve written that you like, I’m open to doing.” For Duke they liked “Misunderstanding” and “Please Don’t Ask,” which are part of my bunch. And so we did them. I wanted to play piano, but there are territorial rights, so Tony plays keyboards with Genesis! We kind of wanted to do more group stuff anyway. Prior, the group was becoming a vehicle for individual songs, which I didn’t really like. I understand that everybody wants to get themselves out there, get their songs on an album. But quite often you don’t really see eye-to-eye on something. Which is good. If you don’t want to compromise, don’t be in a band. I’m into being in a band, but I don’t particularly like the idea of playing someone’s song I don’t like.

If Face Value is a success, will you keep playing with Genesis?

Would I split from Genesis? For me doing solo albums has made the band much more clearly defined and stronger. “Turn it on Again,” for instance, was one of Mike’s rock riffs. Initially, it started off as [sings slowly], “ding-ding, ding-dah, ah ah.” And I said “No, faster, like “September” (sings “September” by Earth, Wind & Fire ). Tony will play something, and I will think of something the way I see it, and we compromise. On Duke, I didn’t particularly like “Cul-de-sac.” So, that side of Genesis will now go away, because Tony can do it on his own. Now we write together for the three of us, something that we can’t do individually. And the new album is all group stuff written from scratch in the living room of this farmhouse, where the roadies live at the moment.

When you go back and listen to early Genesis, what do you think? Or don’t you listen to early Genesis?

I don’t often. There are certain things on [1974’s The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway], for instance, “Silent Sorrow In Empty Boats.” I like the more moody music. We probably will end up doing more on this new album. It gives you that space.

What’s your favorite classic Genesis stuff?

Seconds Out is probably one of the best albums. I didn’t like some songs on …And Then There Were Three. I like bits of Trespass. I like bits of all the albums. But I’m too close to it. I just look at it as a margin of error as opposed to looking at what’s right with them.

Genesis has always had a producer, right?

No, we’ve always had a very good engineer that we called a co-producer because he was the one that, for instance, would tell us the third of five versions of a song was the best one. You want someone devoid of all involvement who you trust. And so, to be kind, we called him a co producer. Now, we’re not going to use a “producer.” We’re going to do it ourselves and use Hugh Padgham, who’s a very good engineer. He did my and Peter’s [Peter Gabriel] album. That’s all we need.

So you’re the “producer” of your album [Face Value]?

For my album, I wanted to totally direct these musicians. I told [bassist] Alphonso [Johnson] where and what kind of thing I wanted him to play. Same as [violinist] L. Shankar. I gave them direction. I got people that I thought would do what they do naturally and still fit in with what I wanted. With the bass parts, for instance, I had John Giblin and Alphonso Johnson play individually, then chose the track that worked the best.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Genesis’ Seconds Out

Eric Clapton played on a track on Face Value, right?

Clapton played on “If Leaving Me Is Easy.” He’s a neighbor of mine. We live within eight or nine miles of each other, and we’re drinking partners, really, as opposed to musical cohorts. But, he came down to the house when Face Value was still in the eight-track stage. I wanted him to play slide guitar on one song. And he played great. But, because we had a few drinks, the technical side of it was not usable. Anyway, after that song, we sort of mucked about and he played some blues for a couple of hours, and then we did “If Leaving Me is Easy.” It was just a very loose thing.

Beyond the music, were you involved with the visual concept and packaging, etc., of Face Value?

The actual label copy on my album is handwritten. The design and advertising…I have control over it all. I think, in theory, when someone buys an album, they should be able to think, this is the artist’ s vision . I stand or fall by my record. People should be able to suss out where I’m at from the whole package. I don’t want something in Billboard or an advert to say something that I’m embarrassed by. So, I will make sure that I believe whatever’s written. I feel very strongly about certain things. Too many artists record the music and then, after that, become a tool of someone’s ideas for marketing and advertising.

How do you feel about producing other people’s albums?

When L. Shankar rang me up and asked me to produce his album, I said, “Well, I’ve never done this before and I don’t really want to do it for the first time for somebody else. It’s not fair.” Simon Townshend, Pete’s brother, wanted me to produce his album. I said, “I’ve never done it before,” because at that time I hadn’t. I worked closely with John Martyn on his album Grace and Danger, which was technically produced by Marin Levan. John and I get on very well. But to be honest, with John I think all you have to do is just say, “That’s the best take.” Give him an environment that he can work in because he can be erratic. He’ll be terrible one day and great the next.

You have been recording with other artists along the lines of Clapton.

I was supposed to do bits of Pete Townshend’s last album and he’s asked me to do his next album. So that’s a priority for me because I want to work with that bloke. I like working with other people. It’s flattering when Townshend rings you up and says, “Can you play drums on my record? I’d like to work with you.” And I can’t say, “No, man, I want to go down to the pub and get drunk.” I’d rather do the work. That’s why I had Brand X, and all these other things. It has kept me fresh for Genesis.

Who are some of your influences?

I like some drummers. I believe in doing what’s complementary to the music. On “Squonk,” for instance, I put on a John Bonham hat. I asked Townshend about joining The Who because I actually can put on the Keith Moon hat.

You wanted to play with The Who?

Yeah, I’d like to have played with The Who. I just rang up and said, “Listen, you know, if I can be of any service to you, give me a call.” And I got a call to do some sessions on a thing Pete was producing. But he already had Kenney Jones. So that’s that. Kenney used to do the stuff when Moon was too drunk. But, with my playing, I think Ringo for some tunes, John Bonham for other tunes.

So you bring the techniques of other players or other drum styles into your playing?

Other styles, yeah. But there’s no point in me sounding like someone else.

There’s a Phil Collins style.

I guess. I’m far too close to it. I try to be versatile. There’s no point in me trying to sound like [jazz drummer] Jack DeJohnette when I play “Squonk”! Which is where Bill [Bruford] fell down. See, when Bill was in Genesis, he would not be anything other than Bill Bruford. I don’t pretend to be other people, but at the same time, I want to complement the song and do what’s best for the tune. So if it calls for just a straight (hums a 4/4 drum beat), that’s what I do. You don’t f**k about with it. And Bill wouldn’t do that. Chester [Thompson] will. Chester will play like he wants to play on certain tunes because that suits it. And on other things, for instance on “Afterglow,” he’ll play very, very straight.

That’s the mark of a true pro.

I think so. That’s why I like [drummer] Steve Gadd, for instance. He’ll play anything and everything and yet he’s not afraid to not play at all, if it makes sense. I think it’s a cliché now, but as you get a bit older and better at what you do, it’s what you leave out. Which is why [jazz keyboardist] Joe Zawinul’s music is fantastic.

Any other drummers?

Simon Phillips is a wonderful drummer, but believe me, I’ve seen him so many times, he’s obviously very influenced by [Billy] Cobham, and he used to take any opportunity to do incredible stuff, but not always in the right context. I used to do the same thing because when you like someone that much, you really do want to play like them. But you learn not to do it when it doesn’t call for it, even if you can. On Mike [Rutherford]’s album [Smallcreep’s Day], Simon played really, really well. He laid back. He does so many sessions now, that he just delivers what is necessary. I remember seeing Cobham with George Duke, and all he did was just constantly overplay. I think in the last few years, he’s actually calmed down a lot.

The Police have got a lot of space in their music. There’s plenty of room around Stewart Copeland.

He’s a very good drummer. He’s very original. But, I mean, that’s what it’s all down to.

Getting back to recording your album, it must have been nice to have a home studio.

Yeah. I’m a lucky boy, basically. I was lucky to get the people I got on my album. And it’s all very well to say, “I think it should be done this way or that way.” But not everybody can afford a studio in their own house.

That’s for sure!

“Studio” is a glamorous word for mine. It’s a room that used to be a master bedroom. There’s no control room. I admire how [Paul] McCartney did everything himself at home with his first solo album. [Steve] Winwood’s produced himself. And I reckon if he was in the room with us, he’d say that’s exactly what he wanted his music to sound like.

Did your album come out exactly the way you originally thought?

Yeah. If I had to change anything, there’s a track called “You Know What I Mean,” with piano, voice and strings. And if I had my way, I think maybe I’d have left the strings in. I was in two minds about doing it. I didn’t know which way to go. Tony [Smith], my manager, said, “I reckon it’s stronger emotionally without strings.”

Are you talking about keyboard strings?

No, these were real strings. It’s one of the reasons why I like it, because it sounded so nice. Real strings sound so lovely.

Still, doing your album at home is a great idea if you have the equipment and can get a competitive sound. I suppose you’re not inclined to do so much elaborate overdubbing though.

Peter [Gabriel] did that an awful lot on his album. There were a lot of tracks. Then they eliminated a lot to hear just the barest minimum but still suggesting the song. So just because I’ve got people on my album, doesn’t mean I used them everywhere they were playing. We even kept the drums off some places.

Are you still good friends with Gabriel?

Oh, yeah, I worked on his album, and I speak to him pretty regularly, because we’re in the same office. [Note: They shared a manager at the time.] He rang up to say he likes my album. He rings me up when he’s in town. Just a very sort of casual relationship. He’s a man of principle and he’s very stubborn. Sometimes he’s too stubborn for his own good, but he will get an idea and stick with it. Like the no cymbals idea for his third album. That was interesting. I said to him, “I agree with you, mate. Cymbals take up a lot of frequencies.” And I agree that it’s an interesting idea. But not on some things. And I’d love to play with cymbals, for instance on “I Don’t Remember.” That song could do with them. But he said, “Nope, I don’t want any metal on the album.” Sometimes he’s too dogmatic for his own good. But, I mean, I admire that he sticks to his guns.

How did mixing your album go without a “producer”? Did you and Hugh Padgham mix the album together?

Yes, and we had a good methodology. We did lots of very quick mixes. You don’t ever get the definitive mix when you work for 10 hours to get it. You do a quick mix the way you feel one day, and a week later you do another mix the way you felt that day. You get this whole bunch of mixes and, in the end, you just say, “I like that one.” That’s the best way to do it.

How would you keep track of mixes? When you’re mixing do they start to sound pretty similar?

Yeah, eventually. And at that point you think, “Well, OK, I passed it. The best mix was the first one.” That’s still your choice. But what happens with a band like Genesis is that you go through this period where there’s three people and the producer to please. And by the time you’ve gotten through that compromising situation, where you’ve got your little bit that you want in, you’ve gone through so many arguments, after a whole day of listening to the song, you’re dreading going back and doing it again. So that becomes the version of the song. For instance, we recorded “Squonk” on a particular day and that was the way it stayed. But now whenever we play it live, we all say, “Was it too fast or too slow?” referring to the version that we recorded that particular day in 1976.

Going out and playing on the road, you’re faithfully reproducing the recorded versions of your songs. But that’s what your audience wants to hear.

Right, but it’s only a version of a song. The reason why the Beatles’ stuff sounds so good is because they had to mix down from four-track. George Martin and them all reached the point with a backing track where it sounded great. Then they mixed that backing track out of necessity so they could add more. But you’ve got to maintain the spirit of the song. You can say, “Right, well, this is how we feel now. In two weeks’ time, we’ll come back to it, and hope we get the same feeling back.”

That takes a lot of planning. There’s an art to multi-tracking.

I find it easier with four-track and eight-track. I like the idea of just mixing down as you go along so you all reach this orgasmic moment, as it were, together. And that is the moment when it’s most potent. My eight-track demos sounded so good at that stage, out of necessity. I didn’t use anything that didn’t work because I didn’t have the tracks. Emitt Rhodes’ first album was recorded in his garage on his own. It was great! He wasn’t self-indulgent, showing how many instruments he could play. For him it was, this is what I want the bass to play.

Do you play bass?

I wish I could play bass! Sh*t, I do. I’m going to learn to play it before my next album, if I can. I mean, my piano playing is pretty limited. I didn’t know the rules, so therefore I didn’t know what rules I was breaking. So, you just sort of make nice noises on the thing. And that is something that could be the essence of what makes it attractive.

Watch Collins perform “In the Air Tonight” live in 2004

Collins’ solo recordings are available in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here. Genesis’ albums, including many expanded editions, are available here.

1 Comment so far

Jump into a conversationSo so cool! What a great interview!